The number of active fact-checking projects around the world now stands at 156, with steady growth driven by expanding networks and new media partnerships that focus on holding public figures and organizations accountable for what they say.

And elections this year in the United States and around the globe mean that number will likely increase even more by the time the Duke Reporters’ Lab publishes its annual census early next year. Our map of the fact-checkers now shows them in 55 countries.

There were 149 active fact-checking ventures in the annual summary we published in February, up from 44 when we started this count in 2014. And after this summer’s Global Fact summit in Rome — where the attendee list topped 200 and the waitlist was more than three times as long — we still have plenty of other possible additions to vet and review in the coming weeks. So check back for updates.

Among the most recent additions is Faktiskt, a Swedish media partnership that aggregates reporting from five news organizations — two newspapers, two public broadcasters and a digital news service. We’ve seen other aggregation partnerships like this elsewhere, such as Faktenfinder in Germany and SNU FactCheck in South Korea. (This is a different model from the similarly named Faktisk partnership in Norway, where six news organizations operate a jointly funded fact-checking team whose work is made freely available as a public service to other media in the country.)

As we prepare for our annual fact-checking census, we plan to look more closely at the output of each contributor to these aggregation networks to see which of them we should also count as standalone fact-checkers. Our goal is to represent the full range of independent and journalistic fact-checking, including clusters of projects in particular countries and local regions, as well as ventures that find ways to operate across borders.

Along those lines, we also added checkmarks to our map for Africa Check‘s offices in Kenya and Nigeria. We had done the same previously for the South Africa-based project’s office in Senegal, which covers francophone countries in West Africa. The new additions have been around awhile too: The Kenya office has been in business since late 2016 and the Nigeria office opened two months later.

Meanwhile, our friends at Africa Check regularly help us identify other standalone fact-checking projects, including two more new additions to our database: Dubawa in Nigeria and ZimFact in Zimbabwe. The fast growth of fact-checking across Africa is one reason the International Fact-Checking Network’s sixth Global Fact summit will be in Cape Town next summer.

One legacy of these yearly summits is IFCN’s code of principles, and the code has established an independent evaluation process to certify that each of its signatories adheres to those ethical and journalistic standards. Our database includes all 58 signatories, including the U.S.-based (but Belgium-born) hoax-busting site Lead Stories; Maldita’s “Maldito Bulo” (or “Damned Hoax”) in Spain; and the “cek facta” section of the Indonesian digital news portal Liputan6. All three are among our latest additions.

There’s more to come from us. We plan to issue monthly updates as we try to keep our heads and arms around this fast-growing journalism movement. I’ll be relying heavily on Reporters’ Lab student researcher Daniela Flamini, who has just returned from a summer fact-checking internship at Chequeado in Argentina. Daniela takes over from recently graduated researcher Riley Griffin, who helped maintain our database for the past year.

Take a look at the criteria we use to select the fact-checkers we include in this database and let us know if you have any additions to suggest.

Comments closed

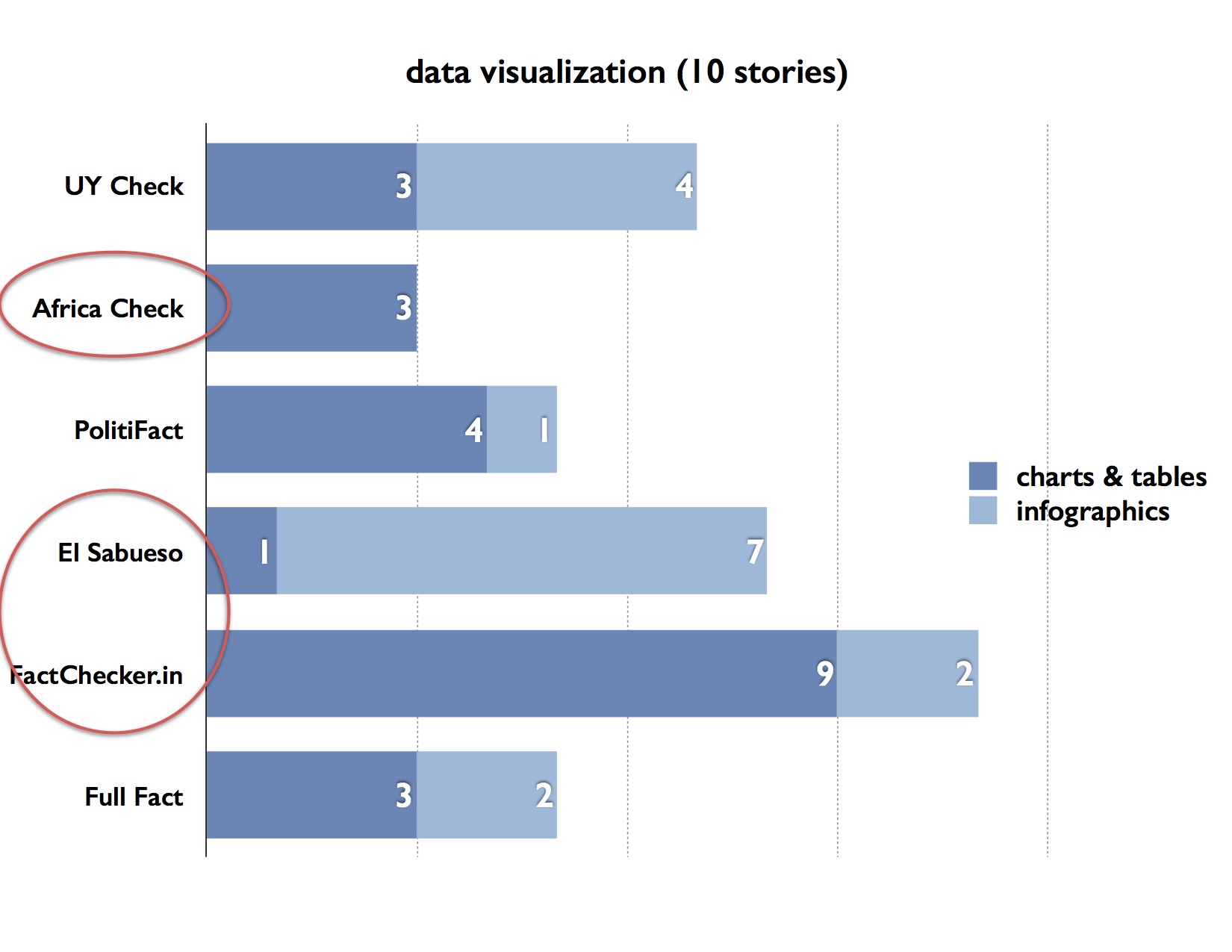

Graves and his researchers found a surprising range in the length of the fact-checking articles. UYCheck from Uruguay had the longest articles, with an average word count of 1,148, followed by Africa Check at 1,009 and PolitiFact at 983.

Graves and his researchers found a surprising range in the length of the fact-checking articles. UYCheck from Uruguay had the longest articles, with an average word count of 1,148, followed by Africa Check at 1,009 and PolitiFact at 983.