With the U.S. election now less than a year away, at least four-dozen American fact-checking projects plan to keep tabs on claims by candidates and their supporters – and a majority of those fact-checkers won’t be focused on the presidential campaign.

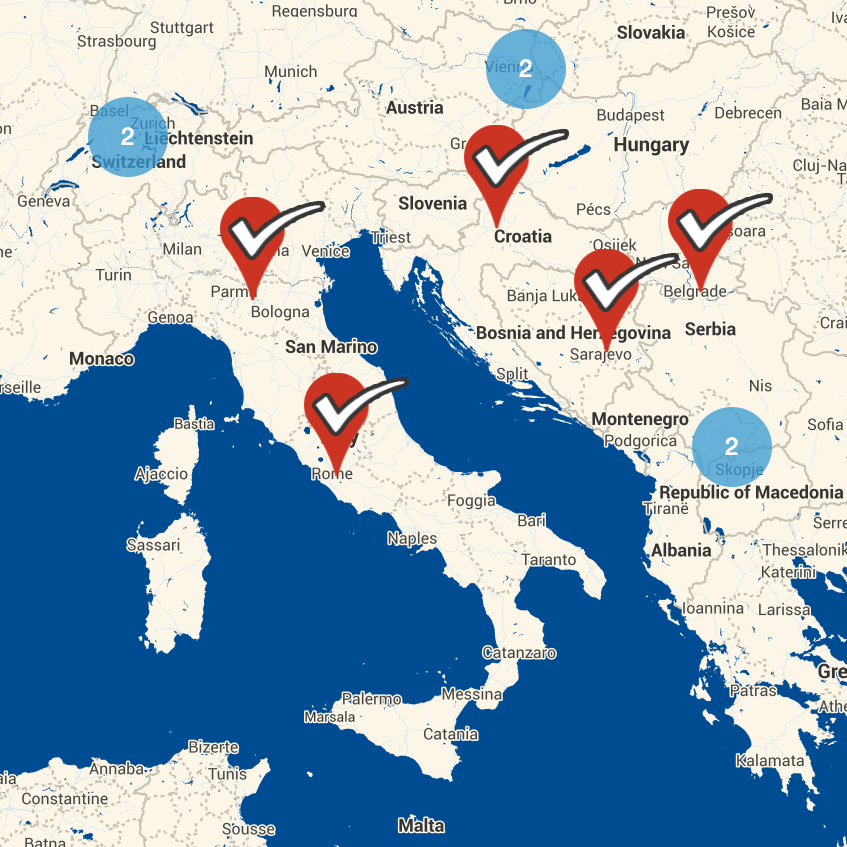

The 50 active U.S. fact-checking projects are included in the latest Reporters’ Lab tally of global fact-checking, which now shows 226 sites in 73 countries. More details about the global growth below.

Of the 50 U.S. projects, about a third (16) are nationally focused. That includes independent fact-checkers such as FactCheck.org, PolitiFact and Snopes, as well as major news media efforts, including the Associated Press, The Washington Post, CNN and The New York Times. There also are a handful of fact-checkers that are less politically focused. They concentrate on global misinformation or specific topic areas, from science to gossip.

At least 31 others are state and locally minded fact-checkers spread across 20 states. Of that 31, 11 are PolitiFact’s state-level media partners. A new addition to that group is WRAL-TV in North Carolina — a commercial TV station that took over the PolitiFact franchise in its state from The News & Observer, a McClatchy-owned newspaper based in Raleigh. Beyond North Carolina, PolitiFact has active local affiliates in California, Florida, Illinois, Missouri, New York, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

The News & Observer has not abandoned fact-checking. It launched a new statewide initiative of its own — this time without PolitiFact’s trademarked Truth-O-Meter or a similar rating system for the statements it checks. “We’ll provide a highly informed assessment about the relative truth of the claims, rather than a static rating or ranking,” The N&O’s editors said in an article announcing its new project.

Among the 20 U.S. state and local fact-checkers that are not PolitiFact partners, at least 13 use some kind of rating system.

Of all the state and local fact-checkers, 11 are affiliated with TV stations — like WRAL, which had its own fact-checking service before it joined forces with PolitiFact this month. Another 11 are affiliated with newspapers or magazines. Five are local digital media startups and two are public radio stations. There are also a handful of projects based in academic journalism programs.

One example of a local digital startup is Mississippi Today, a non-profit state news service that launched a fact-checking page for last year’s election. It is among the projects we have added to our database over the past month.

We should note that some of these fact-checkers hibernate between election cycles. These seasonal fact-checkers that have long track records over multiple election cycles remain active in our database. Some have done this kind of reporting for years. For instance, WISC-TV in Madison, Wisconsin, has been fact-checking since 2004 — three years before PolitiFact, The Washington Post and AP got into the business.

One of the hardest fact-checking efforts for us to quantify is run by corporate media giant TEGNA Inc. which operates nearly 50 stations across the country. Its “Verify” segments began as a pilot project at WFAA-TV in the Dallas area in 2016. Now each station produces its own versions for its local TV and online audience. The topics are usually suggested by viewers, with local reporters often fact-checking political statements or debunking local hoaxes and rumors.

A reporter at WCNC-TV in Charlotte, North Carolina, also produces national segments that are distributed for use by any of the company’s other stations. We’ve added TEGNA’s “Verify” to our database as a single entry, but we may also add individual stations as we determine which ones do the kind of fact-checking we are trying to count. (Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include.)

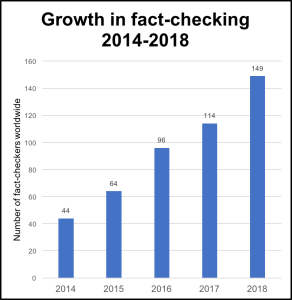

A Global Movement

As for the global picture, the Reporters’ Lab is now up to 226 active fact-checking projects around the world — up from 210 in October, when our count went over 200 for the first time. That is more than five times the number we first counted in 2014. It’s also more than double a retroactive count for that same year –- a number that was based on the actual start dates of all the fact-checking projects we’ve added to the database over the past five years (see footnote to our most recent annual census for details).

The growth of Agence France-Presse’s work as part of Facebook’s third-party-fact checking partnership is a big factor. After adding a slew of AFP bureaus with dedicated fact-checkers to our database last month, we added many more — including Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Poland, Lebanon, Singapore, Spain, Thailand and Uruguay. We now count 22 individual AFP bureaus, all started since 2018.

Other recent additions to the database involved several established fact-checkers, including PesaCheck, which launched in Kenya in 2016. Since then it’s added bureaus in Tanzania in 2017 and Uganda in 2018 — both of which are now in our database. We added Da Begad, a volunteer effort based in Egypt that has focused on social media hoaxes and misinformation since 2013. And there’s a relative newcomer too: Re:Check, a Latvian project that’s affiliated with a non-profit investigative center called Re:Baltica. It launched over the summer.

Peru’s OjoBiónico is back on our active list. It resumed fact-checking last year after a two-year hiatus. OjoBiónico is a section of OjoPúblico, a digital news service that focuses on an investigative reporting service.

We already have other fact-checkers we plan to add to our database over the coming weeks. If there’s a fact-checker you know about that we need to update or add to our map, please contact Joel Luther at the Reporters’ Lab.

Comments closed

Globally, the largest growth came in Asia, which went from 22 to 35 outlets in the past year. Nine of the 27 fact-checking outlets that launched since the start of 2018 were in Asia, including six in India. Latin American fact-checking also saw a growth spurt in that same period, with two new outlets in Costa Rica, and others in Mexico, Panama and Venezuela.

Globally, the largest growth came in Asia, which went from 22 to 35 outlets in the past year. Nine of the 27 fact-checking outlets that launched since the start of 2018 were in Asia, including six in India. Latin American fact-checking also saw a growth spurt in that same period, with two new outlets in Costa Rica, and others in Mexico, Panama and Venezuela.

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster