The 200-person attendee list for next week’s Global Fact 4 summit in Madrid is up 80 from last year’s meeting in Buenos Aires, and more than twice what it was in London two years ago. And with good reason: The number of fact-checkers has been growing too, driven by concerns about a global epidemic of misinformation, viral hoaxes and official lying.

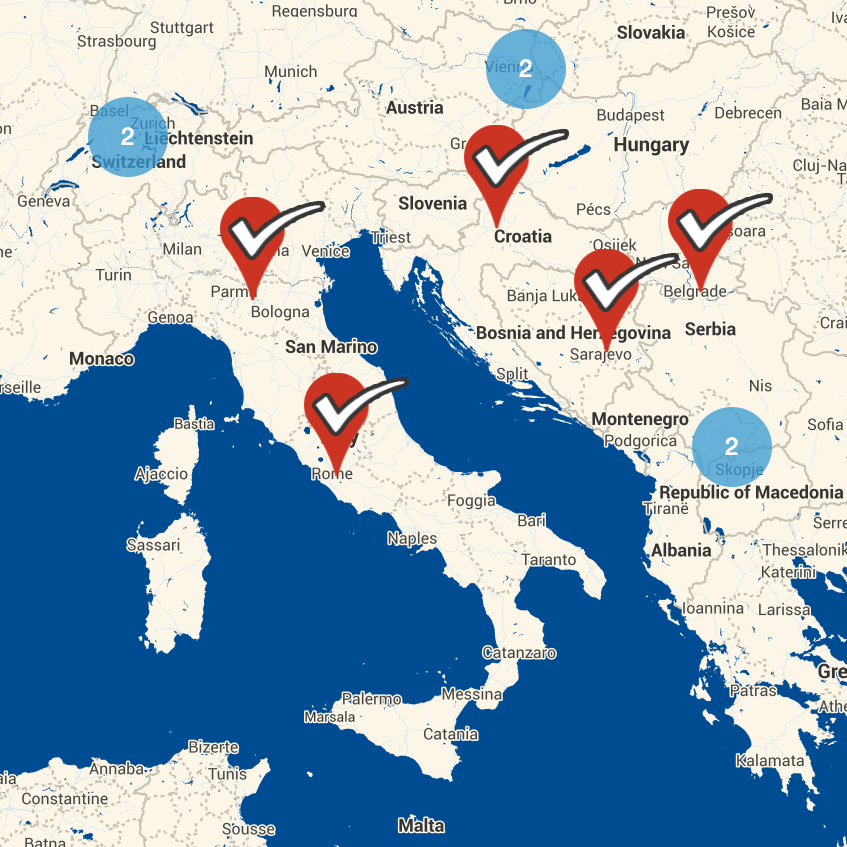

The Duke Reporters’ Lab database of international fact-checking initiatives now counts 126 active projects in 49 countries. That’s up 20 percent from the 105 projects we tallied a year ago. And that year-over-year increase continues the growth we found in for our most recent annual fact-checking census in February.

Active Fact-Checkers by Continent

Africa: 4

Asia: 14

Australia: 2

Europe: 46

North America: 47

South America: 13

NOTE: All the numbers presented throughout this article are as of June 30, 2017. An updated map, global tally and country-by-country lists are available on the Reporters’ Lab fact-checking page.

It’s great to see so many new sites: 17 of the 126 fact-checkers opened for business in the past 12 months. One of the newest, the Ferret Fact Service in Edinburgh, launched just nine weeks ago. And there was the welcome return of Australia’s ABC. Government funding cuts ended that project last year, but it returned from an 11-month hiatus on June 5 as a jointly branded partnership of the public broadcasting company and RMIT University in Melbourne. And the same Toronto-based team of technology activists that built a site four years ago to track Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s campaign promises launched a new fact-checking service in April: Fact-Nameh (“The Book of Facts”), the PolitiFact of Iran.

Of the fact-checkers that launched in the past year, seven were in Europe, four were in North America, three were in Asia and three were in South America. And all appeared in countries with roiling political situations plagued by false claims and misinformation that made global headlines — from presidential impeachments (Brazil and South Korea) to an attempted coup (Turkey) to intense immigration fights (everywhere!) to nationwide campaigns and voting (South Korea and Turkey again, plus Austria, Iran, Italy, Kosovo, the U.K and, um, the U.S. — with Germany’s turn coming in September).

If ever there was a time for fact-checking, this was it.

The United States is home to a third (42) of the fact-checkers we track. We also found that 16 other countries have at least two fact-checking projects, and seven of those have three or more, including Brazil (8), the United Kingdom (6), France (5), South Korea (5), Ukraine (4) and Canada (3).

We saw an encouraging sign about quality: One-fifth of the fact-checkers in the database (25 of the 126) are already verified signatories of International Fact-Checking Network’s newly established Code of Principles. And that number will grow because independent evaluators are reviewing additional applications. The code was written by an IFCN committee last summer to encourage best practices such as fairness, a commitment to correcting errors, and transparency on sources, methodology and funding. Facebook is using IFCN’s Code to identify trustworthy non-partisan fact-checking partners to help flag fake news and other misinformation.

Most of the sites, about six out of 10, are affiliated with established news media organizations. The rest are a mix of independent journalism and research projects, many of which are affiliated with universities, think tanks and non-governmental groups instead of existing media companies.

The ties to media companies are especially common in the United States, where 83 percent of fact-checkers (35 of 42) are operated by or closely affiliated with bigger news organizations. In the rest of the world, a bit over half (44 of 84, or 52 percent) have direct news media ties. But that mix may be shifting. In our 2016 census, less than half of the fact-checkers outside the U.S. were part of a larger media house (24 of 55, or 44 percent).

If you’re keeping track of all these numbers, you better write them down in pencil and be ready for updates. We still have a pending list of other fact-checkers we need to evaluate, including some whose staff we look forward to meeting at the Madrid summit. (Here’s an explanation of how the Reporters’ Lab identifies the fact-checkers we include in our database. In addition to journalism that fairly examines the accuracy of statements by public figures and institutions, we also look for authoritative, nonpartisan reporting on the progress of political promises and the credibility of widely shared online sources of information and misinformation.)

The healthy growth we’ve measured since last year’s Global Fact conference comes even after we had to move more than a dozen other fact-checkers to inactive status. In fact, at this point we have a list of more than five dozen inactive fact-checking initiatives.

That kind of fluctuation and turnover is consistent with the natural attrition we’ve tracked over the past several years — with many fact-checkers springing up for campaigns and then going dark. Some election-oriented fact-checkers will reliably return for the next campaign. That requires us to continuously determine which projects are hibernating comfortably and which have met their ultimate fact-checking fate. But since we can now base those choices on several years of observation, we now leave these seasonal fact-checkers marked as “active” in our database, noting their campaign focus in our descriptions. And we are continuously finding established fact-checkers who previously escaped our notice, which also adds to the growing tally. If you’re one of them, please let us know.

The Reporters’ Lab is a project of the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy at Duke University’s Sanford School for Public Policy. We started the fact-checking database three years ago to track the reach and impact of this journalism. It also supports the Lab’s efforts to develop tools and services that help fact-checkers report and disseminate their work to a bigger audience. That includes Share the Facts, a project that helps fact-checkers distribute their reporting on other websites and platforms, including devices such as the Amazon Echo. Google also has used the Lab’s fact-checking database in its recent efforts to elevate fact-checks in search results and on the redesigned Google News page.

This update is based on research compiled over several months in part by Reporters’ Lab student researcher Hank Tucker. Alexios Mantzarlis of the Poynter Institute’s International Fact-Checking Network also contributed, as did Reporters’ Lab director Bill Adair, Knight Professor for the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke University (and founder of PolitiFact). Thanks also to Cristina Tardáguila of Agência Lupa in Brazil, Itziar Bernaola of El Objetivo in Spain, Boyoung Lim of Newstapa in South Korea, and many other fact-checkers around the world who help us keep up with this fast-growing form of journalism.

Please send updates and additions to Reporters’ Lab co-director Mark Stencel (mark.stencel@duke.edu).

Comments closed