What do politically minded news junkies want from their election coverage? If they’re anything like NPR’s audience, they want fact-checking.

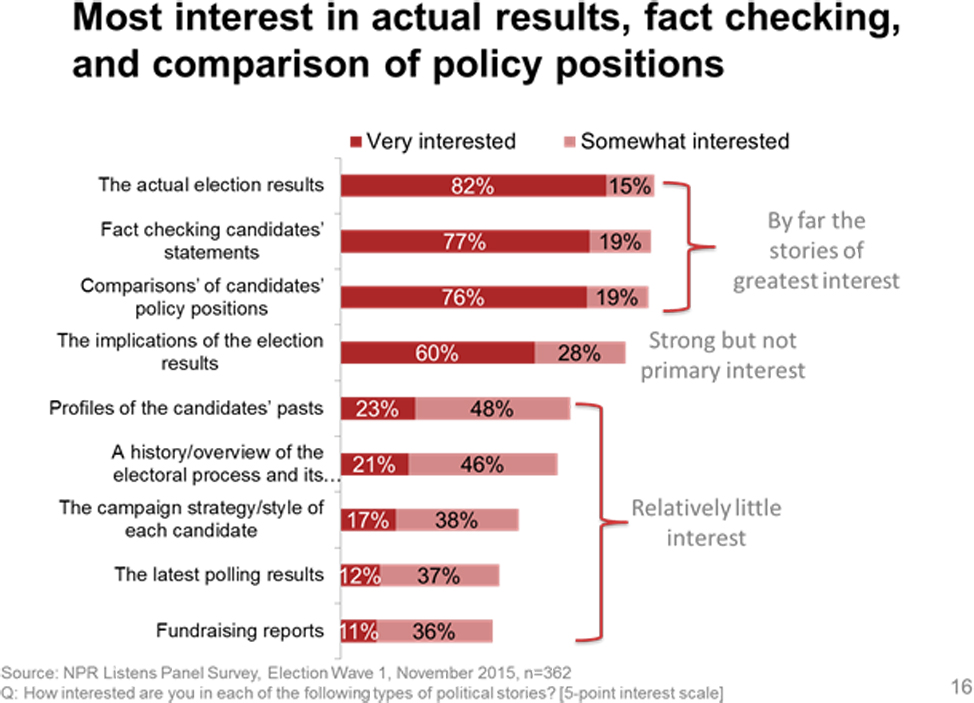

Last November, when the public radio company asked a sample of its audience about their interest in different kinds of political stories, 96 percent said they wanted stories that verified what the candidates said. Seventy-seven percent said they were very interested in fact-checks and 19 percent said they were somewhat interested.

But the survey has yet to translate into much on-air fact-checking, especially at the state and local level, where public media stations are hardly playing a leading role in the growing trend of checking politicians’ statements.

The Reporters’ Lab international database of fact-checkers currently counts more than 40 active projects in the United States. Of those, 14 are affiliated with radio or TV news companies. But only two are public broadcasters — PolitiFact California, which is run by Capital Public Radio in Sacramento, and NPR, which launched a new fact-checking feature called “Break It Down” last fall. A third, Minnesota Public Radio’s PoliGraph, has been inactive since June. Beyond public radio and public television, other non-profit media fact-checkers at the local level include Michigan Truth Squad from the Center for Michigan’s Bridge magazine and the digital news site Voice of San Diego.

The low public media numbers are surprising since NPR’s audience research found that few other political news stories resonated as much with its listeners as fact-checks do. Only actual election results did better in the survey, with 97 percent saying they cared about those stories, while 95 percent said they were most interested in reports comparing candidates’ positions.

By contrast, less than half of those who answered had much interest in the latest polls or fundraising reports — two staples of most political reporting diets.

The PowerPoint slide below breaks down the survey answers in more detail. The 362 people who answered were selected from a much larger pool of loyal NPR listeners — people from the network’s radio and digital audience who volunteer to provide feedback. My former colleagues at NPR, where I previously was managing editor for digital news, kindly shared the audience feedback with the Reporters’ Lab, which tracks the growth and impact of fact-checking.

The fact-checking numbers explain why NPR expanded its occasional fact-checking efforts for the 2016 election cycle. The numbers also reinforce the answers NPR heard four years ago, when it asked its audience a similar question and got a strikingly similar answer.

Yet even with such consistent interest, public broadcasters have taken a back seat to other media outlets in trying to verify political claims — a topic I discussed in an interview on a recent episode of The Pub, a weekly podcast about the public media business.

In truth, fact-checking is a tough beat for typical public media stations, especially those with limited reporting and editing staffs. The reporting process is time-consuming and intensive. And the results are likely to anger the most partisan elements of the audience. That’s no easy thing when you depend on listener and viewer donations and, in some communities, taxpayer support.

But there are upsides for local stations, too, including the ability to concentrate limited journalism resources on stories the audience says it eagerly wants. Fact-checks can also distinguish public broadcasters’ election in competitive media markets — unless the competition distinguishes itself first.

For now, commercial TV news outlets seem to be beating public broadcasters to those benefits. Nine of the active state and local fact-checking operations in the United States are affiliated with commercial TV stations. That includes four new PolitiFact state affiliates (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada and Ohio) that launched or relaunched in recent months as part of a partnership between the national fact-checker and the Scripps TV Station Group.

Commercial TV faces some of the same practical challenges that keep many public media outlets from taking on the truth beat. If anything, given the dependence on political advertising dollars at most commercial TV stations, you might even think those outlets would have far more to lose than public broadcasters. But the public broadcasters seem to be the ones who are losing out.

(As is only appropriate for an article about fact-checking, this post was updated shortly after it was published to correct two numbers: In NPR’s survey 77 percent said they were very interested in fact-checks and 19 percent said they were somewhat interested. Corrections always welcome here!)

Comments closed