Category: Fact-Checking News

Fact-Checking News

Global Fact 4: Notes from Day 2

A compilation of highlights from the annual gathering of fact-checkers around the world, taking place July 5-7 in Madrid

By Riley Griffin - July 7, 2017

The second day of Global Fact 4 kicked off with welcome remarks from Alexios Mantzarlis, director of the International Fact-Checking Network, Ana Pastor, anchorwoman for El Objetivo, and Bill Adair, director of the Duke Reporters’ Lab. Panels, Q&As, and breakout workshops took a deep dive into subjects ranging from automatic fact-checking to collaborative partnerships between media outlets. Highlights included Michelle Lee, who presented on the Washington Post’s latest project for fact-checking Donald Trump, and Wikimedia Foundation executive director Katherine Maher, who delivered a keynote speech about “the approximation of the truth.”

Each day, we’ll be collecting noteworthy moments from the summit, from social media interactions to memorable slides. Below are the highlights from Day 2 of the conference.

Tweet of the day

Fact-checkers of the world: stronger than ever! #GlobalFact4 pic.twitter.com/XD4cnCEW4H

— Farhad Souzanchi | فرهاد سوزنچی (@Farhadist) July 6, 2017

Farhad Souzanchi, the editor of Iran’s FactNameh, documented the crowd of 188 fact-checkers from 53 countries attending the plenary conference. Among the group were members from seven new fact-checking initiatives, based in such countries as South Korea and Norway.

Slide of the day

https://twitter.com/myhlee/status/882937457418932225

Full Fact, a nonprofit fact-checker in the United Kingdom, has partnered with Google to create innovative technologies for journalists. During a panel on automated fact-checking tools, Full Fact’s digital products manager, Mevan Babakar, explained the complex process of developing new fact-checking tools — like Trends and Robocheck — that identify viral disinformation and display pop-up fact-checks in real time. Referring to the slide, which illustrated the back end of an automated fact-checking tool, Babakar said, “This isn’t really sexy, but the products are.” Full Fact’s tools are still at the prototype stage, according to Babakar, but she anticipates they will one day be scalable across the industry.

Quote of the day

“At Wikipedia, we believe that an approximation of truth is all we can ever strive for.” — Katherine Maher, executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation

At the Wikimedia Foundation — the nonprofit organization that hosts Wikipedia — truth is an imperfect entity. The truth is malleable, biased, incomplete and ever-changing with the whims of history, executive director Katherine Maher said in her keynote speech. Although Maher does not consider herself a fact-checker, she believes in the pursuit of facts. During her speech, and in a Q&A with Poynter, Maher described how fact-checkers can take cues from Wikipedia when it comes to gaining readers’ trust and being as transparent as possible.

Global Fact 4: Notes from Day 1

A compilation of highlights from the annual gathering of fact-checkers around the world, taking place July 5-7 in Madrid

By Riley Griffin and Rebecca Iannucci - July 6, 2017

Global Fact 4, the annual gathering of fact-checkers around the world, is taking place July 5-7 in Madrid. Each day, we’ll be collecting noteworthy moments from the summit, from social media interactions to memorable slides. Below are the highlights from Day 1 of the conference.

Tweet of the day

And…we've started! #GlobalFact4 pic.twitter.com/o88yxIboW9

— International Fact-Checking Network (@factchecknet) July 5, 2017

The International Fact-Checking Network informally launched Global Fact 4 with a series of workshops about best practices for fact-checking, innovative tools and platforms for fact-checkers and the IFCN Code of Principles. Conference attendees can use #GlobalFact4 to contribute to the international dialogue surrounding fact-checking, fake news and freedom of the press.

Slide of the day

PolitiFact editor Angie Holan and Chequeado director Laura Zommer lectured 55 emerging fact-checkers on fundamental dos and don’ts of the practice during the Fact-Checking 101 workshop. For a claim to be checkable, Holan said it has to be feasible, factual and relevant, with enough evidence to deliver a verdict. Holan also said any claim based on an opinion does not meet those criteria — and journalists should avoid fact-checking them.

But it is not always that simple. Discerning factual claims from opinion is often difficult, Holan said. To illustrate her point, she brought up a statement from the National Republican Congressional Committee that sparked debate in the PolitiFact newsroom: “ISIS is infiltrating America and using Syrians to do it.” Was the claim checkable or not? Was it based on empirical evidence or opinion? Ultimately, PolitiFact determined there was sufficient empirical evidence to check the claim and come to a verdict: false.

Quote of the day

“Thanks to Donald Trump, ordinary Japanese people understand exactly what fake news is.” — John Middleton, co-founder of FactCheck Initiative Japan

The founders of FactCheck Initiative Japan spoke with the Reporters’ Lab about the need for fact-checking in a country where government influence and fake news are infecting public debate and news coverage. Middleton, a law professor at Hitotsubashi University, noted that misinformation had long existed in the Japanese media landscape, but the public did not take it seriously until Donald Trump was elected president of the United States.

FactCheck Initiative Japan is one of at least seven new fact-checking operations attending Global Fact for the first time.

At Global Fact 4: churros, courage and the need to expose propagandists

The next challenge for the Global Fact community: calling out governments and political actors that pretend to be fact-checkers.

By Bill Adair - July 6, 2017

My opening remarks at Global Fact 4, the fourth annual meeting of the world’s fact-checkers, organized by the International Fact-Checking Network and the Reporters’ Lab, held July 5-7, 2017 in Madrid, Spain.

It’s wonderful to be here in Madrid. I’ve been enjoying the city the last two days, which has made me think of a giant warehouse store we have in the United States called Costco.

Costco where you go when you want to buy 10 pounds of American Cheese or a 6-pound tub of potato salad. Costco also makes a delicious fried pastry called a “churro.” And because everything in Costco is big, the churros are about three feet long.

When I got to Madrid I was really glad to see that you have churros here, too! It’s wonderful to see that Costco is spreading its great cuisine around the world!

I’m pleased to be here with my colleagues from the Duke Reporters’ Lab — Mark Stencel, Rebecca Iannucci and Riley Griffin. We also have our Share the Facts team here – Chris Guess and Erica Ryan. We’ll be sampling the churros throughout the week!

It’s been an amazing year for fact-checking. In the U.K., Full Fact and Channel 4 mobilized for Brexit and last month’s parliamentary elections. In France, the First Draft coalition showed the power of collaborations during the elections there. In the United States, the new president and his administration drove record traffic to sites such as FactCheck.org and PolitiFact and the Washington Post Fact Checker — and that has continued since the election, a time when sites typically have lower traffic. The impeachments and political scandals in Brazil and South Korea also meant big audiences for fact-checkers in those countries. And we expect the upcoming elections in Germany, Norway and elsewhere will generate many opportunities for fact-checkers in those countries as well, just as we’ve seen in Turkey and Iran. The popular demand for fact-checking has never been stronger.

Fact-checking is now so well known that it is part of pop culture. Comedians cite our work to give their jokes credibility. On Saturday Night Live last fall, Australian actress Margot Robbie “fact-checked” her opening monologue when she was the guest host.

Some news organizations not only have their own dedicated fact-checking teams, they’re also incorporating fact-checks in their news stories, calling out falsehoods at the moment they are uttered. This is a marvelous development because it helps to debunk falsehoods before they can take root.

We’ve also seen tremendous progress in automation to spread fact-checking to new audiences. There are promising projects underway at Full Fact in Britain and at the University of Texas in Arlington and in our own lab at Duke, among many others. We’ll be talking a lot about these projects this week.

Perhaps the most important development in the past year is one that we started at last year’s Global Fact conference in Buenos Aires – the Code of Principles. We came up with some excellent principles that set standards for transparency and non-partisan work. As Alexios noted, Facebook is using the code to determine which organizations qualify to debunk fake news. I hope your site will abide by the code and become a signatory.

At Duke, Mark just finished our annual summer count of fact-checking. Mark and Alexios like to tease me that I can’t stop repeating this mantra: “Fact-checking keeps growing.”

But it’s become my mantra because it’s true: When we held our first Global Fact meeting in 2014 in London, our Reporters’ Lab database listed 48 fact-checking sites around the world. Our latest count shows 126 active projects in 49 countries.

I’m thrilled to see fact-checking sprouting in countries such as South Korea and Germany and Brazil. And I continue to be amazed at the courage of our colleagues who check claims in Turkey and Iran, which are not very welcoming to our unique kind of journalism.

As our movement grows, we face new challenges. Now that our work is so well-known and an established form of journalism, governments and political actors are calling themselves fact-checkers, using our approach to produce propaganda. We need to speak out against this and make sure people know that government propagandists are not fact-checkers.

We also need to work harder to reach audiences that have been reluctant to accept our work. At Duke we published a study that showed a stark partisan divide in the United States. We found liberal publications loved fact-checking and often cited it; conservative sites criticized it and often belittled it. We need to focus on this problem and find new ways to reach reluctant audiences.

I’m confident we can accomplish these things. Individually and together we’ve overcome great hurdles in the past few years. I look forward to a productive meeting and a great year. And I’m confident:

Fact-checking will keep growing.

Fact-checking booms as numbers grow by 20 percent

With fact-checkers gathering for annual Global Fact summit, a Reporters’ Lab tally finds 17 new projects around the world. (But still not in Antarctica.)

By Mark Stencel - June 30, 2017

The 200-person attendee list for next week’s Global Fact 4 summit in Madrid is up 80 from last year’s meeting in Buenos Aires, and more than twice what it was in London two years ago. And with good reason: The number of fact-checkers has been growing too, driven by concerns about a global epidemic of misinformation, viral hoaxes and official lying.

The Duke Reporters’ Lab database of international fact-checking initiatives now counts 126 active projects in 49 countries. That’s up 20 percent from the 105 projects we tallied a year ago. And that year-over-year increase continues the growth we found in for our most recent annual fact-checking census in February.

Active Fact-Checkers by Continent

Africa: 4

Asia: 14

Australia: 2

Europe: 46

North America: 47

South America: 13

NOTE: All the numbers presented throughout this article are as of June 30, 2017. An updated map, global tally and country-by-country lists are available on the Reporters’ Lab fact-checking page.

It’s great to see so many new sites: 17 of the 126 fact-checkers opened for business in the past 12 months. One of the newest, the Ferret Fact Service in Edinburgh, launched just nine weeks ago. And there was the welcome return of Australia’s ABC. Government funding cuts ended that project last year, but it returned from an 11-month hiatus on June 5 as a jointly branded partnership of the public broadcasting company and RMIT University in Melbourne. And the same Toronto-based team of technology activists that built a site four years ago to track Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s campaign promises launched a new fact-checking service in April: Fact-Nameh (“The Book of Facts”), the PolitiFact of Iran.

Of the fact-checkers that launched in the past year, seven were in Europe, four were in North America, three were in Asia and three were in South America. And all appeared in countries with roiling political situations plagued by false claims and misinformation that made global headlines — from presidential impeachments (Brazil and South Korea) to an attempted coup (Turkey) to intense immigration fights (everywhere!) to nationwide campaigns and voting (South Korea and Turkey again, plus Austria, Iran, Italy, Kosovo, the U.K and, um, the U.S. — with Germany’s turn coming in September).

If ever there was a time for fact-checking, this was it.

The United States is home to a third (42) of the fact-checkers we track. We also found that 16 other countries have at least two fact-checking projects, and seven of those have three or more, including Brazil (8), the United Kingdom (6), France (5), South Korea (5), Ukraine (4) and Canada (3).

We saw an encouraging sign about quality: One-fifth of the fact-checkers in the database (25 of the 126) are already verified signatories of International Fact-Checking Network’s newly established Code of Principles. And that number will grow because independent evaluators are reviewing additional applications. The code was written by an IFCN committee last summer to encourage best practices such as fairness, a commitment to correcting errors, and transparency on sources, methodology and funding. Facebook is using IFCN’s Code to identify trustworthy non-partisan fact-checking partners to help flag fake news and other misinformation.

Most of the sites, about six out of 10, are affiliated with established news media organizations. The rest are a mix of independent journalism and research projects, many of which are affiliated with universities, think tanks and non-governmental groups instead of existing media companies.

The ties to media companies are especially common in the United States, where 83 percent of fact-checkers (35 of 42) are operated by or closely affiliated with bigger news organizations. In the rest of the world, a bit over half (44 of 84, or 52 percent) have direct news media ties. But that mix may be shifting. In our 2016 census, less than half of the fact-checkers outside the U.S. were part of a larger media house (24 of 55, or 44 percent).

If you’re keeping track of all these numbers, you better write them down in pencil and be ready for updates. We still have a pending list of other fact-checkers we need to evaluate, including some whose staff we look forward to meeting at the Madrid summit. (Here’s an explanation of how the Reporters’ Lab identifies the fact-checkers we include in our database. In addition to journalism that fairly examines the accuracy of statements by public figures and institutions, we also look for authoritative, nonpartisan reporting on the progress of political promises and the credibility of widely shared online sources of information and misinformation.)

The healthy growth we’ve measured since last year’s Global Fact conference comes even after we had to move more than a dozen other fact-checkers to inactive status. In fact, at this point we have a list of more than five dozen inactive fact-checking initiatives.

That kind of fluctuation and turnover is consistent with the natural attrition we’ve tracked over the past several years — with many fact-checkers springing up for campaigns and then going dark. Some election-oriented fact-checkers will reliably return for the next campaign. That requires us to continuously determine which projects are hibernating comfortably and which have met their ultimate fact-checking fate. But since we can now base those choices on several years of observation, we now leave these seasonal fact-checkers marked as “active” in our database, noting their campaign focus in our descriptions. And we are continuously finding established fact-checkers who previously escaped our notice, which also adds to the growing tally. If you’re one of them, please let us know.

The Reporters’ Lab is a project of the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy at Duke University’s Sanford School for Public Policy. We started the fact-checking database three years ago to track the reach and impact of this journalism. It also supports the Lab’s efforts to develop tools and services that help fact-checkers report and disseminate their work to a bigger audience. That includes Share the Facts, a project that helps fact-checkers distribute their reporting on other websites and platforms, including devices such as the Amazon Echo. Google also has used the Lab’s fact-checking database in its recent efforts to elevate fact-checks in search results and on the redesigned Google News page.

This update is based on research compiled over several months in part by Reporters’ Lab student researcher Hank Tucker. Alexios Mantzarlis of the Poynter Institute’s International Fact-Checking Network also contributed, as did Reporters’ Lab director Bill Adair, Knight Professor for the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke University (and founder of PolitiFact). Thanks also to Cristina Tardáguila of Agência Lupa in Brazil, Itziar Bernaola of El Objetivo in Spain, Boyoung Lim of Newstapa in South Korea, and many other fact-checkers around the world who help us keep up with this fast-growing form of journalism.

Please send updates and additions to Reporters’ Lab co-director Mark Stencel (mark.stencel@duke.edu).

Heroes or hacks: The partisan divide over fact-checking

We analyzed nearly 800 references to fact-checking and found a stark divide. Liberal writers like fact-checking; conservatives don't.

By Bill Adair and Rebecca Iannucci - June 7, 2017

Conservative writers aren’t fond of fact-checking. They belittle it and complain that it’s biased. They say it’s “left-leaning” and use sarcastic quotes (“fact-checking”) to suggest it’s not legitimate. One writer likens PolitiFact to a Bangkok prostitute.

Liberal writers admire fact-checking. They cite it favorably and use positive adjectives such as “independent” and “nonpartisan.” They refer to fact-checkers as “watchdogs” and “heroes.”

To examine partisan differences over fact-checking, we analyzed some of the most widely read conservative and liberal sites. Our students in the Duke Reporters’ Lab identified 792 statements that referred to fact-checkers or their work. We found a stark partisan divide in the tone, the type of references and even the adjectives the writers used.

Our report, Heroes or hacks: The partisan divide over fact-checking, reveals a serious problem for the growing number of fact-checkers, journalists who research and rate the accuracy of political statements. They emphasize their neutrality and nonpartisan approach, but they face relentless criticism from the political right that says they are biased and incompetent.

Our analysis found:

- Liberal websites were far more likely to cite fact-checks to make their points than conservative sites were.

- Conservative sites were much more likely to criticize fact-checks and to allege partisan bias.

- When our student researchers categorized the tone of mentions, we found liberal sites made most of the positive references, while the negative references came primarily from the right.

- Conservative sites made the most critical comments about fact-checking, occasionally using quotation marks (“fact-checking”) to imply it wasn’t legitimate.

(Read the full report.)

We found the most revealing differences in the words the writers used to describe fact-checkers and their work.

Liberals emphasize they are nonpartisan and call them “respected,” “reputable” and “independent.” Fact-checkers are “watchdogs” or “heroes.” PolitiFact is described as “Pulitzer Prize-winning.”

Conservatives use words such as “left-leaning,” “biased,” “hackiest” and “serial-lying.” They question the legitimacy of fact-checkers by calling them “self-proclaimed.”

The most wicked criticism came from Jonah Goldberg of the National Review, who called PolitiFact “the hackiest and most biased of the fact-checking outfits, which bends over like a Bangkok hooker to defend Democrats.”

Our findings indicate that fact-checkers have some work to do. They need to strengthen their outreach to conservative journalists and, particularly, to conservative audiences. The fact-checkers need to understand the reasons for the partisan divide and find ways to broaden the acceptance of their work.

International fact-checking gains ground, Duke census finds

Number of projects up 19% in a year; U.S. count holds steady after tumultuous election season

By Mark Stencel - February 28, 2017

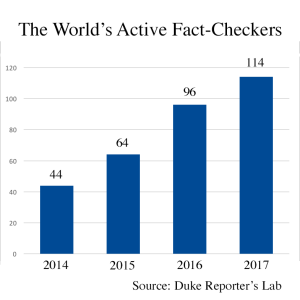

Falsehoods and “fake news” are keeping journalists and researchers busy in 47 countries, where 114 dedicated fact-checking teams are now calling out public figures for inaccuracies.

The number of active fact-checking projects increased more than two and half times since the Duke Reporters’ Lab began its annual census three years ago. The current count is up 19 percent from 2016, when the number of active fact-checkers was 96.

was 96.

Nineteen of the fact-checkers started in 2016. That includes 10 in the United States, seven of which focused on state and local politics. The number of startups increases to 23 if we include four additional U.S. fact-checkers that launched in 2016 to cover the U.S. elections but have since shut down. Those four are now among the 55 inactive fact-checking projects that are also tracked by the Reporters’ Lab.

Also among those inactive projects is the ABC News Fact Check in Australia, which closed down in June after government budget cuts. But the ABC Fact Check is expected to return as soon as next month as part of a new partnership between the public broadcaster and RMIT University’s School of Media and Communication — a phoenix-like cycle that we’ve seen before among the world’s fact-checkers.

The Lab regularly updates the database of fact-checkers, which peaked last year at 121 before the end of the raucous U.S. election season (see the current MAP AND LIST). By the time American voters went to the polls, the number of U.S. fact-checkers had temporarily surged to 53 — up from 41 during the presidential primary campaign a year ago — with most focused on politics at the state and local level.

But with the shuttering of eight of PolitiFact’s state affiliates since the election and other updates to our list, the U.S. year-over-year count grew by just two to 43 — or about 38 percent percent of the global total. [UPDATE, March 25: PolitiFact Georgia resumed operations after brief hiatus in March 2017. PolitiFact’s reporting about Georgia politics is now syndicated to state news outlets, including The Atlanta Journal Constitution. The newspaper previously produced its own fact checks, using PolitiFact’s platform and methodology from 2010 to 2016. The numbers of fact-checkers referred to throughout this article are still based on our February count.]

The post-election dip in the U.S. was not surprising. Media fact-checkers that come to life in campaign years often go offline or close down completely after the votes are tallied — a trend PolitiFact founder Bill Adair lamented in an Election Day commentary for the New York Times.

“[P]oliticians don’t stop lying on Election Day,” wrote Adair, who now teaches journalism at Duke and oversees the university’s Reporters’ Lab.

Meanwhile, the fact-checking movement has continued to grow internationally.

Including the United States, 11 countries have more than one fact checker:

United States: 43

France: 6

United Kingdom: 6

Spain: 4

Ukraine: 4

South Korea: 3

Canada: 3

Brazil: 3

Mexico: 2

Argentina: 2

Colombia: 2

Growth was especially strong in Europe, where our count increased 44 percent — from 27 in 2016 to 39 now. While some of that increase came from adding established fact-checkers we previously hadn’t identified, seven of the European fact-checkers were among the 2016 startups.

Among the operations that opened for business in 2016 were fact-checkers in Ireland, Kosovo, Lithuania, Spain and the United Kingdom, plus two in Ukraine (some of these launched early enough to in the year to be counted in last February’s report). New fact-checkers in Columbia and Kenya also launched in 2016. And with upcoming elections in France, Germany and elsewhere, we expect global growth in fact-checking will continue in 2017.

FACT CHECKERS BY CONTINENT

Africa: 5

Asia: 9

Australia: 1

Europe: 39

North America: 50

South America: 10

In the United States, fact-checkers are often part of an established news organization. But elsewhere in the world, they are less likely to have a media affiliation.

While more than 80 percent of the U.S. fact-checkers (36 of 43) are part of a media company, fewer than half in the rest of the world (33 of 71) have those kinds of direct ties. The others are mainly affiliated with universities and other non-governmental organizations that focus on issues such as civic engagement, government transparency and public accountability. Still, those independent fact-checkers frequently establish business or distribution relationships with news organizations to help pay for their work and expand their audiences.

The Reporters’ Lab is a project of the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy at Duke University’s Sanford School for Public Policy. The Lab’s staff and student researchers identify and evaluate fact-checkers that specifically focus on the accuracy of statements by public figures and institutions in ways that are fair, nonpartisan and transparent. The Lab also gets guidance from the Poynter Institute’s International Fact-Checking Network, which established a Code of Principles in 2016.

Student researcher Hank Tucker contributed to this report, as did Reporters’ Lab director Bill Adair, Knight Professor for the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke University and founder of PolitiFact. Please send updates and additions to Reporters’ Lab co-director Mark Stencel (mark.stencel@duke.edu).

[VIDEO] Reporters’ Lab students test Share the Facts skill on Amazon Echo

Student researchers asked "Alexa" about numerous fact-checks, in order to help improve her accuracy and comprehension

By Rebecca Iannucci - February 27, 2017

If you walked into the Reporters’ Lab in the last few weeks, you heard a lot of questions for Alexa.

“Alexa, ask the fact-checkers: Is it true that there was widespread voter fraud in the 2016 election?… Is it true that Donald Trump said climate change was a hoax?… Do schools really have guns to protect students from bears?”

Student researchers in the lab have been peppering our Amazon Echo with questions – some serious and some absurd – as part of a user testing project for our Share the Facts skill for the Echo.

Share the Facts is the first fact-checking app for the Echo. When you enable it on your Echo, Alexa responds to queries with summaries from the Washington Post, PolitiFact, FactCheck.org and GossipCop, a Hollywood fact-checker, among others. We’ve been conducting the tests to improve the likelihood the Echo will match a query with a published fact-check. Our students tested more than 100 new queries on Alexa so we can better understand the reasons behind her hits and misses.

Check out the video below for a sample of the students’ tests:

Our tests found hits and misses. For example, a question about the fictional Bowling Green Massacre was answered with a fact-check about Kellyanne Conway’s false statements on the subject.

But when asked if Donald Trump’s inauguration was really the most watched ever, Alexa replied, “GossipCop rated it Zero when HollywoodLife said Kanye West is performing at Donald Trump’s inauguration.” (Uh, okay…)

Overall, though, the user testing served an important purpose: to better understand and improve how Share the Facts is used, in order to provide more immediate and accurate fact-checks to a curious audience.

Want to test FactPopUp? Here’s how to install and use the fact-checking tool

During Tuesday's speech, Google Chrome users will have another opportunity to experiment with our real-time fact-checking tool

By Gautam Hathi - February 23, 2017

UPDATE. 10 a.m. Feb. 28: We’ve discovered that some users get a black window when they should be seeing a photo of Trump on the livestream page. If that happens to you, close all your Chrome windows and relaunch Chrome. Email us at factpopup@gmail.com if you have problems and we’ll troubleshoot.

On Tuesday, Feb. 28, the Duke Reporters’ Lab will conduct another test of FactPopUp, our real-time fact-checking tool, during President Trump’s address to a joint session of Congress. The free Chrome extension will provide users with a livestream of the event, along with occasional pop-up notifications of fact-checks from PolitiFact, which will be checking Trump’s statements live.

Previous tests of FactPopUp have been encouraging, with more than 500 people successfully using the tool to receive fact-checks during the third presidential debate and President Trump’s inauguration.

If you would like to be a part of this test, here are a few simple steps to follow.

1. Go here and click the “Add to Chrome” button.

2. Click the “Add extension” button on the prompt that comes up.

3. Click the “Open live stream” button in the page that opens after the extension installs. This should open a web page with a full-screen livestream of the event.

4. If you have to close the stream window before the event, click on the FactPopUp icon to the right of your Chrome address bar and then click “Open live stream”:

5. If the FactPopUp icon doesn’t show up next to the address bar, find it in the Chrome menu.

If you take part, we’d love to hear your feedback. Send your comments and/or questions to factpopup@gmail.com.

Improved version of FactPopUp, our real-time fact-checking tool, now available

The Chrome extension, which fact-checks political events as they happen, is now more reliable and easier to use

By Gautam Hathi - January 26, 2017

We’ve made some improvements to FactPopUp, our real-time fact-checking tool.

FactPopUp allows fact-checking organizations to provide live fact-checks via Twitter to users watching a live stream of a political event on their computers.

The new version is more reliable and easier to use. A Twitter account is no longer required to use the extension, and FactPopUp can be easily configured to receive fact-check tweets from any Twitter account.

Powering the new version of FactPopUp is a significantly revised architecture. Users still download a simple Chrome extension from the Chrome webstore. However, fact-checking organizations will now run a simple server which uses Azure Notification Hubs to check for new tweets and send them to the extension clients.

The new version of FactPopUp was successfully tested by PolitiFact in order to provide live fact-checking for the presidential inauguration. More than 500 people have now participated in tests of FactPopUp, both during the inauguration and the 2016 election debates.

The code for the new version of FactPopUp is now available on GitHub, allowing anyone to set up and experiment with their own version of the system. In addition, FactPopUp is now configured so that the Reporters’ Lab can explore working with a range of fact-checking organizations to leverage FactPopUp for use during major political events around the world.

The Reporters’ Lab will continue to test and iterate FactPopUp, with the goal of eventually creating a universal live fact-checking solution that works on all major platforms and for all political events.

Fact-checkers’ reach keeps growing around the globe

We’ve updated our map to make it easier to navigate 10 dozen active sites and projects the Reporters’ Lab is monitoring around the world.

By Mark Stencel - November 22, 2016

The 2016 U.S. election has involved a slew of misstatements from both presidential candidates, with no shortage of Pinocchios, “whoppers,” flip-flops and other “lowlights.” And that will certainly continue long after the ballots are officially counted.

More than 50 fact-checkers across the United States helped voters sort facts from fibs in this campaign year. With 2017 looking like another big year for truthiness and misstatements, the Duke Reporters’ Lab is rolling out some improvements on the global map we use to track this important journalism.

Based on our current count, fact-checkers are already on the job in at least 10 countries where voters will be casting ballots in the coming year, including Argentina, Chile, Czech Republic, France, India, Kenya, Netherlands, Senegal, Serbia and South Korea.

Overall, we currently count 119 active fact-checkers in 44 countries. And there are multiple fact-checkers working in 12 countries.

Because fact-checking is concentrated in many cities, making the checkmarks on our map overlap, we’ve added a clustering feature that will help users find and navigate the places where we have listed multiple teams.

The map now distinguishes the active fact-checkers (shown with red pins) from the more than 40 others that have closed for one reason or another (they’re indicated by gray pins). The map also has an up-to-date tally of both the active and inactive projects. You can click on that box to look at one category or the other.

Country-by-country lists, including a tally of active projects, are available with the “Browse in List” link (find it to the right of the map).

We regularly add new fact-checkers and review the status of older ones, so our tally sometimes goes up and down. We know from past years that some U.S. fact-checkers will close for the “off-season” and the same is true in other countries.

We’re always on the lookout for fact-checkers, including those that look at issues other than politics. One example is New York-based Gossip Cop — a recent addition to our database that’s been debunking celebrity rumors since 2009.

Other recent additions include US. fact-checkers at the Cincinnati Enquirer in Ohio and the University of Wisconsin in Madison. We also added or reactivated four others that came out of hibernation for the election.

International additions include established projects in Denmark, France and Japan, and newer initiatives in Kenya and Lithuania.

If you see a fact-checking venture we’re missing, please let us know: mark.stencel@duke.edu