Category: Fact-Checking News

Fact-Checking News

2025 census: Fact-checkers persevere as politicians, platforms turn up heat

The number of fact-checking projects has remained roughly consistent in recent years, with a slight decrease so far in 2025

By Erica Ryan - June 19, 2025

By the numbers:

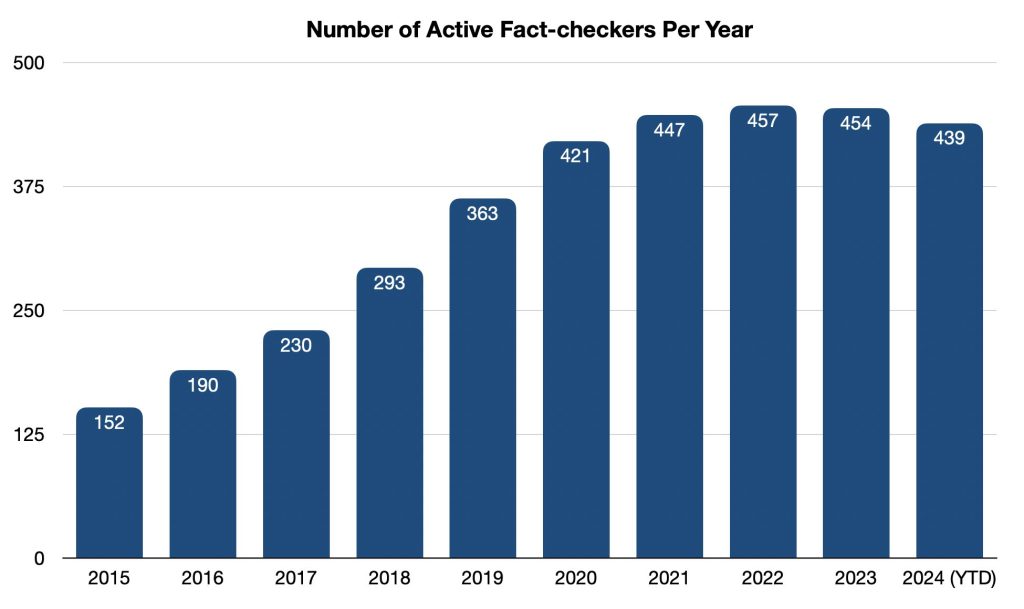

- The Duke Reporters’ Lab counts 443 active fact-checking projects around the world in 2025, down about 2 percent so far from last year. However, the number of projects has remained largely consistent in recent years, hovering around 450.

- The slight decline comes as social media giant Meta, which partners with fact-checkers to issue independent rulings on misinformation, ended that program in the U.S.

- The volume of fact-check articles this year decreased by about 6 percent compared with 2024, based on our tally of ClaimReview, a tagging system used by many fact-checking organizations.

- Fact-checkers are still active in 116 countries and in more than 70 languages. Nearly 80 fact-checking projects operate in countries judged particularly dangerous for journalism by Reporters Without Borders.

- Even in the U.S., where Meta has stopped its partnerships, new fact-checkers continue to spring up. One nationwide effort has signed up three new local newsrooms this year and has plans for four more in the near future.

After years of weeding through the ever-growing tangle of misinformation, journalists and researchers who call out falsehoods were dealt a blow in 2025 that could reshape the landscape of fact-checking around the world.

In January, just before President Donald Trump was inaugurated for a second time, Meta announced an end to its fact-checking program in the U.S., which paid professionals to issue independent rulings on potential misinformation posted on its platforms, including Facebook and Instagram. Fact-checkers around the world feared the move could lead to similar cutbacks elsewhere.

But despite the fallout of the U.S. decision, which has created a difficult environment for raising money from foundations and other big donors, there has yet to be a dramatic decline. In its annual census, the Duke Reporters’ Lab counts 443 active fact-checking projects, down about 2 percent so far from the 451 active at the end of 2024. And new projects on the horizon, including newsrooms slated to join the Gigafact fact-checking effort in the U.S., could nudge the final count upward for the year.

Overall, the net number of fact-checking projects around the globe has remained largely consistent in recent years, even as social media platforms have shifted toward less content moderation in the wake of billionaire Elon Musk acquiring Twitter in 2022.

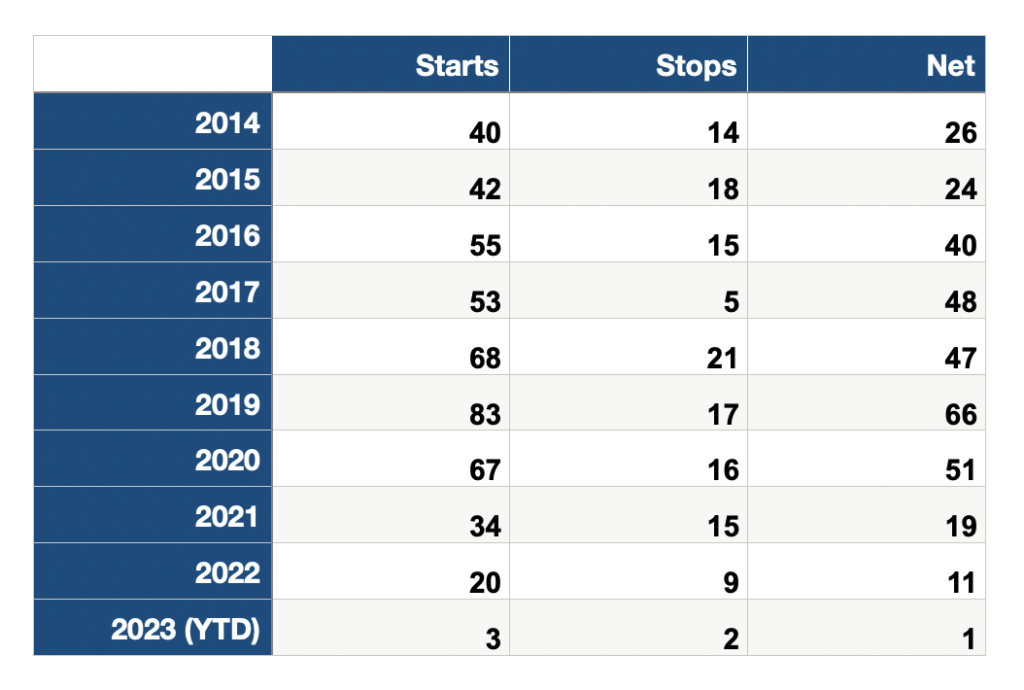

As happens every year, they come and go. In 2024, 13 projects got their start and 13 ended, making a net of zero, and in 2023, 17 opened their doors and 19 closed, a decrease of 2.

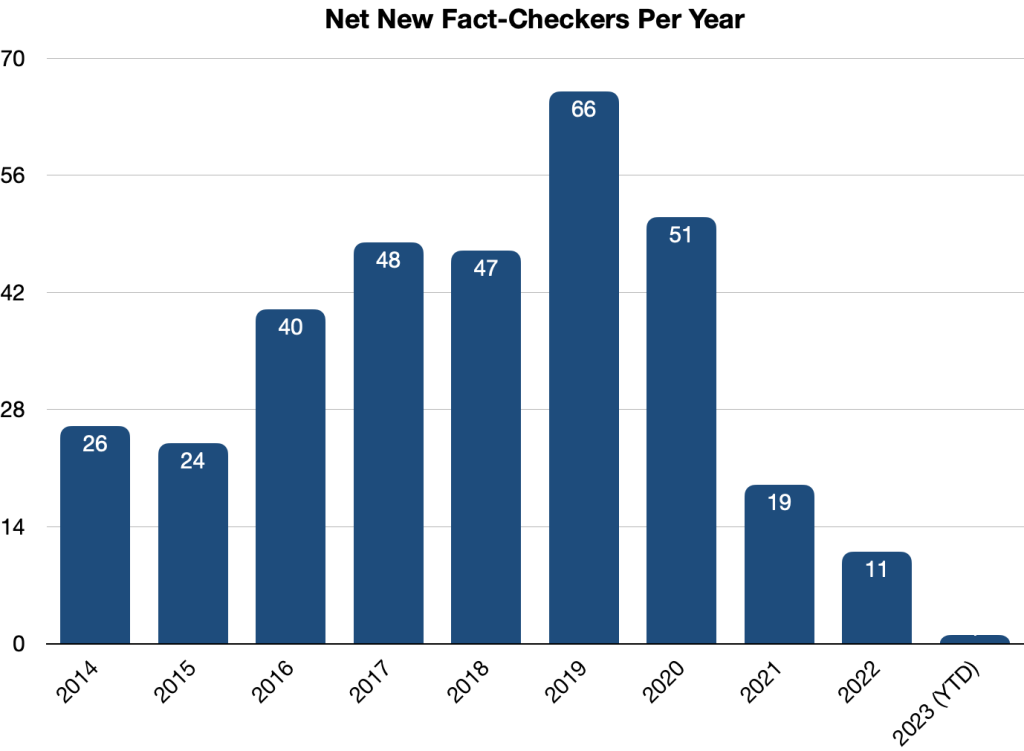

Still, the boom years seem to be over. The relative stability in the overall number of projects follows many years of massive growth in the industry. When the Reporters’ Lab first started tracking more than a decade ago, each year brought dozens of new fact-checkers, with the total number of projects shooting up from 110 in 2014 to 453 by the end of 2022, an increase of more than 300 percent.

But so far in 2025, fact-checking has seen a slight decline.

In February, the American broadcast group Tegna ended its centralized VERIFY initiative, putting a message on its website directing users to visit their local Tegna stations for VERIFY content. In April, conservative publication The Daily Caller also stopped updating its Check Your Fact initiative.

But another well-known conservative site, The Dispatch, vowed to continue, despite the end to Meta’s fact-checking program in the U.S.

“[We] did not get into the fact-checking business because of Meta’s program, or because we thought it would make us a lot of money. We got into the fact-checking business because we think it’s important,” wrote CEO and editor Steve Hayes. “…We’re not under any illusion that our decision to continue our fact-checking operation is going to save American democracy or the journalism industry. But we’re going to keep doing it because the truth matters, even if some of the loudest and most powerful voices in politics, business, and media are trying to tell you it doesn’t.”

The slight decline in fact-checking so far in 2025 is also reflected in the number of articles being produced. In the first five months of 2024, about 40,500 articles were tagged with ClaimReview, a system to identify fact-checks in search results and apps that is used by many of the world’s fact-checking organizations. During that same period this year, that number was down to about 38,000.

The future of funding

Meta’s decision to end its third-party fact-checking program in the U.S. (and replace it with a user-driven system like X’s Community Notes) has sparked concerns that the company would do the same thing in the rest of the world.

That would have a devastating impact on fact-checking organizations that have become reliant on the company for financial support. Nearly 160 projects from our count were listed as participating in Meta’s fact-checking program in early 2025 — about a third of the active projects around the world.

The percentage was higher among signatories to the International Fact-Checking Network’s Code of Principles, which holds fact-checkers to standards of nonpartisanship and transparency.

In an IFCN survey released in March, almost two-thirds of respondents reported participating, and on average, those organizations reported receiving about 45 percent of their revenue from Meta last year.

Forging ahead

Overall, our numbers show fact-checkers remain active in 116 countries and more than 70 languages.

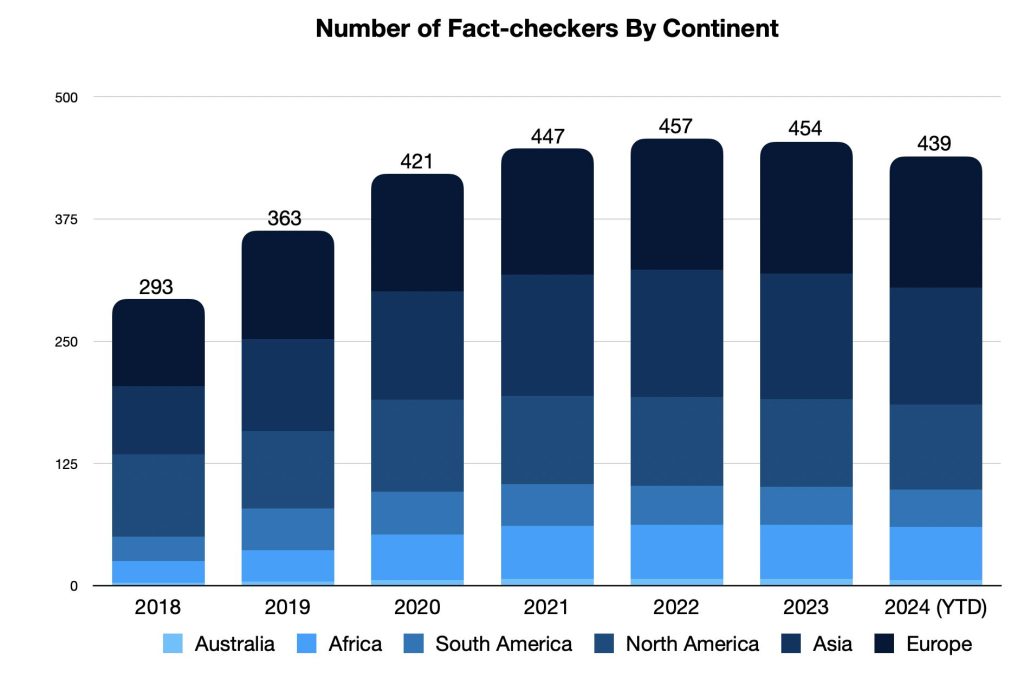

While Asia has seen slight declines each year since 2022, the number of projects continued to inch up for longer in Europe, which had an increase from 131 at the end of 2022 to 139 by the end of 2024. The number of projects held almost steady during that time frame in Africa (with 66-67 projects) and South America (with 38-39).

Many fact-checkers are continuing to do their work in hostile environments.

About 80 of the world’s active fact-checking organizations operate in countries that have been judged by Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index to be particularly dangerous for practicing journalism. Those places include India, Hong Kong, Bangladesh and Egypt, all of which have multiple fact-checking projects. There are also lone fact-checking outposts in countries like Iran, Cuba, Saudi Arabia and Cambodia.

And even though Meta has backed away from funding fact-checking in the U.S., new operations continue to spring up.

Three newsrooms — Maine Trust for Local News, South Dakota News Watch and Suncoast Searchlight in Florida — have all begun participating this year in the Gigafact project, an effort that helps local journalists produce bite-sized “fact briefs” that give yes or no answers about factual claims.

That brings Gigafact’s network to more than a dozen newsrooms across the country — and it expects to add four more local news organizations to its roster in June.

About the Reporters’ Lab and its Census

The Duke Reporters’ Lab began tracking the international fact-checking community in 2014, when director Bill Adair organized a group of about 50 people who gathered in London for what became the first Global Fact meeting. Subsequent Global Facts led to the creation of the International Fact-Checking Network and its Code of Principles.

The Reporters’ Lab and the IFCN use similar criteria to keep track of fact-checkers, but use somewhat different methods and metrics. Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database and census reports. If you have questions, updates or additions, please contact Erica Ryan.

Previous Fact-Checking Census Reports

Note: The Reporters’ Lab regularly updates our counts as we identify and add new sites to our fact-checking database. As a result, numbers from earlier census reports differ from year to year.

- April 2014

- January 2015

- February 2016

- February 2017

- February 2018

- June 2019

- June 2020

- June 2021

- June 2022

- June 2023

- June 2024

Locking up misinfo in the Reporters’ Lab vault

New tool quarantines fact-checked social media posts for journalists

By Erica Ryan - December 3, 2024

Fact-checkers around the world now have access to a new tool from the Duke Reporters’ Lab that allows them to save and link to social media posts that have been fact-checked, without boosting traffic to the original creator.

The new feature is part of MediaVault, an archiving platform created by the Reporters’ Lab with support from the Google News Initiative, and it was developed in response to feedback from fact-checkers. In addition to being able to save the social media posts they were fact-checking, journalists said they wanted to be able to link to the content without amplifying it.

Public-facing links are now generated for all social media posts archived in MediaVault, and those links can be used in fact-check articles.

Not only does the tool allow fact-checkers to avoid boosting views for creators of misinformation, it also preserves long-term access to the content. That means there will still be a record of exactly what a post claimed, even if its creator deletes it or the social media platform removes it.

Since the Reporters Lab announced the new feature in late October, MediaVault has seen a significant boost in users, with more than 200 new sign-ups.

Being able to archive social media posts is a problem the fact-checkers at India Today have been struggling with for a long time, says Bal Krishna, who leads the fact-checking team at the news organization. “This is just amazing,” he says of MediaVault.

MediaVault is free for use by fact-checkers, journalists and others working to debunk misinformation shared online, but registration is required.

Researchers mine Fact-Check Insights data to explore many facets of misinfo

The dataset from the Duke Reporters’ Lab has been downloaded hundreds of times

By Erica Ryan - June 20, 2024

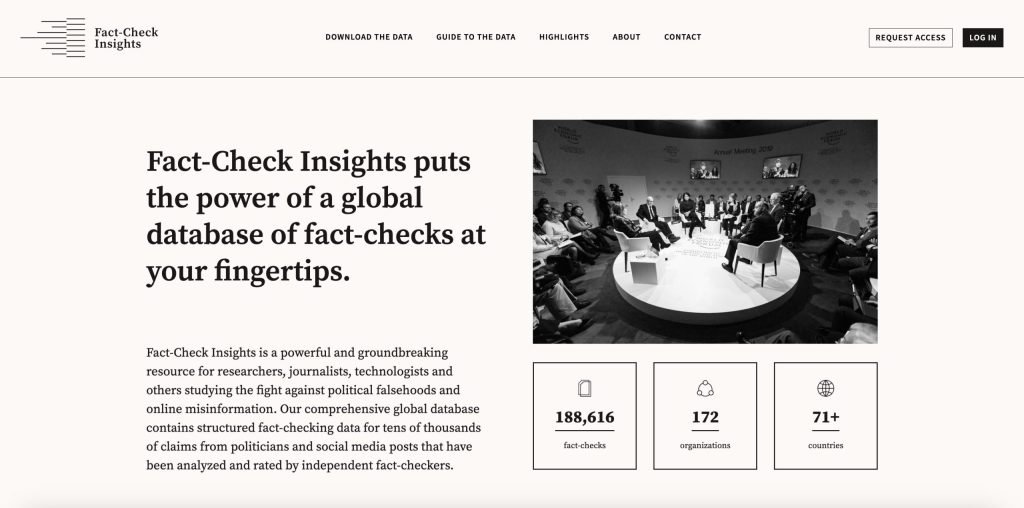

Researchers around the world are digging into the trove of data available from our Fact-Check Insights project, with plans to use it for everything from benchmarking the performance of large language models to studying the moderation of humor online.

Since launching in December, the Fact-Check Insights dataset has been downloaded more than 300 times. The dataset is updated daily and made available at no cost to researchers by the Duke Reporters’ Lab, with support from the Google News Initiative.

Fact-Check Insights contains structured data from more than 240,000 claims made by political figures and social media accounts that have been analyzed and rated by independent fact-checkers. The dataset is powered by ClaimReview and MediaReview, twin tagging systems that allow fact-checkers to enter standardized data about their fact-checks, such as the statement being checked, the speaker, the date, and the rating.

Users have found great value in the data.

Marcin Sawiński, a researcher in the Department of Information Systems at the Poznań University of Economics and Business in Poland, is part of a team using ClaimReview data for a multiyear project aimed at developing a tool to assess the credibility of online sources and detect false information using AI.

“With nearly a quarter of a million items reviewed by hundreds of fact-checking organizations worldwide, we gain instant access to a vast portion of the fact-checking output from the past several years,” Sawiński writes. “Manually tracking such a large number of fact-checking websites and performing web data extraction would be prohibitively labor-intensive. The ready-made dataset enables us to conduct comprehensive cross-lingual and cross-regional analyses of fake-news narratives with much less effort.”

The OpenFact project, which is financed by the National Center for Research and Development in Poland, uses natural language processing and machine learning techniques to focus on specific topics.

“Shifting our efforts from direct web data extraction to the cleanup, disambiguation, and harmonization of ClaimReview data has significantly reduced our workload and increased our reach,” Sawiński writes.

Other researchers who have downloaded the dataset plan to use it for benchmarking the performance of large language models for fact-checking uses. Others are investigating the response to false information by social media platforms.

Ariadna Matamoros-Fernández, a senior lecturer in digital media in the School of Communication at Queensland University of Technology in Australia, plans to use the Fact-Check Insights dataset as part of her research into identifying and moderating humor on digital platforms.

“I am using the dataset to find concrete examples of humorous posts that have been fact-checked to discuss these examples in interviews with factcheckers,” Matamoros-Fernández writes. “I am also using the dataset to use examples of posts that have been flagged as being satire, memes, humour, parody etc to test whether different foundation models (GPT4/Gemini) are good at assessing these posts.”

The goals of her research include trying to “better understand the dynamics of harmful humour online” and creating best practices to tackle them. She has received a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award from the Australian Research Council to support her work.

Rafael Aparecido Martins Frade, a doctoral student working with the Spanish fact-checking organization Newtral, plans to utilize the data in his research on using AI to tackle disinformation.

“I am currently researching automated fact-checking, namely multi-modal claim matching,” he writes of his work. “The objective is to develop models and mechanisms to help fight the spread of fake news. Some of the applications we’re planning to work on are euroscepticism, climate emergency and health.”

Researchers who have downloaded the Fact-Check Insights dataset have also provided the Reporters’ Lab with feedback on making the data more usable.

Enrico Zuccolotto, a master’s degree student in artificial intelligence at the Polytechnic University of Milan, performed a thorough review of the dataset, offering suggestions aimed at reducing duplication and filling in missing data.

While the data available from Fact-Check Insights is primarily presented in the original form submitted by fact-checking organizations, the Reporters’ Lab has made small attempts to enhance the data’s clarity, and we will continue to make such adjustments where feasible.

Researchers who have questions about the dataset can refer to the “Guide to the Data” page, which includes a table outlining the fields included, along with examples (see the “What you can expect when you download the data” section). The Fact-Check Insights dataset is available for download in JSON and CSV formats.

Access is free for researchers, journalists, technologists and others in the field, but registration is required.

Related: What exactly is the Fact-Check Insights dataset?

What exactly is the Fact-Check Insights dataset?

Get details about data that can aid your misinformation research

By Erica Ryan - June 20, 2024

Since its launch in December, the Fact-Check Insights dataset has been downloaded hundreds of times by researchers who are studying misinformation and developing technologies to boost fact-checking.

But what should you expect if you want to use the dataset for your work?

First, you will need to register. The Duke Reporters’ Lab, which maintains the dataset with support from the Google News Initiative, generally approves applications within a week. The dataset is intended for academics, researchers, journalists and/or fact-checkers.

Once you are approved, you will be able to download the dataset in either CSV or JSON format.

Those files include the metadata for more than 200,000 fact-checks that have been tagged with ClaimReview and/or MediaReview markup.

The two tagging systems — ClaimReview for text-based claims, MediaReview for images and videos — are used by fact-checking organizations across the globe. ClaimReview summarizes a fact-check, noting the person and claim being checked and a conclusion about its accuracy. MediaReview allows fact-checkers to share their assessment of whether a given image, video, meme or other piece of media has been manipulated.

The Reporters’ Lab collects ClaimReview and MediaReview data when it is submitted by fact-checkers. We filter the data to include only reputable fact-checking organizations that have qualified to be listed in our database, which we have been publishing and updating for a decade. We also work to reduce duplicate entries, and standardize the names of fact-checking organizations. However, for the most part, the data is presented in its original form as submitted by fact-checking organizations.

Here are the fields that you can expect to be included in the dataset, along with examples:

ClaimReview

| CSV Key | Description | Example Value |

|---|---|---|

| id | Unique ID for each ClaimReview entry | 6c4f3a30-2ec1-4e2e-9b57-41ad876223e5 |

| @context | Link to schema.org, the home of ClaimReview | https://schema.org |

| @type | Type of schema being used | ClaimReview |

| claimReviewed | The claim/statement that was assessed by the fact-checker | Marsha Blackburn “voted against the Reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, which attempts to protect women from domestic violence, stalking, and date rape.” |

| datePublished | The date the fact-check article was published | 10/9/18 |

| url | The URL of the fact-check article | https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2018/oct/09/taylor-swift/taylor-swift-marsha-blackburn-voted-against-reauth/ |

| author.@type | Type of author | Organization |

| author.name | The name of the fact-checking organization that submitted the fact-check | PolitiFact |

| author.url | The main URL of the fact-checking organization | http://www.politifact.com |

| itemReviewed.@type | Type of item reviewed | Claim |

| itemReviewed.author.name | The person or group that made the claim that was assessed by the fact-checker | Taylor Swift |

| itemReviewed.author.@type | Type of speaker | Person |

| itemReviewed.author.sameAs | URLs that help establish the identity of the person or group that made the claim, such as a Wikipedia page (rarely used) | https://www.taylorswift.com/ |

| reviewRating.@type | Type of review | Rating |

| reviewRating.ratingValue | An optional numerical value assigned to a fact-checker’s rating. Not standardized. (Note: 1.) The ClaimReview schema specifies the use of an integer for the ratingValue, worstRating and bestRating fields. 2.) For organziations that use ratings scales (such as PolitiFact), if the rating chosen falls on the scale, the numerical rating will appear in the ratingValue field. 3.) If the rating isn’t on the scale (ratings that use custom text, or special categories like Flip Flops), the ratingValue field will be empty, but worstRating and bestRating will still appear. 4.) For organizations that don’t use ratings that fall on a numerical scale, all three fields will be blank.) |

8 |

| reviewRating.alternateName | The fact-checker’s conclusion about the accuracy of the claim in text form — either a rating, like “Half True,” or a short summary, like “No evidence” | Mostly True |

| author.image | The logo of the fact-checking organization | https://d10r9aj6omusou.cloudfront.net/factstream-logo-image-61554e34-b525-4723-b7ae-d1860eaa2296.png |

| itemReviewed.name | The location where the claim was made | in an Instagram post |

| itemReviewed.datePublished | The date the claim was made | 10/7/18 |

| itemReviewed.firstAppearance.url | The URL of the first known appearance of the claim | https://www.instagram.com/p/BopoXpYnCes/?hl=en |

| itemReviewed.firstAppearance.type | Type of content being referenced | Creative Work |

| itemReviewed.author.image | An image of the person or group that made the claim | https://static.politifact.com/CACHE/images/politifact/mugs/taylor_swift_mug/03dfe1b483ec8a57b6fe18297ce7f9fd.jpg |

| reviewRating.ratingExplanation | One to two short sentences providing context and information that led to the fact-checker’s conclusion | Blackburn voted in favor of a Republican alternative that lacked discrimination protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity. But Blackburn did vote no on the final version that became law. |

| itemReviewed.author.jobTitle | A title or description of the person or group that made the claim | Mega pop star |

| reviewRating.bestRating | An optional numerical value representing what rating a fact-checker would assign to the most accurate content it assesses. See note on “reviewRating.ratingValue” field above. | 10 |

| reviewRating.worstRating | An optional numerical value representing what rating a fact-checker would assign to the least accurate content it assesses. See note on “reviewRating.ratingValue” field above. | 0 |

| reviewRating.image | An image representing the fact-checker’s rating, such as the Truth-O-Meter | https://static.politifact.com/politifact/rulings/meter-mostly-true.jpg |

| itemReviewed.appearance.1.url to itemReviewed.appearance.15.url | A URL where the claim appeared. This field has been limited to the first 15 URLs submitted for the stability of the CSV. See the JSON download for complete “appearance” data. | https://www.instagram.com/p/BopoXpYnCes/?hl=en |

| itemReviewed.appearance.1.@type to itemReviewed.appearance.15.@type | Type of content being referenced | CreativeWork |

MediaReview

| CSV Key | Description | Example Value |

|---|---|---|

| id | Unique ID for each MediaReview entry | 2bfe531d-ff53-40f5-8114-a819db22ca8b |

| @context | Link to schema.org, the home of MediaReview | https://schema.org |

| @type | Type of schema being used | MediaReview |

| datePublished | The date the fact-check article was published | 2020-07-02 |

| mediaAuthenticityCategory | The fact-checker’s conclusion about whether the media was manipulated, ranging from “Original” to “Transformed” (More detail) | Transformed |

| originalMediaContextDescription | A short sentence explaining the original context if media is used out of context | In this case, there was no original context. But this is a text field. |

| originalMediaLink | Link to the original, non-manipulated version of the media (if available) | https://example.com/ |

| url | The URL of the fact-check article that assesses a piece of media | https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2020/jul/02/facebook-posts/no-taylor-swift-didnt-say-we-should-remove-statue-/ |

| author.@type | Type of author | Organization |

| author.name | The name of the fact-checking organization | PolitiFact |

| author.url | The URL of the fact-checking organization | http://www.politifact.com |

| itemReviewed.contentUrl | The URL of the post containing the media that was fact-checked | https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10223714143346243&set=a.3020234149519&type=3&theater |

| itemReviewed.startTime | Timestamp of video edit (in HH:MM:SS format) | 0:01:00 |

| itemReviewed.endTime | Ending timestamp of video edit, if applicable (in HH:MM:SS format) | 0:02:00 |

| itemReviewed.@type | Type of media being reviewed | ImageObject / VideoObject / AudioObject |

Please note that not every fact-check will contain data for every field.

For the JSON version of the table above, please see the “What you can expect when you download the data” section of the Guide on the Fact-Check Insights website. The Guide page also contains tips for working with the ClaimReview and MediaReview data.

If you continue to have questions about the Fact-Check Insights dataset, please reach out to hello@factcheckinsights.org.

Related: Researchers mine Fact-Check Insights data to explore many facets of misinfo

With half the planet going to the polls in 2024, fact-checking sputters

Referees are hard to come by in a globe-spanning election year that desperately needs more fact-checking

By Mark Stencel, Erica Ryan and Joel Luther - May 30, 2024

This year’s elections are a global convergence of ballots, checkboxes and thumb prints, with voters in more than 64 countries and all of the European Union heading to the polls. Based on a Time magazine estimate, this democratic spectacle could potentially involve the equivalent of 49% of the planet’s population.

Just one problem: There aren’t enough referees.

For most of the past decade and a half, the global fact-checking community served that role, and experienced years of rapid growth. But based on the most recent counts from the Duke Reporters’ Lab, the number of reporting and research teams that routinely intercept political lies and disinformation is plateauing — exactly at the time when the world needs fact-checkers most.

Our latest count showed as many as 457 fact-checking projects in 111 countries were active over the past two years.

But so far in 2024, that number has shrunk to 439.

The runup to June’s sprawling E.U. vote and this fall’s U.S. election campaign may nudge the numbers upward slightly. But a slight upswing is nothing like fact-checking’s rocket-like ascent over the past 15 years.

When PolitiFact won a Pulitzer Prize for its U.S. fact-checking in 2009, the award signaled the potential of this important new form of journalism. At that time, we counted 17 sites that consistently did similar work.

By 2016, the year of the U.K’s final Brexit referendum and Donald J. Trump’s White House win, the count was 190 — an 11-fold increase.

Four years later, during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and Trump’s failed reelection campaign, the revised tally for 2020 more than doubled to 421.

An abrupt shift

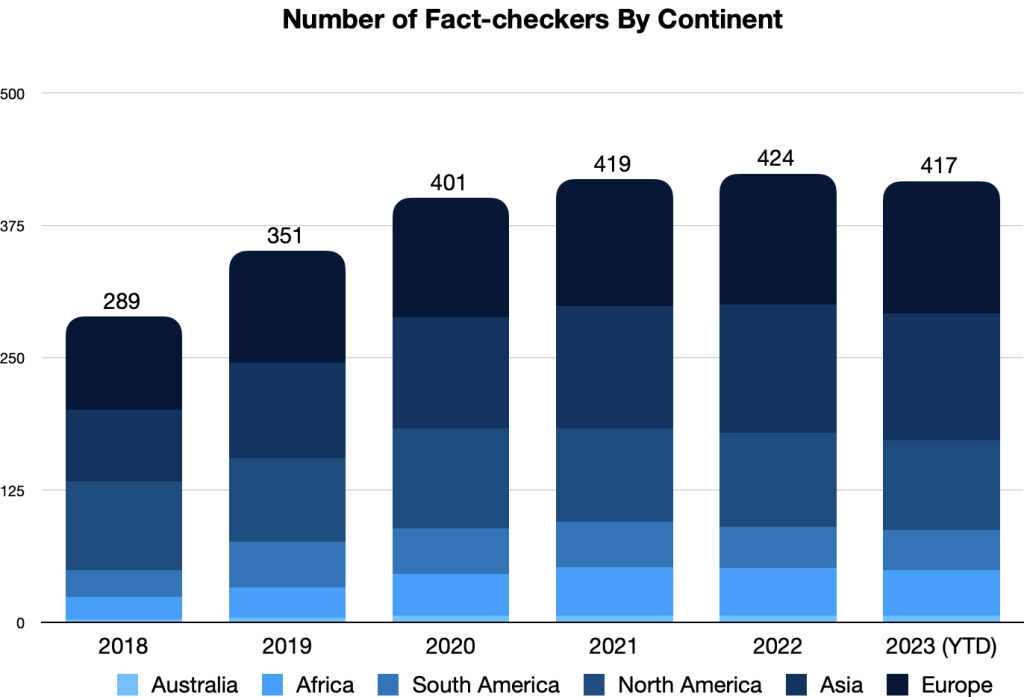

In the years since our Lab began producing this annual census in 2014, fact-checking has become an international enterprise — quickly growing the community on six of the seven continents. Until it didn’t.

In Asia, for instance, the numbers of fact-checking operations and bureaus jumped from 94 in 2019 to 124 in 2021 — a 32% increase. And much the same happened in Africa, where 32 fact-checkers in 2019 became 54 in 2021 — up 69%.

But the pace dramatically leveled off over the following years. From 2021 to 2023, the range in Asia’s fact-checking count was between 124 and 130. In Africa, the number hovered around 55.

The leveling off started earlier in other parts of the world. From 2020 to 2023, the range in Europe was between 120 and 135.

The number in the Americas decreased. From 2020 to 2023, South America went from 44 to 39 while North America went from 94 to 90.

The flatter Earth

Our conversations with fact-checkers indicate a few factors contributed to the flattening.

Like every industry and institution, fact-checkers had to manage their teams through the pandemic. And in the early days of COVID-19, they also had to rejigger their organizations to cover the slow-motion disaster. That meant adding health reporting to beats that more typically focused on a mix of politics, hoaxes and digital scams.

Fact-checkers, like other journalists, also have struggled to raise money to pay their operating costs.

Atop those challenges, a certain amount of turnover was common in the fact-checking business. Teams in one place would decide to close up shop, often for financial reasons. At the same time, new fact-checkers would start their own ventures.

For most of the past decade, the number of new fact-checking operations far outnumbered the ones that had shut down — often by wide margins. In one year, 2017, the ratio was 11-to-1, with 55 new fact-checkers and five that closed down.

Then there was last year: 2023 was the first time there were more departing fact-checking teams than new ones — 18 closures to 10 starts.

Roughing the refs

Perhaps the biggest challenge some fact-checking projects face has less to do with the fundamentals of running a newsroom or a research team. It’s about the vitriol that fact-checkers encounter from hostile governments and politicians, as well as their supporters

From Bangladesh to Brazil, scurrilous attempts to undermine fact-checking are familiar tactics, especially for the reporters and researchers who work in countries where press freedom hardly exists.

Based on data from Reporters Without Borders’ recently released World Press Freedom Index, 69 fact-checking organizations in the Reporters’ Lab list are based in about 20 countries with situations that are rated “very serious.” Starting from the most serious places, those fact-checkers operate in Syria (1), Afghanistan (2), Iran (1), China (5), Myanmar (2), Egypt (4), Iraq (2), Cuba (1), Belarus (1), Saudi Arabia (1), Bangladesh (5), Azerbaijan (1), India (26), Turkey (3), Venezuela (3), Yemen (2), Pakistan (2), Cambodia (1), Sri Lanka (5) and Sudan (1). The list from Reporters Without Borders also counts Palestine, where there are at least three fact-checking teams. Palestine is between Turkey and Venezuela in the Index.

Even in less dangerous places, politicians have enlisted companies and institutions to use economic pressure against fact-checkers.

The fact-checking community saw multiple examples in 2023. In South Korea, conservative politicians pressured the country’s leading search engine, Naver, to cancel its financial support for SNU FactCheck — a project of the Seoul National University Institute of Communications Research. Since 2017, SNU FactCheck’s director, EunRyung Chong, worked with her country’s leading media organizations to showcase fact-checking reports using a shared system for rating questionable claims — especially the claims of politicians. Naver not only dropped its financial support, but it also took away SNU FactCheck’s access to the search company’s audience. Ultimately, the European Climate Foundation, a nonpartisan organization based in the Netherlands, stepped in to provide support that allowed SNU FactCheck and its media partners to continue their work — including coverage of last month’s National Assembly election.

In Australia, conservative politicians were more successful in derailing a years-long partnership between the country’s ABC News network and RMIT University. Egged on by the conservative outlets of News Corp Australia, lawmakers attacked the reporting of RMIT ABC Fact Check based on claims of bias and misuse of public funds. ABC has since announced its plans to sever the collaboration with the university and launch a new program aimed at misinformation.

Agence France-Presse is one of the largest fact-checking organizations, with teams posted in dozens of bureaus around the world. The French news agency lists most of the participating journalists — but not all. “While we endeavour to be as transparent as possible about our staff, some countries and environments are more hostile than others when it comes to journalism,” the list notes. “For that reason, some of the journalists on our… team will not be named below to protect their safety. ”

[June 6, 2024: This article was updated to better characterize the reasons that led to the end of the RMIT ABC Fact Check partnership after seven years.]About the Reporters’ Lab and its Census

The Duke Reporters’ Lab began tracking the international fact-checking community in 2014, when director Bill Adair organized a group of about 50 people who gathered in London for what became the first Global Fact meeting. Subsequent Global Facts led to the creation of the International Fact-Checking Network and its Code of Principles.

The Reporters’ Lab and the IFCN use similar criteria to keep track of fact-checkers, but use somewhat different methods and metrics. Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database and census reports. If you have questions, updates or additions, please contact Mark Stencel, Erica Ryan or Joel Luther.

Previous Fact-checking Census Reports

Note: The Reporters’ Lab regularly updates our counts as we identify and add new sites to our fact-checking database. As a result, numbers from earlier census reports differ from year to year.

- April 2014

- January 2015

- February 2016

- February 2017

- February 2018

- June 2019

- June 2020

- June 2021

- June 2022

- June 2023

Duke lab gives fact-checkers, researchers new tools to thwart misinformation

Powerful global databases offer new insights into political claims and hoaxes, and help debunk manipulated images and video

By Duke Reporters' Lab - December 15, 2023

Researchers and journalists covering the battle against misinformation have a powerful new tool in their arsenal — a groundbreaking collection of fact-checking data that covers tens of thousands of harmful political claims and online hoaxes.

Fact-Check Insights, a comprehensive global database from the Duke Reporters’ Lab that launches this week, contains structured data from more than 180,000 claims from political figures and social media accounts that have been analyzed and rated by independent fact-checkers. The project was created with support from the Google News Initiative.

The Fact-Check Insights database is powered by ClaimReview — which has been called the world’s most successful structured journalism project — and its sibling MediaReview. The twin tagging systems allow fact-checkers to enter standardized data about their fact-checks, such as the statement being fact-checked, the speaker, the date, and the rating.

“ClaimReview and MediaReview are the secret sauce of fact-checking,” said Bill Adair, director of the Reporters’ Lab and the Knight professor of journalism and public policy at Duke. “This data will give researchers a much easier way to study how politicians lie, where false information spreads, and other vital topics so we can better combat misinformation.”

This rich, important dataset is updated daily, summarizing articles from dozens of fact-checkers around the world, including well-known organizations such as FactCheck.org, PesaCheck, Factly, Full Fact, Chequeado and Pagella Politica. It is ready-made for download in JSON and CSV formats. Access is free for researchers, journalists, technologists and others in the field, but registration is required.

Archiving tool for fact-checkers

Along with Fact-Check Insights, the Reporters’ Lab is launching MediaVault, a unique and unprecedented tool for fact-checkers who are working to debunk manipulated images and videos shared around the world.

MediaVault is a cutting-edge system that collects and stores images and videos that have been analyzed by reputable fact-checking organizations. The MediaVault archive allows fact-checkers to maintain a vital portion of their work, which would otherwise disappear when posts are removed from social media platforms. It also enables quicker research and identification of previously published images and videos in misleading social media posts.

“MediaVault is the first archival system that is specifically tailored to the needs of fact-checkers,” Adair said. “Our team developed this system after seeing too many posts go missing after being fact-checked. We realized fact-checkers needed a custom-made solution.”

MediaVault is free for use by fact-checkers, journalists and others working to debunk misinformation shared online, but registration is required. This project also received support from the Google News Initiative.

The Reporters’ Lab team behind the Fact-Check Insights and MediaVault projects includes lead technologist Christopher Guess, project manager Erica Ryan, ClaimReview/MediaReview manager Joel Luther, and Lab co-director Mark Stencel. The team was assisted by Duke University researcher Asa Royal, along with developer Justin Reese and designer Joanna Fonte of Bad Idea Factory.

Misinformation spreads, but fact-checking has leveled off

10th annual fact-checking census from the Reporters' Lab tracks an ongoing slowdown

By Mark Stencel, Erica Ryan and Joel Luther - June 21, 2023

While much of the world’s news media has struggled to find solid footing in the digital age, the number of fact-checking outlets reliably rocketed upward for years — from a mere 11 sites in 2008 to 424 in 2022.

But the long strides of the past decade and a half have slowed to a more trudging pace, despite increasing concerns around the world about the impact of manipulated media, political lies and other forms of dangerous hoaxes and rumors.

In our 10th annual fact-checking census, the Duke Reporters’ Lab counts 417 fact-checkers that are active so far in 2023, verifying and debunking misinformation in more than 100 countries and 69 languages.

While the count of fact-checkers routinely fluctuates, the current number is roughly the same as it was in 2022 and 2021.

In more blunt terms: Fact-checking’s growth seems to have leveled off.

Since 2018, the number of fact-checking sites has grown by 47%. While that’s an increase of 135, it is far slower than the preceding five years, when the numbers grew more than two and a half times, or the six-fold increase over the five years before that.

There also are important regional patterns. With lingering public health issues, climate disasters, and Russia’s ongoing war with Ukraine, factual information is still hard to come by in important corners of the world.

Before 2020, there was a significant growth spurt among fact-checking projects in Africa, Asia, Europe and South America. At the same time, North American fact-checking began to slow. Since then, growth in the fact-checking movement has plateaued in most of the world.

The Long Haul

One good sign for fact-checking is the sustainability and longevity of many key players in the field. Almost half of the fact-checking organizations in the Reporters’ Lab count have been active for five years or more. And roughly 50 of them have been active for 10 years or more.

The average lifespan of an active fact-checking site is less than six years. The average lifespan of the 139 fact-checkers that are now inactive was not quite three years.

But the baby boom has ended. Since 2019, when a bumper crop of 83 fact-checkers went online, the number of new sites each year has steadily declined. The Reporters’ Lab count for 2022 is at 20, plus three additions in 2023 as of this June. That reduced the rate of growth from three years earlier by 72%.

The number of fact-checkers that closed down in that same period also declined, but not as dramatically. That means the net count of new and departing sites has gone from 66 in 2019 to 11 in 2022, plus one addition so far in 2023.

The Downshift

The Downshift

As was the case for much of the world, the pandemic period certainly contributed to the slower growth. But another reason is the widespread adoption of fact-checking by journalists and other researchers from nonpartisan think tanks and good-government groups in recent years. That has broadened the number of people doing fact-checking but created less need for news organizations dedicated to the unique form of journalism.

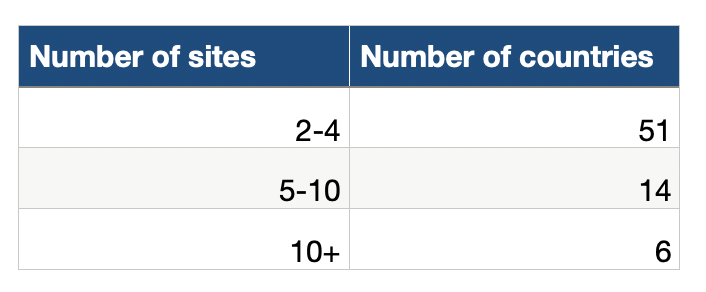

With teams working in 108 countries, just over half of the nations represented in the United Nations have at least one organization that already produces fact-checks for digital media, newspapers, TV reports or radio. So in some countries, the audience for fact-checks might be a bit saturated. As of June, there are 71 countries that have more than one fact-checker.

Another reason for the slower pace is that launching new fact-checking projects is challenging — especially in countries with repressive governments, limited press freedom and safety concerns for journalists …. In other words, places where fact-checking is most needed.

The 2023 World Press Freedom Index rates press conditions as “very serious” in 31 countries. And almost half of those countries (15 of 31) do not have any fact-checking sites. They are Bahrain, Djibouti, Eritrea, Honduras, Kuwait, Laos, Nicaragua, North Korea, Oman, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam and Yemen. The Index also includes Palestine, the status of which is contested.

Remarkably, there are 62 fact-checking services in the 16 other countries on the “very serious” list. And in eight of those countries, there is more than one site. India, which ranks 161 out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index, is home to half of those 62 sites. The other countries with more than one fact-checking organization are Bangladesh, China, Venezuela, Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt and Myanmar.

In some cases, fact-checkers from those countries must do their work from other parts of the world or hide their identities to protect themselves or their families. That typically means those journalists and researchers must work anonymously or report on a country as expats from somewhere else. Sometimes both.

At least three fact-checking teams from the Middle East take those precautions: Fact-Nameh (“The Book of Facts”), which reports on Iran from Canada; Tech 4 Peace, an Iraq-focused site that also has members who work in Canada; and Syria’s Verify-Sy, whose staff includes people who operate from Turkey and Europe.

Two other examples are elTOQUE DeFacto, a project of a Cuban news website that is legally registered in Poland; and the fact-checkers at the Belarusian Investigative Center, which is based in the Czech Republic.

In other cases, existing fact-checking organizations have also established separate operations in difficult places. The Indian sites BOOM and Fact Crescendo have set-up fact-checking services in Bangladesh, while the French news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP) has fact-checkers that report on misinformation from Hong Kong, India and Myanmar, among others.

There still are places where fact-checking is growing, and much of that has to do with organizations that have multiple outlets and bureaus — such as AFP, as noted above. The French international news service has about 50 active sites aimed at audiences in various countries and various languages.

India-based Fact Crescendo launched two new channels in 2022 — one for Thailand and another focused broadly on climate issues. Along with two other outlets the previous year, Fact Crescendo now has a total of eight sites.

The 2022 midterm elections in the United States added six new local fact-checking outlets to our global tally, all at the state level. Three of the new fact-checkers were the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, The Nevada Independent and Wisconsin Watch, all of whom used a platform called Gigafact that helped generate quick-hit “Fact Briefs” for their audiences. But the Arizona Center is no longer participating. (For more about the 2022 U.S. elections see “From Fact Deserts to Fact Streams” — a March 2023 report from the Reporters’ Lab.)

About the Reporters’ Lab and Its Census

The Duke Reporters’ Lab began tracking the international fact-checking community in 2014, when director Bill Adair organized a group of about 50 people who gathered in London for what became the first Global Fact meeting. Subsequent Global Facts led to the creation of the International Fact-Checking Network and its Code of Principles.

The Reporters’ Lab and the IFCN use similar criteria to keep track of fact-checkers, but use somewhat different methods and metrics. Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database and census reports. If you have questions, updates or additions, please contact Mark Stencel, Erica Ryan or Joel Luther.

* * *

Related links: Previous fact-checking census reports

April 2014: https://reporterslab.org/duke-study-finds-fact-checking-growing-around-the-world/

January 2015: https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking-census-finds-growth-around-world/

February 2016: https://reporterslab.org/global-fact-checking-up-50-percent/

February 2017: https://reporterslab.org/international-fact-checking-gains-ground/

February 2018: https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking-triples-over-four-years/

June 2019: https://reporterslab.org/number-of-fact-checking-outlets-surges-to-188-in-more-than-60-countries/

June 2020: https://reporterslab.org/annual-census-finds-nearly-300-fact-checking-projects-around-the-world/

June 2021: https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking-census-shows-slower-growth/

Vast gaps in fact-checking across the U.S. allow politicians to elude scrutiny

A Reporters' Lab review of local fact-checking finds only a small percentage of politicians and other public officials are held accountable for the accuracy of the claims they make.

By Mark Stencel, Erica Ryan, Sofia Bliss-Carrascosa, Belen Bricchi and Joel Luther - March 29, 2023

The candidates running last year for an open seat in Ohio’s 13th Congressional District exchanged a relentless barrage of scathing claims, counterclaims and counter-counterclaims.

Emilia Sykes was a former Democratic leader in the state legislature who came from a prominent political family. Her opponent called Sykes a lying, liberal career politician who raised her own pay, increased taxes on gas and retirement accounts, and took money from Medicare funds to “pay for free healthcare for illegals.” Other attack ads warned voters that the Democrat backed legislation that would release dangerous criminals from jail.1

Sykes’ opponent, Republican Madison Gesiotto Gilbert, was an attorney, a former Miss Ohio, and a prominent supporter of former President Donald Trump. Sykes’ and her backers called Gilbert a liar who would “push for tax cuts for millionaires” and slash Social Security and Medicare. Gilbert backed a total abortion ban with no exceptions, they warned (“not even if the rape victim is a 10 year old girl”) and she had the support of political groups that aim to “outlaw birth control.”2

Voters in one of the country’s most contested U.S. House races heard those allegations over and over — in TV ads, social media posts and from the candidates themselves.

But were any of those statements and allegations true? Who knows?

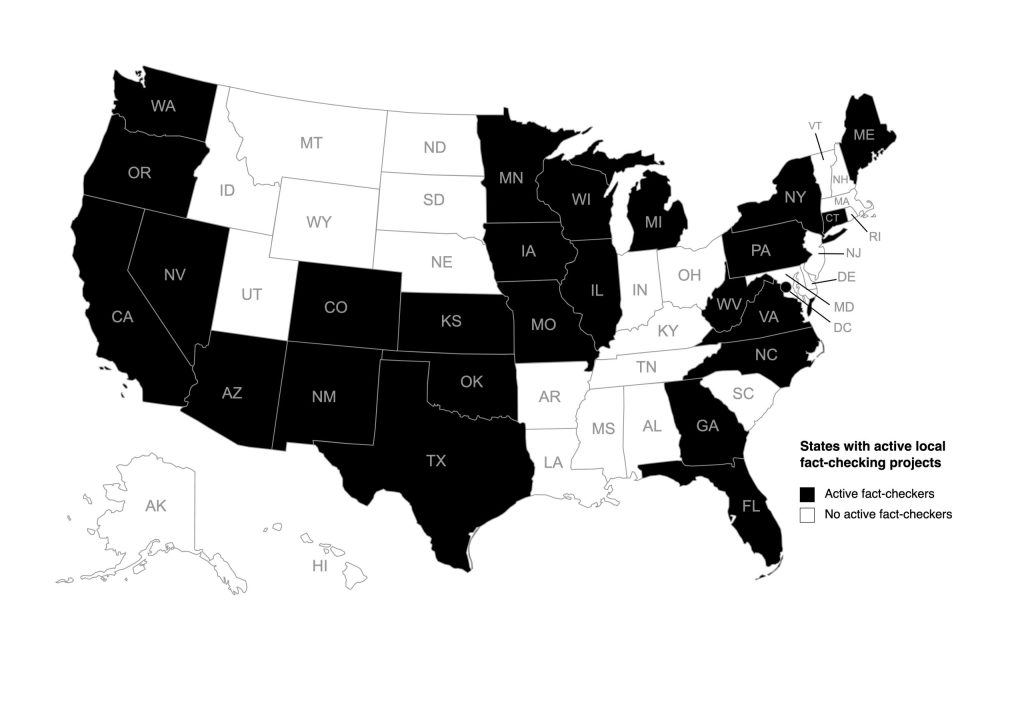

Ohio was one of 25 states where no statewide or local media outlet consistently fact-checked political statements. So voters in the 13th District were on their own to sort out the truth and the lies.

But their experience was not unique. Throughout the country, few politicians had to worry about being held accountable for exaggerations or lies in ads or other claims during the campaign.

An extensive review by the Duke Reporters’ Lab of candidates and races that were fact-checked found only a small percentage of politicians and public officials were held accountable for the accuracy of what they said.

The results were striking.

Governors were the most likely elected officials to face review by fact-checkers at the state and local level. But still fewer than half of the governors had even a single statement checked (19 out of 50).

For those serving in Congress, the chances of being checked were even lower. Only 33 of 435 U.S. representatives (8%) were checked. In the U.S. Senate, a mere 16 of 100 lawmakers were checked by their home state news media.

The smaller the office, the smaller the chance of being checked. Out of 7,386 state legislative seats, just 47 of those lawmakers were checked (0.6%). And among the more than 1,400 U.S. mayors of cities of 30,000 people or more, just seven were checked (0.5%).

These results build on an earlier Reporters’ Lab report3 immediately after the election, which showed vast geographical gaps in fact-checking at the state and local level. Voters in these “fact deserts” have few, if any, ways to keep up with misleading political claims on TV and social media. Nor can they easily hold public officials and institutions accountable for any inaccuracies and disinformation they spread.

Longstanding national fact-checking projects fill in some of the gaps. FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, The Washington Post, and the Associated Press sometimes focus on high-profile races at the state and local level. They and other national media outlets also monitor the statements of prominent state-level politicians who have their eyes fixed on higher offices — such as the White House.

But our review of the 2022 election finds that the legacy fact-checking groups have not scaled to the vast size and scope of the American political system. Voters need more fact-checks, on more politicians, more quickly. And fact-checkers need to develop more robust and creative ways to distribute and showcase those findings.

We found big gaps in coverage, but also opportunities for some relatively easy collaborations. Politicians and campaigns repeatedly use the same lines and talking points. Fact-checkers sometimes cite each other’s work when the same claims pop up in other places and other mouths. But there’s relatively little organized collaboration among fact-checkers to quickly respond to recycled claims. Collaborative projects in the international fact-checking community offer potential templates. Technology investments would help, too.

Who’s Getting Fact-Checked?

To examine the state of regional fact-checking, the Duke Reporters’ Lab identified 50 active and locally focused fact-checking projects from 25 states and the District of Columbia.4 That count was little changed from the national election years since 2016, when an average of 46 fact-checking projects were active at the state and local level.

The fact-checking came from a mix of TV news stations, newspaper companies, digital media sites and services, and two public radio stations. PolitiFact’s state news affiliates also include two university partnerships, including a student newspaper. (See the full report for a complete list and descriptions.)

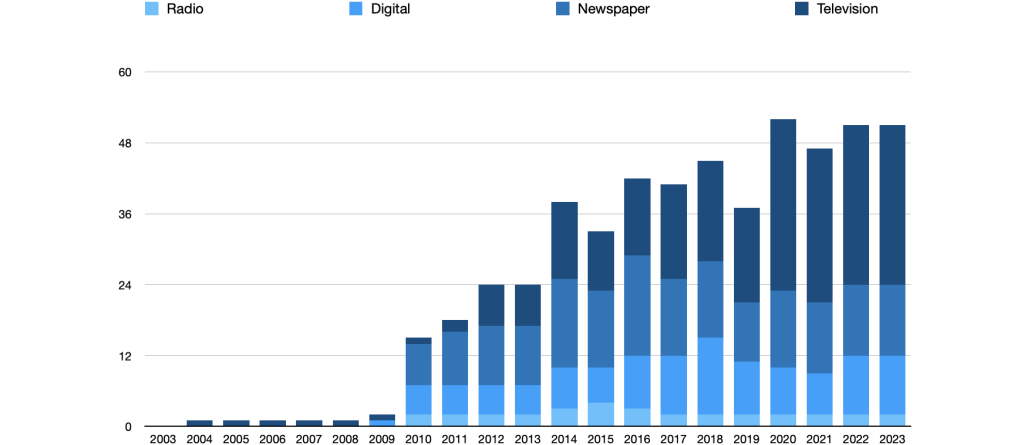

Active Local Fact-Checking Outlets by Year

Journalists from those news organizations cranked out 976 fact-checks, verifying the accuracy of more than 1,300 claims from Jan. 1, 2022, to Election Day.

But thousands more claims went unchecked. That became clear when we began to determine who was getting fact-checked.

As part of our research, we reviewed the fact-checkers’ output in text, video and audio format. We identified a “claim” as a statement or image that served as the basis of a news report that analyzed its accuracy based on reliable evidence. That included a mix of political statements as well as other kinds of fact-checks — such as local issues, social trends and health concerns.

We excluded explanatory stories that did not analyze a specific claim or reach a conclusion. Of the more than 970 fact-checks we reviewed, about 13% examined multiple claims.

The Reporters’ Lab found that a vast majority of politicians at the state and local level elude the fact-checking process, from city council to statewide office. But elected officials and candidates in some places got more scrutiny than others.

Some interesting findings:

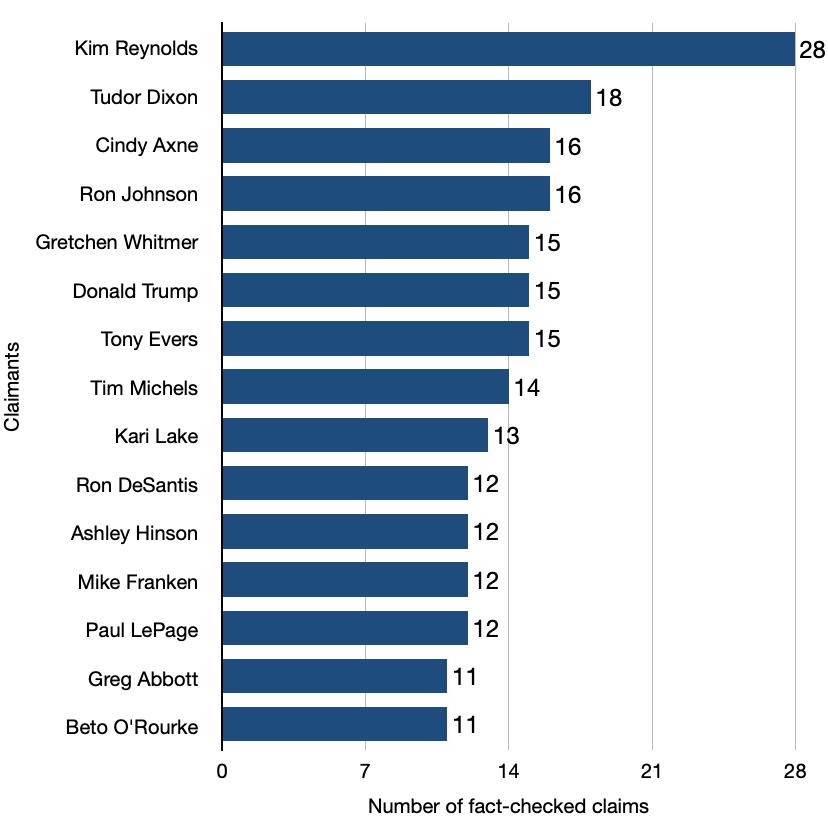

The most-checked politician was Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds, a Republican. Reynolds topped the list with 28 claims checked, largely because of two in-depth articles from the Gazette Fact Checker in Cedar Rapids, which covered 10 claims from her Condition of the State address in January 2022, and another 10 from her delivery of the Republican response to President Joe Biden’s State of the Union in March.

Other more frequently checked politicians included Michigan gubernatorial challenger Tudor Dixon, a Republican (18); Cindy Axne, a Democrat who lost her bid for reelection to a U.S. House seat in Iowa (16); and incumbent U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, a Republican (16).

Also near the top of the list were former President Trump, a Republican (15), who was sometimes checked on claims during local appearances; Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat (15); Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat (15); Evers’ Republican challenger Tim Michels (14); Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake, a Republican (13); and Florida’s Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis (12).

Most-Checked Politicians

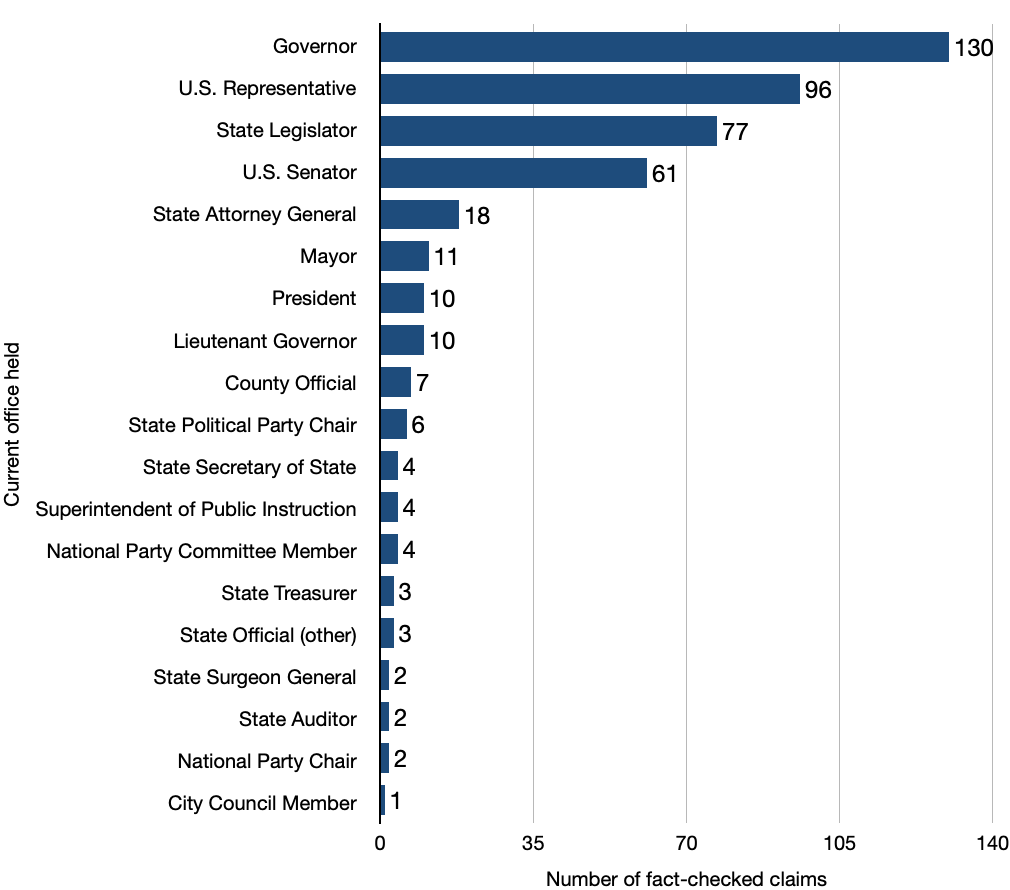

Overall, individual claims by sitting governors were checked 130 times (10% of claims); by U.S. representatives 96 times (7%); by state legislators 77 times (6%); by U.S. senators 61 times (5%); and by mayors 11 times (1%).

Most-Checked Politicians By Office Held

For comparison, President Joe Biden’s claims were checked more than 100 times by national fact-checkers from PolitiFact, The Washington Post and others.

While these numbers focus on direct checking of the politicians themselves, fact-checkers also analyzed claims by other partisan sources, including deep-pocket political organizations running attack ads in many races.

There was more checking of Republicans/conservative politicians and political groups (553 claims, or 42%) than Democratic/progressive groups (382 claims, or 29%). If we look strictly at the 942 claims from claimants we identified as political, 59% were Republican/conservative and 41% were Democratic/progressive.

Read the full report here.

Read the full report here.

Our Recommendations

Fact-checking is a challenging type of journalism. It requires speed, meticulous research and a thick skin. It also requires a willingness to call things as they are, instead of hiding behind the misleading niceties of both-siderism. And yet, over the past decade, dozens of state and local news organizations have adopted this new type of journalism.

The 50 fact-checking programs we examined during last year’s midterm election invested time, energy and money to combat political falsehoods and push back against other types of misinformation. Even at a time of upheaval in the local news business, we have seen TV news stations, newspaper companies, and nonprofit newsrooms embrace this mission.

But all this work is not enough.

Misinformation and disinformation spread far, fast and at a scale that is almost impossible for news media fact-checkers to keep pace. If journalists aim to reestablish a common set of facts, we need to do more fact-checking.

Our recommendations for dramatically increasing local media’s capacity for fact-checking include:

Invest in more fact-checking

The challenge: Despite the diligent work of local fact-checking outlets in 25 states and the District of Columbia, only a relative handful of politicians and public officials were ever fact-checked. And in half the country, there was no active fact-checking at all.

The recommendation: It is clear that an investment in this vital journalism is sorely needed. Voters in “fact desert” states like Ohio and New Hampshire will be key to the 2024 elections. And those voters should be able to trust in local journalism to provide a check on the lies that politicians are sure to peddle in political ads, debates and other campaign events.

Even in states where local fact-checking efforts exist, they are severely outmatched by a tsunami of claims, as political organizations pump billions of dollars into campaign ads, and social media messages accelerate the spread of misinformation far and wide. The low numbers of claims checked locally in the 2022 Senate races in Arizona, Georgia, Nevada and Pennsylvania demonstrate that additional help is needed in manpower and financial resources for the journalists trying to keep up with the campaign cycle.

One way to increase the volume of local fact-checking would be to incentivize projects like Gigafact and PolitiFact. These existing models can be replicated by other organizations and added in additional states. The Gigafact partners in Arizona, Nevada and Wisconsin produced dozens of 140-word “fact briefs” in the run-up to the 2022 election. These structured fact-checks, which answer yes/no questions, have proved popular with audiences. Dee J. Hall, managing editor at Wisconsin Watch, which participated in the Gigafact pilot in 2022, reported that eight of the organization’s ten most popular stories in November were fact briefs.

The journalism education community can also help. During the 2022 election, PolitiFact worked with the journalism department at West Virginia University and the student newspaper at the University of Iowa to produce fact-checks for voters in their states. Expanding that model, potentially in collaboration with other national fact-checkers, could transform most of the barren “fact deserts” we’ve described in time for the 2024 general election campaign.

Elevate fact-checking

The challenge: Fact-checking is still a niche form of reporting. It shares DNA with explanatory and investigative journalism. But it is rarely discussed at major news media conferences. There are few forums for fact-checkers at the state and local level to compare their efforts, learn from one another and focus on their distinctive reporting problems.

The recommendation: As we continue increasing the volume of local fact-checking, audiences and potential funders need to view fact-checking with the same importance as investigative work. Investigative reporting has been a cornerstone of local news outlets’ identity and public service mission for decades. Fact-checking should be equally revered. Both are vital forms of journalism that are closely related to each other.

Some local news outlets already take this approach, with their investigative teams also producing fact-checking of claims. For example, 4 Investigates Fact Check at KOB-TV in New Mexico is an offshoot of its 4 Investigates team, and FactFinder 12 Fact Check at KWCH-TV in Kansas uses a similar model.

Fact-checkers also can elevate their work by explaining it more forcefully — on-air, online and even in person. This is an essential way to promote trust in their work. We found that 17 state and local fact-checking efforts do not provide any explanation of their process or methodology to their audiences. Offering this kind of basic guidance does not require creating and maintaining separate dedicated “about” or methodology pages. Instead, some fact-checkers, such as ConnectiFact and the Gazette Fact Checker in Iowa, embed explanations directly within their fact-checks. In this mobile era, that in-line approach might well be more important. Likewise, as TV continues to play an increasing role in fact-checking, broadcasters also need to help their viewers understand what they’re seeing.

Embrace technology and collaborate

The challenge: Several national fact-checkers in the United States work closely together with the Reporters’ Lab, as well as other academic researchers and independent developers, to test new approaches to their work. We’ve seen that same spirit of community in the International Fact-Checking Network at the Poynter Institute, which has fostered cross-border collaborations and technology initiatives. In contrast, few state and local press in the United States have the capacity or technological know-how to experiment on their own. Fact-checking also has a low-profile in journalism’s investigative and tech circles.

The recommendation: There is a critical need for more investment in technology to assist fact-checkers at the state and local level. As bad actors push misinformation on social media and politicians take advantage of new technologies to mislead voters, an equal effort must be made to boost the truth.

AI can be leveraged to better track the spread of misinformation, such as catching repetitions of false talking points that catch on and circulate all around the country. A talking point tracker could help fact-checkers prioritize and respond to false claims that have already been fact-checked.

AI can also be leveraged to help with the debunking of false claims. Once a repeated talking point has been identified, a system using AI could then create the building blocks of a fact-check that a journalist could review and publish.

But none of these ideas will get very far unless journalists are willing to collaborate. Collaboration can cut down on duplication and allow more effort to be spent on fact-checking new claims. The use of technology would also have a greater impact if more organizations are willing to swap data and make use of each others’ research.

Make fact-checking easier to find

The challenge: Fact-checking in the United States has grown significantly since 2017. But fact-checks are still easy to miss on cluttered digital news feeds. Existing technology can help fact-checkers raise their profiles. But some state and local fact-checks don’t even have basic features that call attention to their reporting.

The recommendation: Nearly 180 fact-checking projects across the United States and around the world have embraced open-source systems designed to provide data that elevate their work in search results and on large social media and messaging services. State and local fact-checkers should adopt this system as well.

The Reporters’ Lab joined with Google and Schema.org to develop a tagging system called ClaimReview. ClaimReview provides data that major digital platforms can use to recognize and suppress misinformation on their feeds. A second, related schema called MediaReview is generating similar data for visual misinformation.

ClaimReview has helped feed a prominent collection of recent fact-checks on the front of the Google News page in half a dozen countries, including the U.S. But so far, most state and local fact-checking projects are not using ClaimReview.

Meanwhile, the regional fact-checkers have even more foundational work to do. That more than a quarter of the active fact-checkers (13 of 50) have no dedicated page or tag for the public to find these stories is disappointing. Overcoming the limitations of inflexible publishing systems often make simple things hard. But all fact-checkers need to do more to showcase their work. Fact-checks have a long shelf life and enormous value to their audiences.

This project was a team effort. The report was written and led by Mark Stencel, co-director of the Duke Reporters’ Lab, and project manager Erica Ryan. Student researchers Sofia Bliss-Carrascosa and Belén Bricchi were significant contributors, as was Joel Luther, research and outreach coordinator for ClaimReview and MediaReview at the Reporters’ Lab.

Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database. The Lab continually collects new information about the fact-checkers it identifies, such as when they launched and how long they last. If you know of a fact-checking project that has been missed, please contact Mark Stencel and Erica Ryan at the Reporters’ Lab.

Our thanks to Knight Foundation’s journalism program for supporting this research.

Disclosure: Stencel is an unpaid contributing editor to PolitiFact North Carolina.

1 https://nrcc.org/2022/08/31/fact-check-sykes-lies-to-oh-voters-in-first-tv-ad/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCQz6FCMMzo

https://congressionalleadershipfund.org/sykes-sided-with-criminals-over-public-safety/

2 https://host2.adimpact.com/admo/viewer/a9400662-bc20-4e34-9a44-42d478efa451/

https://dccc.org/dccc-releases-new-tv-ad-in-oh-13-wrong/

3 https://reporterslab.org/fact-deserts-leave-states-vulnerable-to-election-lies/

4 After an earlier report in November 2022, our Lab identified a few more election-year fact-checking efforts. That meant our total count for the year increased from 46 to 50. And the number of states that had fact-checking efforts in that period increased from 21 to 25.

Fact deserts leave states vulnerable to election lies

Politicians in 29 states get little scrutiny for what they say, while local fact-checkers in other places struggle to keep pace with campaign misinformation.

By Mark Stencel, Erica Ryan and Belen Bricchi - November 16, 2022

Amid the political lies and misinformation that spread across the country throughout the 2022 midterm elections, statements by candidates in 29 states rarely faced the scrutiny of independent fact-checkers.

Why? Because there weren’t any local fact-checkers.

Even in the places where diligent local media outlets regularly made active efforts to verify the accuracy of political claims, the volume of questionable statements in debates, speeches, campaign ads and social posts far outpaced the fact-checkers’ ability to set the record straight.

An initial survey by Reporters’ Lab at Duke University identified 46 locally focused fact-checking projects during this year’s campaign in 21 states and the District of Columbia. That count is little changed in the national election years since 2016, when an average of 47 fact-checking projects were active at the state and local level.

Active State/Local Fact-Checkers in the U.S., 2003-22

There’s also been lots of turnover among local fact-checking projects over time. At least 40 projects have come and gone since 2010. And fact-checking is not always front and center, even among the news outlets that devote considerable effort and time to this reporting.

While some fact-checkers consistently produce reports from election to election, many others are campaign-season one-offs. And the overwhelming emphasis on campaign claims can produce a fact-vacuum after the votes are counted — when elected officials, party operatives and others in the political process continue to make erroneous and misleading statements.

Fact-checks also can be hard for readers and viewers to find — sometimes appearing only in a broader scroll of state political news, with little effort to make this vital reporting stand out or to showcase it on a separate page.

The Duke Reporters’ Lab conducted this initial survey to assess the state of local fact-checking during the 2022 midterm elections. The Lab first began tracking fact-checking projects across the United States and around the world in 2014 and maintains a global database and map of fact-checking projects.

While 29 states currently appear to have no fact-checking projects that regularly report on claims from politicians or social media at the local level, residents may encounter occasional one-off fact-checks from their state’s media outlets.

Among the states lacking dedicated fact-checking projects are four that had hotly contested Senate or governor races this fall — New Hampshire, Kansas, Ohio and Oregon.

The states with the most robust fact-checking in terms of projects based there include Texas with five outlets; Iowa and North Carolina with four; and Florida, Michigan and Wisconsin with three each.

Competition seems to generate additional fact-checking. States with active fact-checking projects tend to have at least two (14 states of the 21), while seven states and D.C. have a single locally focused project.

Local television stations are the most active fact-check producers. Of the outlets that generated fact-checks at the state and local level this year, more than half are local television stations. That’s a change over the past two decades, when newspapers and their websites were the primary outlets for local fact-checks.

Who Produces Local Fact-Checks?

Almost all local fact-checking projects are run by media outlets, while several are based at universities or nonprofit organizations. The university-related fact-checkers are Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication; The Daily Iowan, the University of Iowa’s independent student newspaper; and West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media. All three are state affiliates of PolitiFact, the prolific national fact-checking organization based at the nonprofit Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Florida.

National news partnerships and media owners drive a significant amount of local fact-checking. Of the 46 projects, almost a quarter are affiliated with PolitiFact, while another half-dozen are among the most active local stations participating in the Verify fact-checking project by TV company Tegna. In addition, five Graham Media Group television stations use a unified Trust Index brand at the local level.

One of the newest efforts to encourage local fact-checking is Repustar’s Gigafact, a non-profit project that partnered with three newsrooms to counter misinformation during the midterms. The Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, The Nevada Independent and Wisconsin Watch produced “fact briefs,” which are short, timely reports that answer yes or no questions, such as “Is Nevada’s violent crime rate higher than the national average?”

Nearly 40 percent of the fact-checkers in the Lab’s count got their start since 2020, including 11 projects in that year alone. In contrast, the oldest fact-checker, WISC-TV in Madison, Wisconsin, began producing its Reality Check segments almost two decades ago, in 2004. It’s among 12 fact-checkers that have been active for 10 years or more.

Another new initiative launched in April to increase Spanish language fact-checking at the local level in the U.S. — but with the help of two prominent international fact-checking organizations.

Factchequeado, a partnership between Maldita.es of Spain and Chequeado in Argentina, has built a network of 27 allies, including 19 local news outlets in the U.S. through which they share fact-checks and media literacy content. Currently, the majority of Factchequeado fact-checks are produced at the national level by its own staff. Through its U.S. partnerships, Factchequeado aims to train Hispanic journalists to produce original fact-checks in Spanish at the local level.

The Reporters’ Lab conducted this survey with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, which also has helped fund the Lab’s work on automated fact-checking. The Lab intends to follow up its initial assessment of the local fact-checking landscape with a post-election report that will dive into some of the challenges facing journalists trying to do this vital work. Our follow-up report will explore the content of local fact-checkers’ work in 2022, including data on whom they fact-checked and their approaches to rating claims. We will interview local reporters, producers and editors about public and political feedback and their editorial processes and methodologies. We also intend to examine why some local fact-checking initiatives are short-lived election-year efforts while others have carried on consistently for many years.

Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database. The Lab continually collects new information about the fact-checkers it identifies, such as when they launched and how long they last. If you know of a fact-checking project that has been missed, please contact Mark Stencel and Erica Ryan at the Reporters’ Lab.

Joel Luther of the Reporters’ Lab contributed to this report.

Appendix: Local Fact-Checking Projects

Arizona

Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting (Gigafact) | Phoenix

Fact-checking for Repustar’s Gigafact Project by an independent, nonprofit newsroom in Phoenix funded by individual donors, foundations, fee-for-service revenue and other sources. Repustar is a privately-funded benefit corporation based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

PolitiFact Arizona | Phoenix

The Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University is PolitiFact’s local affiliate in Arizona. PolitiFact previously worked in Arizona with KNXV-TV (ABC15), ABC’s local affiliate in Phoenix, as part of partnership with the station’s owner, Scripps TV Station Group. (KNXV-TV had previously produced its own “Truth Test” segments.) PolitiFact’s national staff maintained the site starting with the 2018 midterm election cycle until the fact-checking organization partnered with ASU in 2022.

California

PolitiFact California | Sacramento

Affiliate of PolitiFact, staffed by reporters at Capital Public Radio.

Sacramento Bee Fact Check | Sacramento

Fact-checks by Sacramento Bee reporters appear in its Capitol Alert section, especially in election years. Began as an “Ad Watch” feature focused on political advertising.

Colorado

9News Truth Test | Denver

NBC’s local TV affiliate in Denver has long done political fact-checking, particularly during elections. In addition, the Tegna-owned station also actively contributes to the Verify initiative — a companywide fact-checking and explanatory journalism project that involves a mix of local stories and national reporting shared across more than 60 stations (https://www.9news.com/verify). 9News relies on funding from advertising and local carriage fees from cable, satellite and digital TV service providers.

CBS4 Reality Check | Denver

Election-year fact-checks from Denver’s local, CBS-owned commercial TV affiliate.

District of Columbia

WUSA9 Verify | Washington

WUSA9 is among the most active contributors in Tegna’s Verify initiative — a companywide fact-checking and explanatory journalism project that involves a mix of local stories and national reporting shared across more than 60 stations. The Washington-area’s CBS affiliate relies on funding from advertising and local carriage fees from cable, satellite and digital TV service providers.

Florida

News4Jax Trust Index | Jacksonville

Fact-checking by the news team at WJXT-TV (News4Jax), an independent commercial TV station in Jacksonville, Florida. News4Jax is owned by the Graham Media Group, a commercial media company whose stations launched their “Trust Index” reporting during the 2020 U.S. elections with help and training from Fathm, a media lab and international consulting group.

News 6 Trust Index | Orlando

Fact-checking by the news team at WKMG-TV (News 6), the CBS affiliate in Orlando, Florida. News 6 is owned by the Graham Media Group, a commercial media company whose regional TV stations launched their “Trust Index” reporting during the 2020 U.S. elections with help and training from Fathm, a media lab and international consulting group.

PolitiFact Florida | St. Petersburg

PolitiFact’s reporting on the state is produced in affiliation with the Tampa Bay Times. The newspaper’s bureau in Washington, D.C., was the fact-checking service’s original home before it was folded into the Poynter Institute — a non-profit media training center in St. Petersburg, Florida, that also owns the Times and its commercial publishing company. From 2010 to 2017, the Miami Herald was also a PolitiFact Florida reporting and distribution partner.

Georgia

11 Alive Verify | Atlanta

WXIA is among the most active contributors in Tegna’s Verify initiative — a companywide fact-checking and explanatory journalism project that involves a mix of local stories and national reporting shared across more than 60 stations. The Atlanta-area’s NBC affiliate relies on funding from advertising and local carriage fees from cable, satellite and digital TV service providers.

Illinois

PolitiFact Illinois | Chicago

Affiliate of PolitiFact, staffed by reporters and researchers from the Better Government Association, a nonprofit watchdog organization founded in 1923 that focuses on investigative journalism. PolitiFact’s previous news partner in the state was Reboot Illinois, a for-profit digital news service.

Iowa

Gazette Fact Checker | Cedar Rapids

Fact-checks by reporters at The Cedar Rapids Gazette. The newspaper previously worked on its fact-checks in collaboration with KCRG-TV, a local TV station the Gazette owned until 2015.

KCCI’s Get the Facts | Des Moines

Fact-checks of campaign ads during election cycles by reporters at the Des Moines, Iowa, CBS affiliate, a commercial station owned by Hearst Television.

KCRG-TV’s “I9 Fact Checker” | Cedar Rapids

Occasional fact-checks presented by commercial station KCRG-TV’s “I9 Investigation” team. The local ABC affiliate in Cedar Rapids was previously owned by the area’s local newspaper, The Cedar Rapids Gazette. The two news organizations worked together on fact-checks from 2014 to 2018.

PolitiFact Iowa | Iowa City

Affiliate of PolitiFact, staffed by reporters at The Daily Iowan, the independent student newspaper at the University of Iowa. PolitiFact’s previous state partner in Iowa was the Des Moines Register.

Maine

Bangor Daily News Ad Watch | Bangor

Fact-checks of campaign ads during election season by staffers at the Bangor daily newspaper.

Portland Press Herald | Portland

Fact-checks of campaign ads during election cycles by staffers at the daily newspaper in Portland, Maine.

Michigan

Bridge Michigan | Detroit

An ongoing reporting project published mainly in election years by Bridge Magazine, an online journal published by the non-profit Center for Michigan. Originally called The Truth Squad, the project began as a standalone site before it merged with the center and its magazine in 2012. The Bridge’s fact-checkers also have collaborated with public media’s Michigan Radio.

Local 4 Trust Index | Detroit

Fact-checking by the news team at WDIV-TV (Local 4), the NBC affiliate for Detroit, Michigan. Local 4 is owned by the Graham Media Group, a commercial media company whose regional TV stations launched their “Trust Index” reporting during the 2020 U.S. elections with help and training from Fathm, a media lab and international consulting group.

PolitiFact Michigan | Detroit

Affiliate of PolitiFact, staffed by reporters from the Detroit Free Press. The newspaper previously did fact-checking on its own during the 2014 midterm elections.

Minnesota

5 Eyewitness News Truth Test | St. Paul

Election season fact-checking by the local ABC affiliate’s political reporter.

CBS Minnesota Reality Check | Minneapolis

Fact-checking by the news staff at the local CBS affiliate in Minneapolis.

Missouri

KY3 Fact Finders | Springfield

Fact-checks by an anchor/reporter for the NBC affiliate in Springfield, Missouri. Focuses on rumors and questions from viewers.

News 4 Fact Check | St. Louis

Election season fact-checks by reporters at CBS’s local affiliate in St. Louis.

Nevada