The U.S. presidential candidates aren’t the only ones getting scrutinized by political fact-checkers. A growing number of state and local media watchdogs are keeping a close eye on the statements of politicians closer to home, too.

The Duke Reporters’ Lab global database of fact-checking ventures counts 34 active state and local fact-checkers across the country. These initiatives vet the accuracy of the people holding and seeking office in 22 states and the District of Columbia. That includes 18 of the 34 states electing senators in 2016, three of which — Missouri, New Hampshire and North Carolina — also happen to be holding some of the year’s closest governor’s races.

These state and local efforts represent more than two-thirds of the 47 active fact-checking efforts across the United States. The other 13 primarily focus on national politics. They include long-running sites and columns, such as FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, the Washington Post Fact Checker and the Associated Press, as well as the work of other big media companies that pay attention national political players, especially when there’s a presidential election.

But that scrutiny is increasing in down-ballot races too.

Here are a few trends worth noting among the state and local fact checkers, including some of the similarities and differences with those doing the same kind of work nationally and around the world:

The News Media’s Role

Most U.S. fact-checkers are professional journalists. All but two of the 34 state and local fact-checkers are affiliated with regional media organizations, including 18 that are linked to newspaper companies and 12 that are tied to local TV news stations.

The fact-checking team in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, is both — a joint project of the Gazette newspaper and local ABC affiliate KCRG-TV. And one site, PolitiFact Florida, involves two newspaper partners — the Miami Herald and PolitiFact’s owner, the Tampa Bay Times. Two others are tied to radio stations, and three are linked to digital news projects.

The leading role that newspapers, TV newsrooms and digital media outlets play in fact-checking is also true at the national level, but that is far less common outside the United States. About 60 percent of the international fact-checking initiatives the Reporters’ Lab tracks are stand-alone projects affiliated with or funded by civic non-profits and philanthropies focuses on government accountability.

In the United States, only two state and local fact-checkers are not connected to a news organization: Michigan Truth Squad, a reporting project that the non-profit Center for Michigan produces for its online journal; and the TruthBeTold.news, whose fact checks are part of a website staffed mainly by students in Howard University’s Department of Media, Journalism and Film in Washington, D.C.

At the national level, only three of 13 fact-checkers are not affiliated with other news companies: Verbatim, a project of the online encyclopedia Ballotpedia; FactCheck.org, which is based at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center; and Snopes.com, the independent debunking project launched by a husband-and-wife team 21 years ago.

Local Competition

Voters can now get analysis from multiple local fact-checkers in at least nine states — Arizona, California, Colorado, Iowa, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — all of which are holding U.S. Senate races this year.

In North Carolina, a presidential swing state where an incumbent Republican is up for re-election in both the governor and Senate race, the battle will likely be just as intense between the fact-checking teams at Raleigh’s WRAL-TV and its longtime newspaper rival, the News & Observer. But the local competition may be most intense in California, where politicians can expect scrutiny from three different news organizations: the Sacramento Bee, Voice of San Diego and Capital Public Radio in Sacramento.

PolitiFactication

The biggest player in the growth of state and local fact-checking is PolitiFact. After relying on newspapers for its initial partnerships, PolitiFact now has arrangements with local news sites, public radio and the E.W. Scripps TV chain.

Sacramento’s public radio station and the Raleigh-Durham newspaper are two of 18 local media partners that do state-level reporting under the PolitiFact banner. That’s more than half of the 33 U.S. state and local fact-checking initiatives.

In the past year, PolitiFact added 10 state affiliates to its roster, reviving its presence in Ohio and building new sites with partners in Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Nevada, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania.

PolitiFact’s push at the state level also helped drive the growing role of local TV news in the fact-checking business. Four of the nine new sites in its network are part of the partnership with the the Scripps stations, which the companies announced last October.

New local digital partners include BillyPenn in Pennsylvania and Reboot Illinois.

(Full disclosure: I used to work for the site’s parent company, which previously owned Congressional Quarterly and Governing magazine. Also, PolitiFact was founded by Bill Adair, a Duke media professor who still works for the site as a contributing editor and also oversees my work as co-director of the Reporters’ Lab. But PolitiFact’s effect on the numbers is impossible to ignore.)

Durability

A lot of fact-checkers are in it for the long haul — which is a good thing since politicians keep talking even after the voters have had their say.

Yes, if past election cycles are any indication, some local fact-checking initiatives will inevitably fold after Election Day, as will many of their counterparts in national media (the Reporters’ Lab database also includes a 12 inactive local fact-checkers in 11 states).

But nearly a third of the state and local fact-checkers in our database opened for business before the last presidential election in 2012.

One of the oldest, WISC-TV (News 3) in Madison, Wisconsin, has been at it for 12 years — longer than all but two of the national fact-checkers.

Implications

The growing role of TV newsrooms in the fact-checking movement is significant since political advertising is such a critical revenue source for local broadcasters. That means some owners are investing heavily in fact-checking projects that scrutinize one of their biggest revenue sources.

And since many politicians at the national level get their start running for office in down-ballot races, the growth of fact-checking at the state and local level could have long-term effects on political discourse. Perhaps local fact-checking will produce a generation of careful politicians who are already used to having to reporters examine every word they say long before they decide to seek national office. Or perhaps it will create a breeding ground for the kind of politicians who are most immune to intense media scrutiny.

Either way, fact-checking still seems to be a growing market.

Perhaps that’s why we should note that our tallies above do not count the work of U.S. fact-checkers at all levels, nationally and locally, who occasionally do fact-checking reports without establishing the kind of sustained, systematic effort the Reporters’ Lab database aims to track. But recent political history suggests at least a few more nascent and dormant fact-checkers across the country will spin up their efforts in the weeks ahead. When they do, we’ll be counting them — just as a growing number of voter will be counting on them.

Student researcher Hank Tucker contributed to this report. Here’s more information on how the Reporters’ Lab identifies the fact-checkers included in our global database and here’s a form you can use to tell us about a fact-checker we’ve overlooked.

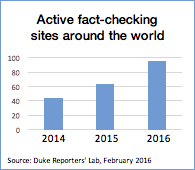

A bumper crop of new fact-checkers across the Western Hemisphere helped increase the ranks of journalists and government watchdogs who verify the accuracy of public statements and track political promises. The new sites include 14 in the United States, two in Canada as well as seven additional fact-checkers in Latin America.There also were new projects in 10 other countries, from North Africa to Central Europe to East Asia.

A bumper crop of new fact-checkers across the Western Hemisphere helped increase the ranks of journalists and government watchdogs who verify the accuracy of public statements and track political promises. The new sites include 14 in the United States, two in Canada as well as seven additional fact-checkers in Latin America.There also were new projects in 10 other countries, from North Africa to Central Europe to East Asia.