Fact-checkers are now found in at least 102 countries – more than half the nations in the world.

The latest census by the Duke Reporters’ Lab identified 341 active fact-checking projects, up 51 from last June’s report.

But after years of steady and sometimes rapid growth, there are signs that trend is slowing, even though misleading content and political lies have played a growing role in contentious elections and the global response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Our tally revealed a slowdown in the number of new fact-checkers, especially when we looked at the upward trajectory of projects since the Lab began its yearly survey and global fact-checking map seven years ago.

The number of fact-checking projects that launched since the most recent Reporters’ Lab census was more than three times fewer than the number that started in the 12 months before that, based on our adjusted tally.

From July 2019 to June 2020, there were 61 new fact-checkers. In the year since then, there were 19.

Meanwhile, 21 fact-checkers shut down in that same two-year period beginning in June 2019. And 54 additions to the Duke database in that same period were fact-checkers that were already up and running prior to the 2019 census.

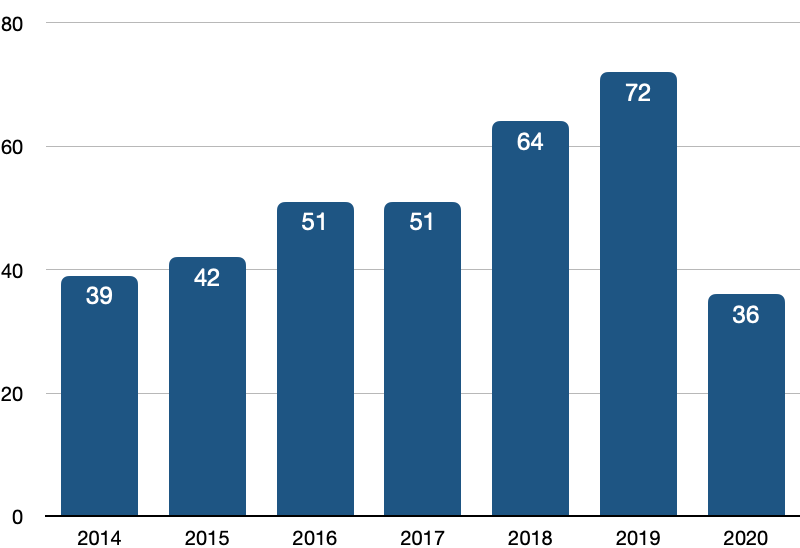

Looking at the count by calendar year also underscored the slowdown in the time of COVID.

The Reporters’ Lab counted 36 fact-checking projects that launched in 2020. That was below the annual average of 53 for the preceding six calendar years – and less than half the number of startups that began fact-checking in 2019. The 2020 launches were also the lowest number of new fact-checkers we’ve counted since 2014.

New Fact Checkers by Year

(Note: The adjusted number of 2020 launches may increase slightly over time as the Reporters’ Lab identifies other fact-checkers we have not yet discovered.)

The slowdown comes after a period of rapid expansion that began in 2016. That was the year when the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the presidential race in the United States raised public alarm about the impact of misinformation.

In response, major tech companies such as Facebook and Google elevated fact-checks on their platforms and provided grants, direct funding and other incentives for new and existing fact-checking organizations. (Disclosure: Google and Facebook fund some of the Duke lab’s research on technologies for fact-checkers. )

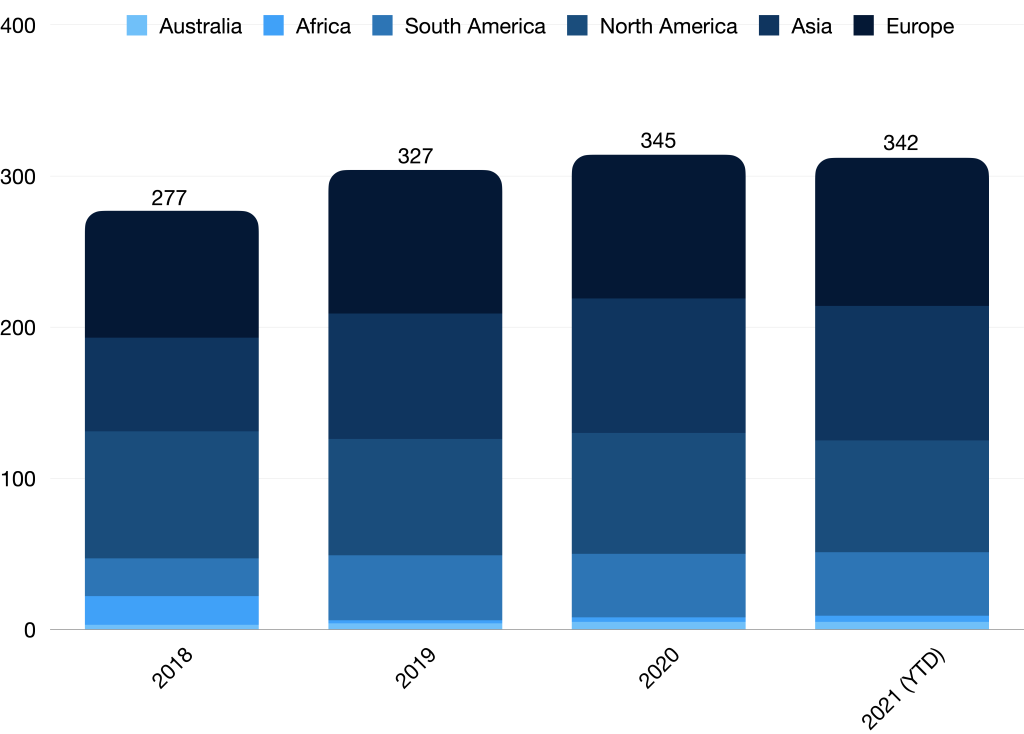

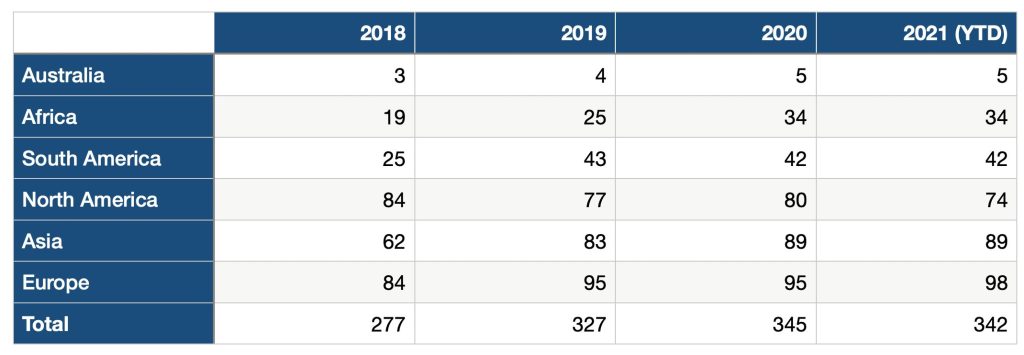

The 2018-2020 numbers presented below are adjusted from earlier census reports to include fact-checkers that were subsequently added to our database.

Active Fact-Checkers by Year

Note: 2021 YTD includes one fact-checker that closed in 2021.

Growth has been steady on almost every continent except in North America. In the United States, where fact-checking first took off in the early 2010s, there are 61 active fact-checkers now. That’s down slightly from the 2020 election year, when there were 66. But the U.S. is still home to more fact-checking projects than any other country. Of the current U.S. fact-checkers, more than half (35 of 61) focus on state and local politics.

Fact-Checkers by Continent

Among other details we found in this year’s census:

- More countries, more staying power: Based on our adjusted count, fact-checkers were active in at least 47 countries in 2014. That more than doubled to 102 now. And most of the fact-checkers that started in 2014 or earlier (71 out of 122) are still active today.

- Fact-checking is more multilingual: The active fact-checkers produce reports in nearly 70 languages, from Albanian to Urdu. English is the most common, used on 146 different sites, followed by Spanish (53), French (33), Arabic (14), Portuguese (12), Korean (11) and German (10). Fact-checkers in multilingual countries often present their work in more than one language – either in translation on the same site, or on different sites tailored for specific language communities, including original reporting for those audiences.

- More than media: Half of the current fact-checkers (195 of 341) are affiliated with media organizations, including national news publishers and broadcasters, local news sources and digital-only outlets. But there are other models, too. At least 37 are affiliated with non-profit groups, think tanks and nongovernmental organizations and 26 are affiliated academic institutions. Some of the fact-checkers involve cross-organization partnerships and have multiple affiliations. But to be listed in our database, the fact-checking must be organized and produced in a journalistic fashion.

- Turnover: In addition to the 341 current fact-checkers, the Reporters’ Lab database and map also include 112 inactive projects. From 2014 to 2020, an average of 15 fact-checking projects a year close down. Limited funding and expiring grants are among the most common reasons fact-checkers shuttered their sites. But there also are short-run, election year projects and partnerships that intentionally close down once the voting is over. Of all the inactive projects, 38 produced fact-checks for a year or less. The average lifespan of an inactive fact-checker is two years and three months. The active fact-checkers have been in business twice as long – an average of more than four and a half years.

The Reporters’ Lab process for selecting fact-checkers for its database is similar to the standards used by the International Fact Checking Network – a project based at the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Florida. IFCN currently involves 109 organizations that each agree to a code of principles. The Lab’s database includes all the IFCN signatories, but it also counts any related outlets – such as the state-level news partners of PolitiFact in the United States, the wide network of multilingual fact-checking sites that France’s AFP has built across its global bureau system, and the fact-checking teams Africa Check and PesaCheck have mobilized in countries across Africa.

Reporters’ Lab project manager Erica Ryan and student researchers Amelia Goldstein and Leah Boyd contributed to this year’s report.

About the census: Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database. The Lab continually collects new information about the fact-checkers it identifies, such as when they launched and how long they last. That’s why the updated numbers for earlier years in this report are higher than the counts the Lab included in earlier reports. If you have questions, updates or additions, please contact Mark Stencel or Joel Luther.

Related Links: Previous fact-checking census reports

Comments closed

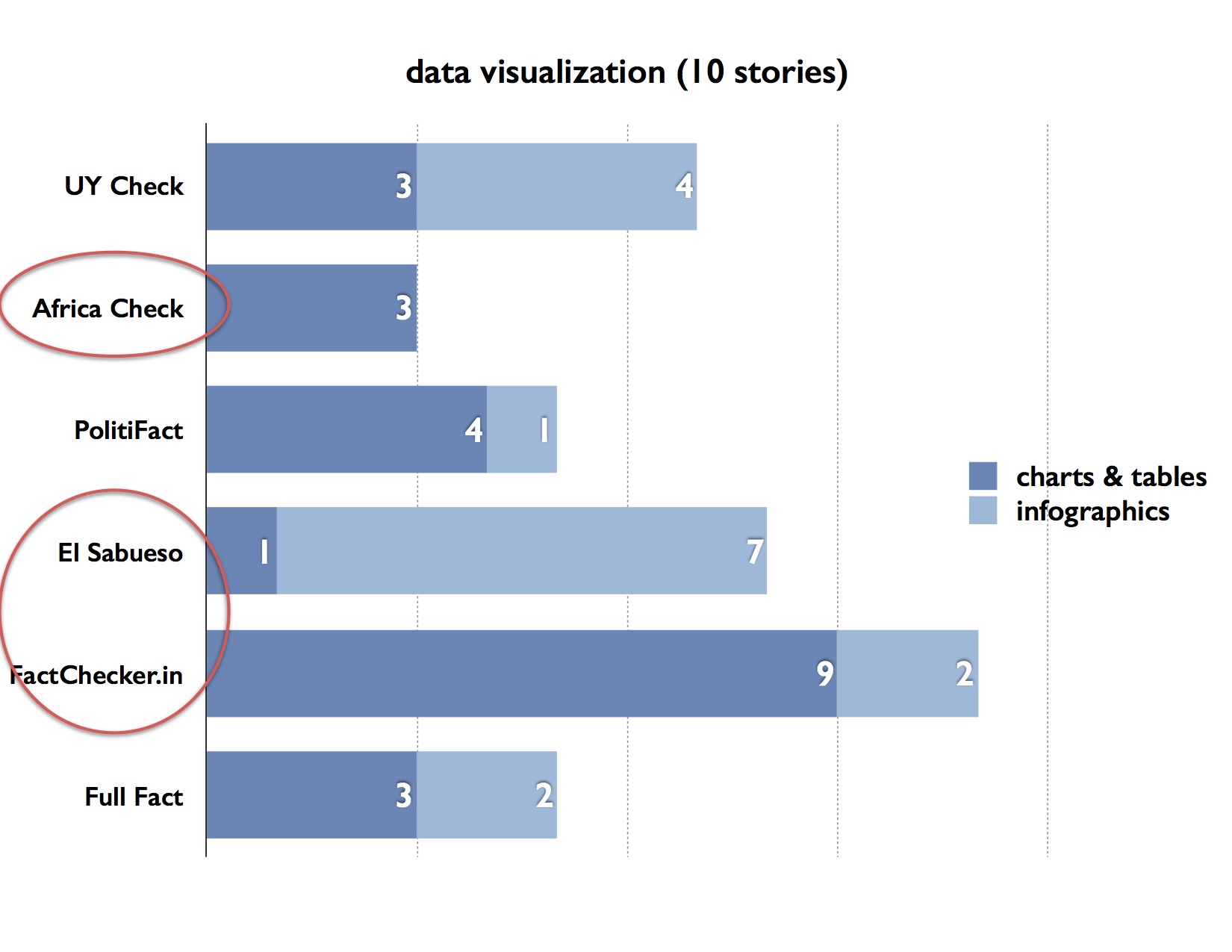

Graves and his researchers found a surprising range in the length of the fact-checking articles. UYCheck from Uruguay had the longest articles, with an average word count of 1,148, followed by Africa Check at 1,009 and PolitiFact at 983.

Graves and his researchers found a surprising range in the length of the fact-checking articles. UYCheck from Uruguay had the longest articles, with an average word count of 1,148, followed by Africa Check at 1,009 and PolitiFact at 983.