Fact-checking triples over four years

The annual fact-checking census from the Reporters' Lab finds 31 percent growth in the past year alone, and signs that many verification projects are becoming more stable.

By Mark Stencel and Riley Griffin - February 22, 2018

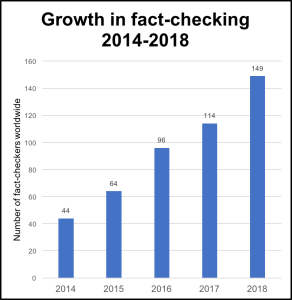

The number of fact-checkers around the world has more than tripled over the past four years, increasing from 44 to 149 since the Duke Reporters’ Lab first began counting these projects in 2014 — a 239 percent increase. And many of those fact-checkers in 53 countries are also showing considerable staying power.

This is the fifth time the Reporters’ Lab has tallied up the organizations where reporters and researchers verify statements by public figures and organizations and keep tabs on other sources of misinformation, particularly social media. In each annual census, we have seen steady increases on almost every continent — and the past year was no different.

The 2018 global count is up by nearly a third (31 percent) over the 114 projects we included in last year’s census. While some of that year-over-year change comes because we discovered established fact-checking ventures that we hadn’t yet counted in our past surveys, we also added 21 fact-checking projects that launched since the start of 2017, including one — Tempo’s “Fakta atau Hoax” in Indonesia — that opened for business a month ago.

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster NRK for Norway’s national election last year. That series is now among the 63 inactive fact-checkers we count on our regularly updated map, list and database. Faktisk, a Norwegian fact-checking partnership that several media companies launched in 2017, remains active.

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster NRK for Norway’s national election last year. That series is now among the 63 inactive fact-checkers we count on our regularly updated map, list and database. Faktisk, a Norwegian fact-checking partnership that several media companies launched in 2017, remains active.

Elections are often catalysts for political watchdog projects. In addition to the two Norwegian projects, national or regional voting helped spur new fact-checking efforts in Indonesia, South Korea, France, Germany and Chile.

Fact-Checkers By Continent

Africa:4

Asia: 22

Australia: 3

Europe : 52

North America: 53

South America: 15

Many of the fact-checkers we follow have shown remarkable longevity.

Based on the 143 projects whose launch dates we know for certain, 41 (29 percent) have been in business for more than five years. And a diverse group of six have already celebrated 10 years of nearly continuous operation — from 23-year-old Snopes.com, the grandparent of hoax-busting, to locally focused “Reality Checks” from WISC-TV (News 3) in Madison, Wisconsin, which started fact-checking political statements in 2004. Some long-term projects have occasionally shuttered between election cycles before resuming their work. And some overcame significant funding gaps to come back from the dead.

On average, fact-checking organizations have been around four years.

One change we have noted over the past few years is some shifting in the kind of organizations that are involved in fact-checking and the way they do business. The U.S. fact-checker PolitiFact, for instance, began as an independent project of the for-profit Tampa Bay Times in 2007. With its recently announced move to Poynter Institute, a media training center in St. Petersburg, Florida, that is also the Times’ owner, PolitiFact now has nonprofit status and is no longer directly affiliated with a larger news company.

That’s unusual move for a project in the U.S., where most fact-checkers (41 of 47, or 87 percent) are directly affiliated with newspapers, television networks and other established news outlets. The opposite is the case outside the U.S., where a little more than half of the fact-checkers are directly affiliated (54 of 102, or 53 percent).

The non-media fact-checkers include projects that are affiliated with universities, think tanks and non-partisan watchdogs focused on government accountability. Others are independent, standalone fact-checkers, including a mix of nonprofit and commercial operations as well as a few that are primarily run by volunteers.

Fact-checkers, like other media outlets, are also seeking new ways to stay afloat — from individual donations and membership programs to syndication plans and contract research services. Facebook has enlisted fact-checkers in five countries to help with the social platform’s sometimes bumpy effort to identify and label false information that pollutes its News Feed. (Facebook also is a Reporter’s Lab funder, we should note.) And our Lab’s Google-supported Share the Facts project helped that company elevate fact-checking on its news page and other platforms. That’s a development that creates larger audiences that are especially helpful to the big-media fact-checkers that depend heavily on digital ad revenue.

Growing Competition

The worldwide growth in fact-checking means more countries have multiple reporting teams keeping an ear out for claims that need their scrutiny.

Last year there were 11 countries with more than one active fact-checker. This year, we counted more than one fact-checker in 22 countries, and more than two in 11 countries.

Countries With More Than Two Fact-Checkers

United States: 47

Brazil: 8

France: 7

United Kingdom: 6

South Korea: 5

India: 4

Germany: 4

Ukraine: 4

Canada: 4

Italy: 3

Spain: 3

There’s also growing variety among the fact-checkers. Our database now includes several science fact-checkers, such as Climate Feedback at the University of California Merced’s Center for Climate Communication and Détecteur de Rumeurs from Agence Science-Presse in Montreal. Or there’s New York-based Gossip Cop, an entertainment news fact-checking site led since 2009 by a “reformed gossip columnist.” (Gossip Cop is also another example of a belated discovery that only appeared on our fact-checking radar in the past year.)

As the fact-checking community around the world has grown, so has the International Fact-Checking Network. Launched in 2015, it too is based at Poynter, the new nonprofit home of PolitiFact. The network has established a shared Code of Principles as well as a process for independent evaluators to verify its signatories’ compliance. So far, about a third of the fact-checkers counted in this census, 47 of 149, have been verified.

The IFCN also holds an annual conference for fact-checkers that is co-sponsored by the Reporters’ Lab. There is already a wait list of hundreds of people for this June’s gathering in Rome.

U.S. Fact-Checking

The United States still has far more fact-checkers than any other country, but growth in the U.S. was slower in 2017 than in the past. For the first time, we counted fewer fact-checkers in the United States (47) than there were in Europe (52).

While the U.S. count ticked up slightly from 43 a year ago, some of that increase came from the addition of newly added long-timers to our database — such as the Los Angeles Times, Newsweek magazine and the The Times-Union newspaper in Jacksonville, Florida. Another of those established additions was the first podcast in our database: “Science Vs.” But that was an import. “Science Vs.” began as a project at the Australian public broadcaster ABC in 2015 before it found its U.S. home a year later at Gimlet Media, a commercial podcasting company based in New York.

Among the new U.S. additions are two traditionally conservative media outlets: The Daily Caller (and its fact-checking offshoot Check Your Fact) and The Weekly Standard. To comply with the IFCN’s Code of Principles, both organizations have set up internal processes to insulate their fact-checkers from the reporting and commentary both publications are best known for.

Another new addition was the The Nevada Independent, a nonprofit news service that focuses on state politics. Of the 47 U.S. fact-checkers, 28 are regionally oriented, including the 11 state affiliates that partner with PolitiFact.

We originally expected the U.S. number would drop in a year between major elections, as we wrote in December, so the small uptick was a surprise. With this year’s upcoming midterm elections, we expect to see even more fact-checking in the U.S. in 2018.

The Reporters’ Lab is a project of the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy at Duke University’s Sanford School for Public Policy. It is led by journalism professor Bill Adair, who was also PolitiFact’s founding editor. The Lab’s staff and student researchers identify and evaluate fact-checkers that specifically focus on the accuracy of statements by public figures and institutions in ways that are fair, nonpartisan and transparent. See this explainer about how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the database. In addition to studying the reach and impact of fact-checking, the Lab is home to the Tech & Check Cooperative, a multi-institutional project to develop automated reporting tools and applications that help fact-checkers spread their work to larger audiences more quickly.

Pop-up fact-checking app Truth Goggles aims to challenge readers’ biases

Created by Dan Schultz, Truth Goggles is a browser plugin that creates a personalized "credibility layer" for users

By Julianna Rennie - February 21, 2018

Dan Schultz, a technologist building a new fact-checking app for the Reporters’ Lab, says the app should be like a drinking buddy.

“You can have a friend who you fundamentally disagree with on a lot of things, but are able to have a conversation,” Schultz says. “You’re not thinking of the other person as a spiteful jerk who’s trying to manipulate you.”

Schultz, 31, is using that approach to develop a new version of Truth Goggles, an app he first built eight years ago at the MIT Media Lab, for the Duke Tech & Check Cooperative. His goal is to get to know users and find the most effective way to show them fact-checks. While other Tech & Check apps take a traditional approach by providing Truth-O-Meter ratings or Pinocchios to all users, Schultz plans to experiment with customized formats. He hopes that personalizing the interface will attract new audiences who are put off by fact-checkers’ rating systems.

Truth Goggles is a browser plugin that automatically scans a page for content that users might want fact-checked. Schultz hopes that this unique “credibility layer” will be like a gentle nudge to get people to consider fact-checks.

“The goal is to help people think more carefully and ideally walk away with a more accurate worldview from their informational experiences,” he says.

As a graduate student at the Media Lab, Schultz examined how people interact with media. His 150-page thesis paper concluded that when people are consuming information, they are protecting their identities.

Schultz learned that a range of biases make people less likely to change their minds when exposed to new information. Most people simply are unaware of how to consume online content responsibly, he says.

He then set out to use technology to short-circuit biased behavior and help people critically engage with media. The first prototype of Truth Goggles used fact-checks from PolitiFact as a data source to screen questionable claims.

“The world will fall apart if we don’t improve the way information is consumed through technology.”

Schultz recently partnered with the Reporters’ Lab to resume working on Truth Goggles. This time, Truth Goggles will be integrated with Share the Facts, so it can access all fact-checking articles formatted using the ClaimReview schema.

Schultz also is exploring creative ways to present the information to users. He says the interface must be effective in impeding biases and enjoyable for people to use. As a graduate student, one of Schultz’s initial ideas was to highlight verified claims in green and falsehoods in red. But he quickly realized this solution was not nuanced enough.

“I don’t want people to believe something’s true because it’s green,” he says.

The new version of Truth Goggles will use information about users’ biases to craft messages that won’t trigger their defenses. But Schultz doesn’t know exactly what this will look like yet.

“Can we use interfaces to have a reader challenge their beliefs in ways that just a blunt presentation of information wouldn’t?” Schultz says. “If the medium is the message, how can we shape the way that message is received?”

Born in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania, Schultz studied information systems, computer science and math at Carnegie Mellon University. As a sophomore, he won the Knight News Challenge, which provides grants for “breakthrough ideas in news and information.”

The News Challenge put him “on the path toward eventually applying to the Media Lab and really digging in,” he says.

After graduating from MIT, Schultz worked as a Knight-Mozilla Fellow at the Boston Globe and then joined the Internet Archive, where his title is senior creative technologist. He continues to develop side projects such as Truth Goggles through the Bad Idea Factory, a company with a tongue-in-cheek name that he started with friends. He says the company’s goal is “to make people ‘thinking face’ emoji” by encouraging its technologists to try out creative ideas. With Truth Goggles, he hopes to get people who may not already consume fact-checking content to challenge their own biases.

“The world will fall apart if we don’t improve the way information is consumed through technology,” Schultz says. “It’s sort of like the future of the universe as we know it depends on solving some of these problems.”

What we learned during our experiment with live fact-checking

We got some nice feedback and helpful suggestions about FactStream, our new app

By Bill Adair - February 1, 2018

Except for the moment when we almost published an article about comedian Kevin Hart’s plans for his wedding anniversary, the first test of FactStream, our live fact-checking app, went remarkably smoothly.

FactStream is the first in a series of apps we’re building as part of our Tech & Check Cooperative. We conducted a beta test during Tuesday’s State of the Union address that provided instant analysis from FactCheck.org, PolitiFact and Glenn Kessler, the Washington Post Fact Checker.

Overall, the app functioned quite well. Our users got 32 fact-checks during the speech and the Democratic response. Some were links to previously published checks while others were “quick takes” that briefly explained the relative accuracy of Trump’s claim.

When President Trump said “we enacted the biggest tax cuts and reforms in American history,” users got nearly instant assessments from FactCheck and PolitiFact.

When President Trump said “we enacted the biggest tax cuts and reforms in American history,” users got nearly instant assessments from FactCheck and PolitiFact.

“It is not the biggest tax cut,” said the quick take from FactCheck.org. “It is the 8th largest cut since 1918 as a percentage of gross domestic product and the 4th largest in inflation-adjusted dollars.”

PolitiFact’s post showed a “False” Truth-O-Meter and linked to an October fact-check of a nearly identical claim by Trump. Users of the app could click through to read the October check.

Many of the checks appeared on FactStream seconds after Trump made a statement. That was possible because fact-checkers had an advance copy of the speech and could compose their checks ahead of time.

We had two technical glitches – and unfortunately both affected Glenn. One was a mismatch of the URLs for published Washington Post fact-checks that were in our database, which made it difficult for him to post links to his previous work. We understand the problem and will fix it.

The other glitch was bizarre. Last year we had a hiccup in our Share the Facts database that affected only a handful of our fact-checks. But during Tuesday’s speech we happened to hit one when Glenn got an inadvertent match with an article from the Hollywood rumor site Gossip Cop, another Share the Facts partner. So when he entered the correct URL for his own article about Trump’s tax cut, a fact-check showed up on his screen that said “Kevin Hart and Eniko Parrish’s anniversary plans were made up to exploit the rumors he cheated.”

Oops!

Fortunately Glenn noticed the problem and didn’t publish. (Needless to say, we’re fixing that bug, too.)

This version of FactStream is the first of several we’ll be building for mobile devices and televisions. This one relies on the fact-checkers to listen for claims and then write short updates or post links to previous work. We plan to develop future versions that will be automated with voice detection and high-speed matching to previous checks.

This version of FactStream is the first of several we’ll be building for mobile devices and televisions. This one relies on the fact-checkers to listen for claims and then write short updates or post links to previous work. We plan to develop future versions that will be automated with voice detection and high-speed matching to previous checks.

We had about 3,100 people open FactStream over the course of the evening. At the high point we had 1,035 concurrently connected users.

Our team had finished our bug testing and submitted a final version to Apple less than 48 hours before the speech, so we were nervous about the possibility of big crashes. But we watched our dashboard, which monitored the app like a patient in the ICU, and saw that it performed well.

Our goal for our State of the Union test was simple. We wanted to let fact-checkers compose their own checks and see how users liked the app. We invited users to fill out a short form or email us with their feedback.

The response was quite positive. “I loved it — it was timely in getting ‘facts’ out, easy to use, and informative!” Also: “I loved FactStream! I was impressed by how many fact-checks appeared and that all of them were relevant.”

We also got some helpful complaints and suggestions:

Was the app powered by people or an algorithm? We didn’t tell our users who was choosing the claims and writing the “quick takes,” so some people mistakenly thought it was fully automated. We’ll probably add an “About” page in the next version.

More detail for Quick Takes. Users liked when fact-checkers displayed a rating or conclusion on our main “stream” page, which happened when they had a link to a previous article. But when the fact-checkers chose instead to write a quick take, we showed nothing on the stream page except the quote being checked. Several people said they’d like some indication about whether the statement was true, false or somewhere in between. So we’ll explore putting a short headline or some other signal about what the quick take says.

Better notifications. Several users said they would like the option of getting notifications of new fact-checks when they weren’t using the app or had navigated to a different app or website. We’re going to explore how we might do that, recognizing that some people may not want 32 notifications for a single speech.

An indication the app is still live. There were lulls in the speech when there were no factual claims, so the fact-checkers didn’t have anything new to put on the app. But that left some users wondering if the app was still working. We’ll explore ways we can indicate that the app is functioning properly.

What to expect tonight from FactStream, our live fact-checking app

It’s an early step toward automated fact-checking. What could go wrong?

By Bill Adair - January 30, 2018

Tonight we’re conducting a big test of automated fact-checking. Users around the world will be able to get live fact-checks from the Washington Post, PolitiFact and FactCheck.org on our new FactStream app.

It’s an ambitious experiment that was assembled with unusual speed. Our team – lead developer Christopher Guess, project manager Erica Ryan and the designers from the Durham firm Registered Creative – built the app in just three months. We were still testing the app for bugs as recently as Sunday night (we found a couple and have fixed them!).

FactStream, part of the Duke Tech & Check Cooperative, is our name for apps that provide live fact-checking. This first version will rely on the fact-checkers to identify claims and then push out notifications. Future versions will be more automated.

We’re calling tonight’s effort a beta test because it will be the first time we’ve used the app for a live event. We’ve tested it thoroughly over the past month, but it’s possible (likely?) we could have some glitches. Some things that might happen:

- President Trump might make only a few factual claims in the speech. That could mean you see relatively few fact-checks.

- Technical problems with the app. We’ve spent many hours debugging the app, fixing problems that ranged from a scrolling glitch on the iPhone SE to a problem we called “the sleepy bug” that caused the app to stop refreshing. We think we’ve fixed them all. But we can’t be sure.

- Time zone problems. If you set an alert for tonight’s speech before we fixed a time zone bug this morning, you got a notification at 3 p.m. Eastern time today that said “2018 State of the Union Address will begin in fifteen minutes.” Um, no, it’s at 9 p.m. Eastern tonight. But we believe we’ve fixed the bug!

(I’m writing this at the suggestion of Reporters’ Lab co-director Mark Stencel, who notes that Elon Musk has highlighted video of his rockets exploding to make the point that tests can fail.)

Long road to reusabity of Falcon 9 primary boost stage…When upper stage & fairing also reusable, costs will drop by a factor >100. pic.twitter.com/WyTAQ3T9EP

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) September 14, 2017

The future of fact-checking is here. Our goal tonight is to test the app and explore the future of automated journalism. We’re excited to try – even if we encounter a few problems along the way.

I hope you’ll try the app and let us know what you think. You can email us at team@sharethefacts.org or use this feedback form.

Want to help us test our fact-checking app during the State of the Union?

The FactStream app provides live fact-checking during political events. We’d like your help testing it during the speech.

By Rebecca Iannucci - January 26, 2018

The Duke Reporters’ Lab is seeking beta testers for FactStream, our new second-screen app that will provide live fact-checking during political events.

On Tuesday, Jan. 30, the Reporters’ Lab will partner with PolitiFact, The Washington Post and FactCheck.org, which will provide FactStream users with live fact-checking of President Trump’s State of the Union address.

Throughout the speech, FactStream users will see pop-ups on their screen, alerting them to previously published fact-checks or real-time analyses of President Trump’s claims. By pressing on a pop-up, users can read the full text of a fact-check, share the fact-check on various social media platforms or simply receive additional context about Trump’s statements.

Throughout the speech, FactStream users will see pop-ups on their screen, alerting them to previously published fact-checks or real-time analyses of President Trump’s claims. By pressing on a pop-up, users can read the full text of a fact-check, share the fact-check on various social media platforms or simply receive additional context about Trump’s statements.

FactStream is a product of the Duke Tech & Check Cooperative, a $1.2 million effort that uses automation to help fact-checkers do their work and broaden their audience. Launched in September 2017, Tech & Check also serves as a hub to connect journalists, researchers and computer scientists who are doing similar work.

The first iteration of FactStream is a manual app that requires the work of human fact-checkers behind the scenes. It is an important first step toward the “holy grail” of fact-checking — automated detection of a claim that is instantly matched to a published fact-check.

If you are an iPhone or iPad user and would like to test FactStream during the State of the Union, here’s how:

(1) Download FactStream from the App Store.

(2) Open and use the app during President Trump’s speech (Jan. 30 at 9 p.m. ET), making sure to test the app’s various screens and shared fact-checks.

(3) After the speech is over, send us feedback about the app with this Google Form.

Bloomberg editor discusses Greek life at Duke, new book on the hazards of fraternities

In a lecture at Duke University, author John Hechinger explores the uncertain future of Greek life on college campuses

By Riley Griffin - January 25, 2018

“Insurance companies have rated fraternities just above toxic waste.”

John Hechinger, a senior editor at Bloomberg News, addressed a room of Greek-affiliated and unaffiliated Duke undergraduates on Jan. 23, devoting a portion of his lecture to the issue of liability insurance within fraternities.

“You should know this,” he said solemnly. “Students are taking the liability on themselves. You’re likely to be named if someone dies.”

In September 2017, Hechinger published True Gentlemen: The Broken Pledge of America’s Fraternities, an exposé of American fraternity life. The book offers a deep dive on Sigma Alpha Epsilon, a historically white fraternity that has made headlines for sexual assault, racism and alcohol-induced deaths during hazing.

“There had never been an African-American member of SAE, and I wanted to explore that,” Hechinger said during a discussion provocatively titled, “Can Fraternities Be Saved? Can They Save Themselves?”

“Turns out at the University of Alabama, there are a whole bunch of fraternities… none of them have ever had African-American members,” he continued.

Hechinger said the lack of diversity that exists among historically white fraternities can be seen on Duke’s own campus.

“It’s an extreme example of what the Duke Chronicle is now writing about,” he said, referencing a Jan. 19 article that examined socioeconomic and geographic diversity within Duke fraternities and sororities.

But Hechinger said Duke’s Greek system is still very different from those at other universities. He identified Duke’s efforts to delay rush until the spring semester of each school year and bolster non-Greek social organizations, such as Selected Living Groups, as successful ways to create a safer campus environment.

“I think Duke does a lot of things right,” he said.

One student asked Hechinger how Duke administrators could be more transparent about fraternities. “It takes exposure to force an organization to change,” he responded. “I’d like to see all the reports of sexual assault disclosed and mapped so you can see where they happen… and know the demographics, too.”

Although national fraternities have been thrust into the limelight over scandal and death, Hechinger said fraternities are more popular than ever.

“They are popular for a reason,” Hechinger said. “People really find value in them. Research shows that people who belong to fraternities believe they’ve had a better college experience and have a better sense of well-being.”

“They are popular for a reason,” Hechinger said. “People really find value in them. Research shows that people who belong to fraternities believe they’ve had a better college experience and have a better sense of well-being.”

Hechinger also said fraternities provide members with powerful networks upon graduation.

Fraternity men tend to earn higher salaries after college than non-fraternity men with higher GPAs, according to Bloomberg News. They also dominate business and politics. Fraternity members make up about 76 percent of U.S. senators, 85 percent of Supreme Court justices and 85 percent of Fortune 500 executives, according to The Atlantic.

“That’s a testament to the power of networking,” Hechinger said.

For this reason, universities and fraternities have a tenuous relationship. “They infuriate, yet need, each other,” Hechinger writes in his book. “College administrators who try to crack down on fraternity misbehavior often find themselves confronting an influential, well-financed and politically connected adversary.”

Hechinger concluded his lecture by advocating for institutional change.

“If fraternities grapple with these issues, particularly the diversity issue, I think they do have a future,” he said. “I hope they focus more on values of brotherhood.”

New Tech & Check projects will provide pop-up fact-checking

With advances in artificial intelligence and the growing use of the ClaimReview schema, Reporters' Lab researchers are developing a new family of apps that will make pop-up fact-checking a reality

By Julianna Rennie - January 16, 2018

For years, fact-checkers have been working to develop automated “pop-up” fact-checking. The technology would enable users to watch a political speech or a campaign debate while fact-checks pop onto their screens in real time.

That has always seemed like a distant dream. A 2015 report on “The Quest to Automate Fact-Checking” called that innovation “the Holy Grail” but said it “may remain far beyond our reach for many, many years to come.”

Since then, computer scientists and journalists have made tremendous progress and are inching closer to the Holy Grail. Here in the Reporters’ Lab, we’ve received $1.2 million in grants to make automated fact-checking a reality.

The Duke Tech & Check Cooperative, funded by Knight Foundation, the Facebook Journalism Project and the Craig Newmark Foundation, is an effort to use automation to help fact-checkers research factual claims and broaden the audience for their work. The project will include about a half-dozen pop-up apps that will provide fact-checking on smartphones, tablets and televisions.

One key to the pop-up apps is a uniform format for fact-checks called the ClaimReview schema. Developed through a partnership of Schema.org, the Reporters’ Lab, Jigsaw and Google, it provides a standard tagging system for fact-checking articles that makes it easier for search engines and apps to identify the details of a fact-check. ClaimReview, which can be created using the Share the Facts widget developed by the Reporters’ Lab, will enable future apps to quickly find relevant fact-checking articles.

“Now, I don’t need to scrape 10 different sources and try to wrangle permission because there’s this database that will be growing increasingly,” says Dan Schultz, senior creative technologist at the Internet Archive.

This works because politicians repeat themselves. For example, many politicians and analysts have claimed that the United States has the highest corporate tax rate.

The Reporters’ Lab is developing several pop-up apps that will deliver fact-checking in real time. The apps will include:

The Reporters’ Lab is developing several pop-up apps that will deliver fact-checking in real time. The apps will include:

- FactStream, which will display relevant fact-checks on mobile devices during a live event. The first version, to be tested this month during the State of the Union address Jan. 30, will be a “manual” version that will rely on fact-checkers. When they hear a claim that they’ve checked before, the fact-checkers will compose a message containing the URL of the fact-check or a brief note about the claim. That message will appear in the FactStream app on a phone or tablet.

- FactStream TV, which will use platforms such as Chromecast or Apple TV for similar pop-up apps on television. The initial versions will also be manual, enabling fact-checkers to trigger the notifications.

Another project, Truth Goggles, will be a plug-in for a web browser that will automatically scan a page for content that users should think about more carefully. Schultz, who developed a prototype of Truth Goggles as a grad student at the MIT Media Lab, will use the app to experiment with different ways to present accurate information and help determine which methods are most valuable for readers.

The second phase of the pop-up apps will take the human fact-checker out of the equation. For live events, the apps will rely on voice-to-text software and then match with the database of articles marked with ClaimReview.

The future apps will also need natural language processing (NLP) abilities. This is perhaps the biggest challenge because NLP is necessary to reflect the complexities of the English language.

“Human brains are very good at [NLP], and we’re pretty much the only ones,” says Chris Guess, the Reporters’ Lab’s chief technologist for Share the Facts and the Tech & Check Co-op. Programming a computer to understand negation or doublespeak, for instance, is extremely difficult.

Another challenge comes from the fact that there are few published fact-checks relative to all of the claims made in conversation or articles. “The likelihood of getting a match to the 10,000 or so stored fact-checks will be low,” says Bill Adair, director of the Reporters’ Lab.

Ideally, computers will eventually research and write the fact checks, too. “The ultimate goal would be that it could pull various pieces of information out, use that context awareness to do its own research into various data pools across the world, and create unique and new fact-checks,” Guess says.

The Reporters’ Lab is also developing tools that can help human fact-checkers. The first such tool uses ClaimBuster, an algorithm that can find claims fact-checkers might want to examine, to scan transcripts of newscasts and public events and identify checkable claims.

“These are really hard challenges,” Schultz says. “But there are ways to come up with creative ways around them.”

A big year for fact-checking, but not for new U.S. fact-checkers

Following a historic pattern, the number of American media outlets verifying political statements dropped after last year's presidential campaign.

By Mark Stencel - December 13, 2017

All the talk about political lies and misinformation since last year’s election has been good for the fact-checking business in the United States — but it has not meant an increase in fact-checkers. In fact, the number has dropped, much as we’ve come to expect during odd-numbered years in the United States.

We’re still editing and adding to our global list of fact-checkers for the annual census we’ll publish in January. Check back with us then for the final tally. But the trend line in the United States already is following a pattern we’ve seen before in the year after a presidential election: At the start of 2017, there were 51 active U.S. fact checkers, 35 of which were locally oriented and 16 of which were nationally focused. Now there are 44, of which 28 are local and 16 are mainly national.

This count includes some political fact-checkers that are mainly seasonal players. These news organizations have consistently fact-checked politicians’ statements through political campaigns, but then do little if any work verifying during the electoral “offseason.” And not all the U.S. fact-checkers in our database focus exclusively — or even at all — on politics. Sites such as Gossip Cop, Snopes.com and Climate Feedback are in the mix, too.

The story is different elsewhere in the world, where we have seen continuing growth in the number of fact-checking ventures, especially in countries that held elections and weathered national political scandals. Again, our global census isn’t done yet, but so far we’ve counted 137 active fact-checking projects around the world — up from 114 at the start of the year. And we expect more to come — offsetting the number of international fact-checkers that closed down in other countries after the preceding year’s elections.

Still, the number of U.S. fact-checkers accounts for about a third of the projects that appear in the Reporters’ Lab’s database, even after this year’s drop.

So why do so many U.S. fact-checkers close up shop after elections? PolitiFact founder Bill Adair, who now runs the Reporters’ Lab and Duke’s DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy, asked that question in a New York Times op-ed on the eve of last year’s election. He attributed the retraction in part to the fact-checkers’ traditional focus on claims made in political ads, which was how the movement began in the early 1990s. Also, newsroom staffing and budgets often shrink after the votes are counted. That’s too bad, because, as Bill noted, “politicians don’t stop lying on Election Day.”

A handful of U.S. newcomers began fact-checking in 2017. One was Indy Fact Check. It’s a project of The Nevada Independent, a nonprofit news site based in Las Vegas. The Independent got its feet wet in January with a look at the accuracy of Gov. Brian Sandoval’s 2017 State of the State address before launching a regular fact-checking series in June.

To rate the claims it reports on, Indy Fact Check uses a sliding, true-to-false scale illustrated with cartoon versions of Abraham Lincoln. The facial expression on “Honest Abe” changes with each rating, which run from “Honest as Abe” and “Almost Abe” on the true side to “Hardly Abe” and “All Hat, no Abe” on the false side.

One of Indy Fact Check’s regular contributors is Riley Snyder, who previously was the reporter at PolitiFact Nevada at KTNV-TV (13 Action News). KTNV was one of several local news outlets owned by Scripps TV Station Group that briefly served as PolitiFact state affiliates before closing down the partnership — after the 2016 election, of course. So in Nevada at least, one site closes and another opens.

Another new player in the U.S. fact-checking market this year was The Weekly Standard. This conservative publication based in Washington has a dedicated fact-checker, Holmes Lybrand, who does not contribute to the political commentary and reporting for which the Standard is generally known. With this structural separation, it recently became a verified signatory of the International Fact-Checking Network’s code of principles. The Standard is owned by Clarity Media Group, a division of the Anschutz Entertainment Group that also publishes the Washington Examiner and Red Alert Politics.

By January, we may have a few more additions to add to our 2017 tally, but that won’t change the bottom line. This was a year of retraction in the U.S. That’s similar to the pattern our database shows after the last presidential election, in 2013, when PunditFact was the only new U.S. fact-checker.

But the numbers began to grow again a year later, during the midterm election in 2014, and continued from there. Because of the large number of candidates and the early start of the 2016 presidential debate and primary process, a number of new fact-checkers launched in 2015. So we’ll be watching for similar patterns in the United States over the next two years.

Student researcher Riley Griffin contributed to this report.

The wide world of fact-checking apps

From phone apps to browser extensions, the landscape of fact-checking tools is growing — but how many of them are useful?

By Bill McCarthy - December 6, 2017

It is no secret that news consumers are finding it increasingly difficult to separate fact from fiction, especially when it comes to politics.

Sure, they can visit journalism’s traditional truth-seeking outlets — such as PolitiFact or FactCheck.org — if they are looking for the whole story. But what if they want a quicker fix? What if they want to know, with the click of a button, if the article they are reading may include fabricated content? Well, there may now be an app for that — in fact, many apps.

The wave of falsehoods that dominated the 2016 election cycle has inspired several enterprising companies and individuals to create mobile applications and web browser extensions to promote fact-checking and detect stories with falsehoods.

In a recent analysis for the Reporters’ Lab, I identified at least 45 fact-checking and falsehood-detecting apps and browser extensions available for download on the Apple or Android app stores, the Google Chrome web store and Firefox. Many share similar design characteristics and functionality.

Several of the best apps and extensions simply make fact-checks more accessible. These apps, including Settle It! Politifact’s Argument Ender, let users view and filter through fact-checks aggregated from online fact-checking sites. (Disclosure: Bill Adair, director of the Reporters’ Lab, contributed to the creation of this app.) Some, like The Washington Post’s RealDonaldContext, are specifically tailored to fact-check President Donald Trump’s tweets.

A few extensions — such as FakerFact or NewsCracker — evaluate credibility online by generating algorithmic scores to predict whether particular web pages are likely true or false. I found both extensions questionable because it is not clear which inputs are driving their algorithms. But they show nonetheless that fully automated fact-checking may not be so far away — even if FakerFact and NewsCracker are themselves lacking in transparency and value.

Other extensions enable users to crowdsource fact-checks. Users of these community-oriented platforms can flag and provide fact-checks online for other users to see. Where these extensions fail, however, is in training their users to fact-check. My analysis noted that several users have submitted fact-checks for opinion statements — and several others have disputed statements on a hyper-partisan basis.

Many of the existing apps and extensions are designed to spot, detect or block false stories. Some alert readers to any potential “bias” associated with a website, while others flag websites that may contain falsehoods, conspiracy theories, clickbait, satire and more. Some even provide security checks for spear phishing and malware. One drawback to these apps and extensions, however, is that their assessments are subjective — because all such apps and extensions are discretionary, none can honestly claim to be the end-all arbiter of truth or political bias.

In summary, some of the identified apps and extensions — like FactPopUp, our own Reporters’ Lab app that provides automated fact-checks to users watching the live stream of a political event — show signs of being on the cutting edge of fact-checking. The future is certainly bright. But not all of the market’s apps and extensions are highly effective in their current form.

Fact-checking and falsehood detection apps and extensions should be considered supplements to — not replacements of — human brain power. Given that caveat, below are three of what I found to be the most refined options. They are ready for action as news-reading supplements.

GlennKessler

GlennKessler, available for free download on Apple’s app store, is an aggregation of fact-checks from Glenn Kessler of The Washington Post’s Fact Checker. Kessler’s son, Hugo, created the app when he was 16 years old.

Users of GlennKessler can view fact-checked claims and filter them according to the number of “Pinocchios” they received or the political party of the speakers. The app also includes videos related to fact-checking and interviews with Glenn Kessler, as well as a game where users can test their fact-checking knowledge. As an added feature, users can learn about and email questions directly to Kessler himself.

Official Media Bias Fact Check Icon

![]()

The Official Media Bias Fact Check Icon, a free extension for Chrome browsers, purports to provide “bias” ratings for more than 2,000 media sources online. While browsing the internet, users are presented with a color-coded icon denoting each website’s “bias.”

A related extension, the Official Media Bias Fact Check Extension, highlights “bias” within Facebook’s news feed. Users can ask the extension to eliminate sources fitting a particular “bias” rating from appearing in their feed. Unfortunately, this “collapse” feature brings with it the possibility that users will abuse the extension to reinforce existing filter bubbles within an increasingly fragmented social media landscape.

It is important to remember as well that Media Bias Fact Check claims to find “bias” according to its own labeling methodology. This is a complicated assessment, so users should take the ratings with a grain of salt. As committed as a site may be to the truth, there can truly be no definitive rating for something so sensitive as political bias.

ZenMate SafeSearch and Fake News Detector

ZenMate SafeSearch and Fake News Detector, a free extension for Chrome browsers from the Berlin-based startup ZenMate, signals whether a website is “good” or “suspect.” Users see ratings not only of a website’s credibility, but also of its security and ownership. The extension does not work for articles appearing on social media.

Per the extension’s description, ZenMate SafeSearch “aggregates and enriches various databases and feeds” in order to assess the credibility of various webpages. I found this low level of transparency alarming. As with Media Bias Fact Check’s extensions, users should be wary that ZenMate’s ratings are by nature subjective. The concept of “bias” is likely more complicated for an algorithm to score.

Web Annotation presents a new way to break down the news

News organizations are getting creative to break down primary sources in a way people love

By Mark Stencel - December 1, 2017

When NPR used a new web annotation tool to live-annotate and fact-check the first presidential debate in 2016, the site brought in record traffic, with 7,413,000 pageviews from 6,011,000 users; 22 percent of visitors stayed all the way to the end, something worth noting in an era when quick, shareable information dominates the news.

“We think that people were coming for the transcript and then getting the annotation, which we were fine with,” joked David Eads during an interview with the Duke Reporters’ Lab. Eads was part of the NPR visuals team throughout the annotation project, and now works as a news applications developer at ProPublica Illinois. He held that skimming through long documents and transcripts, as opposed to reading excerpts or summaries of what people said, is the new way that people like to get their news and information online, hence why NPR’s monster of a debate transcript was so popular.

Whether or not that’s true, the success that some new web annotation tools have recently had when used by major newspaper companies is something to which we should pay attention. NPR’s live transcript was one example. Another is Genius, which started out as a website called Rap Genius that allows users to annotate the lyrics to rap songs, and has since expanded to include an annotation tool that’s being utilized consistently by The Washington Post. Every speech, statement or debate transcript published in an article on the Post gets annotated by a handful of journalists via the Genius sidebar, and this has clearly been working. According to Poynter, “engaged time on posts annotated using Genius are generally between three and four times better than a normal article.”

It makes sense that consumers would want to read original statements and primary sources, given current skepticism of the media and allegations being thrown around by politicians and social media bots. Web annotation provides journalists with a tool that allows them to be present while readers go through these documents, not to push an agenda or argument, but to provide expert context, analysis and background for their audience.

Web annotation may be limited in what it allows journalists to actually do; The Washington Post mostly only uses it to make it easier for journalists to comment on speeches and statements. But other organizations have gotten creative with their own annotation tools, like The New York Times, which annotated the U.S. Constitution, and FiveThirtyEight, which wrote annotated “Perfect Presidential Stump Speeches” for both Republicans and Democrats. And many of them, including Vox and The Atlantic, are utilizing web annotation in different styles and formats for the same purpose as The Washington Post: a tool their journalists can use to break down speeches and debate transcripts into something more digestible, whole, and transparent for readers.

The first few attempts at all-powerful web annotation programs similar to Genius were epic failures. Third Voice was a browser plug-in created by a team of Singaporean engineers in 1998 that allowed users to annotate anything on any website. hough it showed promise in fostering intellectual conversation on tense topics online, it couldn’t shake its reputation of being a destructive method of Internet graffiti. A few years later in 2009, Google came up with Google Sidewiki that essentially did the same thing and encountered similar problems, as well as complications with advertisements and user communities. It lasted two years.

It’s no surprise that when you give the greater online community proverbial markers with which to annotate the entire internet, things go badly. It essentially becomes another YouTube comment section in which people can say and do whatever they want — except they can do it directly on top of a paragraph in a news article, which horrified many website owners.

But when the power to annotate is given to an expert (such as David Victor, co-chair of the Brookings Initiative on Energy and Climate and global policy professor at the University of California San Diego), in a specific setting (such as Trump’s Paris Climate Agreement speech, posted on Vox), the resulting article is an archive of knowledge and information that allows readers to know not only exactly what was said, but also what it really meant and why it matters.

An old example of annotation that I did find interesting to look back on was the first-ever instance of something being annotated: Martin Gardner’s Annotated Alice. Gardner was apparently frustrated by how much of Lewis Carroll’s clever genius was being missed in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, as many of the witty jokes Carroll made were strict references to Oxford and to the Liddell family (whose daughter Alice inspired the novel). In the introduction of The Annotated Alice, Gardner remarks that “in the case of Alice we are dealing with a very curious, complicated kind of nonsense, written for British readers of another century, and we need to know a great many things that are not a part of the text if we wish to capture its full wit and flavor.”

If you ask me, “a curious, complicated kind of nonsense” also sounds like an appropriate way to describe most of today’s political discourse. American citizens don’t know how to tell what is true and what is false, what is being exaggerated or made up, and what agendas these claims are trying to serve. And with social media setting such a complicated, manipulated stage for information to spread, it’s becoming increasingly harder to objectively assess the news.

Web annotation isn’t the answer to all of these problems, but it’s a nice way to start breaking down the primary sources, original statements and speech and debate transcripts. When used carefully, as NPR and The Washington Post have proved is possible, it allows journalists to present information in a transparent, natural way. The role of a journalist is, after all, to present complicated, sometimes nonsensical happenings in a way that an audience can understand, and if there’s a way to make that education easier and more entertaining, it should be welcomed.