The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Facebook Journalism Project and the Craig Newmark Foundation are awarding grants to the Duke University Reporters’ Lab for a $1.2 million project to automate fact-checking.

The Duke Tech & Check Cooperative will bring together teams from universities and the Internet Archive to develop new ways to automate fact-checking and broaden the audience for this important new form of journalism.

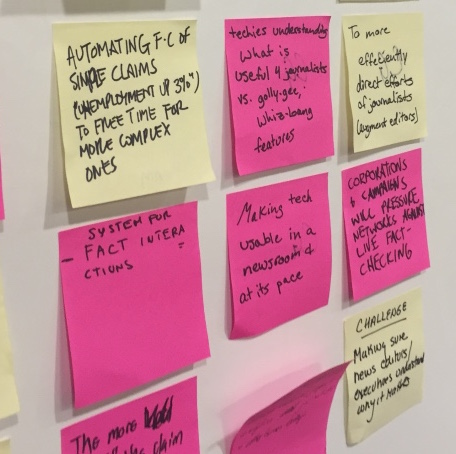

During the two-year project, computer scientists and journalism faculty from Duke, the University of Texas at Arlington and Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo will build a variety of new tools and apps. Some will help journalists with time-consuming reporting tasks, such as mining transcripts, media streams and social feeds for the most important factual claims. Others will provide instant pop-up fact-checking during live events.

The Reporters’ Lab will also coordinate and share its automation efforts with journalists and computer scientists across the country and around the world. The Tech & Check Cooperative will connect the leaders of similar projects through its relationships with the International Fact-Checking Network, the global association of fact-checkers, and awardees of Knight Prototype Fund grants to address misinformation. The Lab will host an annual meeting and will hold regular video conferences.

Knight has provided $800,000 for the project and the Facebook Journalism Project has contributed $200,000. The Newmark Foundation has pledged $200,000.

“A multitude of people and solutions are required to tackle the problem of misinformation in the digital age. The Reporters’ Lab is tackling the issue through an effective, multi-pronged approach, bringing together a network of journalists and technologists to build new tools that will promote the flow of accurate news, while strengthening their connections with major technology companies,” said Jennifer Preston, the vice president for journalism at Knight Foundation.

“The Duke Tech & Check Cooperative will tap into the power of technology to improve and expand fact-checking on a global scale,” said Campbell Brown, head of news partnerships at Facebook. “This important initiative will bring together some of the most respected experts in the industry along with new digital innovations to create practical and efficient tools for journalists and newsrooms.”

“News consumers like me want the truth, which requires more and better fact-checking,” said Newmark, founder of craigslist and the Craig Newmark Foundation. “The Duke University Tech & Check Cooperative will soon become a vital part of the fact-checking network, and I’m excited to work with them to help build a system of information we can trust.”

The Tech & Check Cooperative will incorporate technology and content developed in Share the Facts, a Duke Reporters’ Lab partnership with the Google News Lab and Jigsaw. Share the Facts provides a way for the world’s fact-checkers to identify their articles for search engines and apps.

“Automated fact-checking is no longer just a dream,” said Bill Adair, the Knight Professor of the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke and the leader of the Tech & Check Cooperative. “Advances in artificial intelligence will soon make it possible to provide people with real-time information about what’s true and what’s not.”

Partners in the Tech & Check Cooperative include:

● The University of Texas at Arlington, which has developed ClaimBuster, a tool that can mine lengthy transcripts for claims that fact-checkers might want to examine.

● The Internet Archive, which will help develop a “Talking Point Tracker” that will identify factual claims that are used repeatedly by politicians and pundits.

● Truth Goggles, a project created by developer Dan Schultz and the Bad Idea Factory to provide pop-up fact-checking for articles on the web.

● Digital Democracy, an initiative of the Institute for Advanced Technology and Public Policy at Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo, which will develop ways to identify factual claims from video of legislative proceedings in California.

About the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

Knight Foundation is a national foundation with strong local roots. We invest in journalism, in the arts, and in the success of cities where brothers John S. and James L. Knight once published newspapers. Our goal is to foster informed and engaged communities, which we believe are essential for a healthy democracy. For more, visit knightfoundation.org.

About Facebook

Founded in 2004, Facebook’s mission is to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together. People use Facebook to stay connected with friends and family, to discover what’s going on in the world, and to share and express what matters to them.

The Facebook Journalism Project was created in January 2017 to establish stronger ties between Facebook and the news industry. FJP focuses on three pillars: collaborative development of new products; tools and trainings for journalists; and tools and trainings for people.

About Craig Newmark

Craig Newmark is a Web pioneer, philanthropist, and leading advocate on behalf of trustworthy journalism, voting rights, veterans and military families, and other civic and social justice causes. In 2017, he became a founding funder and executive committee member of the News Integrity Initiative, administered by the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, which seeks to advance news literacy and increase trust in journalism.

About the Reporters’ Lab

The Duke Reporters’ Lab is a project of the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy at the Sanford School of Public Policy. The Lab conducts research into fact-checking and explores how automation can be used to help journalists and broaden audiences for their work.

Comments closed

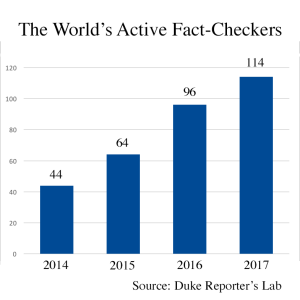

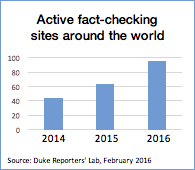

was 96.

was 96.

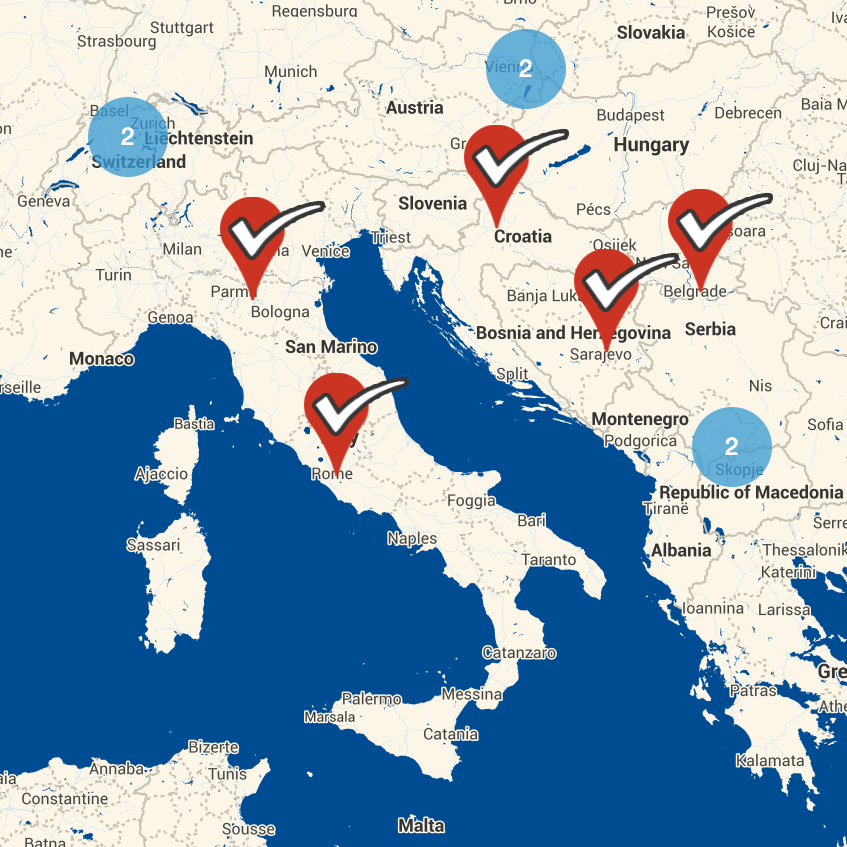

A bumper crop of new fact-checkers across the Western Hemisphere helped increase the ranks of journalists and government watchdogs who verify the accuracy of public statements and track political promises. The new sites include 14 in the United States, two in Canada as well as seven additional fact-checkers in Latin America.There also were new projects in 10 other countries, from North Africa to Central Europe to East Asia.

A bumper crop of new fact-checkers across the Western Hemisphere helped increase the ranks of journalists and government watchdogs who verify the accuracy of public statements and track political promises. The new sites include 14 in the United States, two in Canada as well as seven additional fact-checkers in Latin America.There also were new projects in 10 other countries, from North Africa to Central Europe to East Asia.