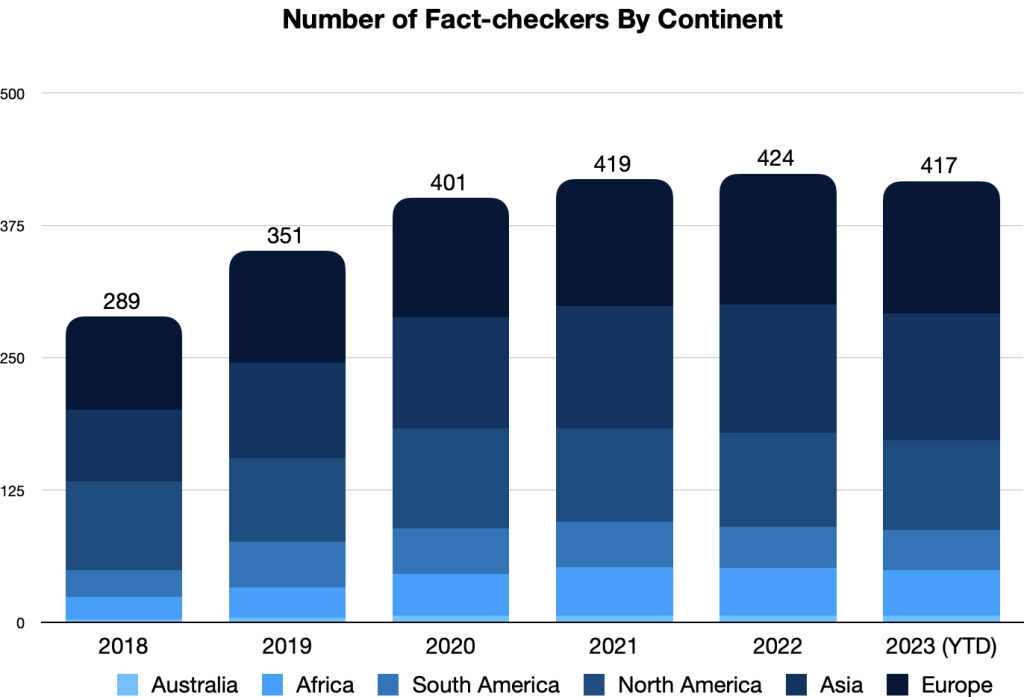

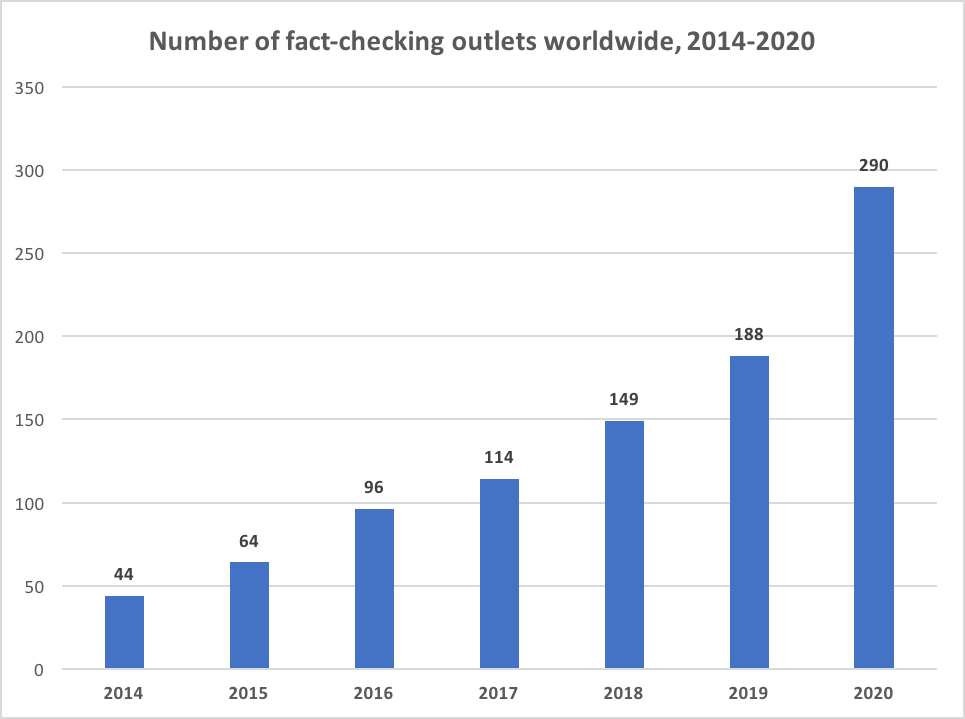

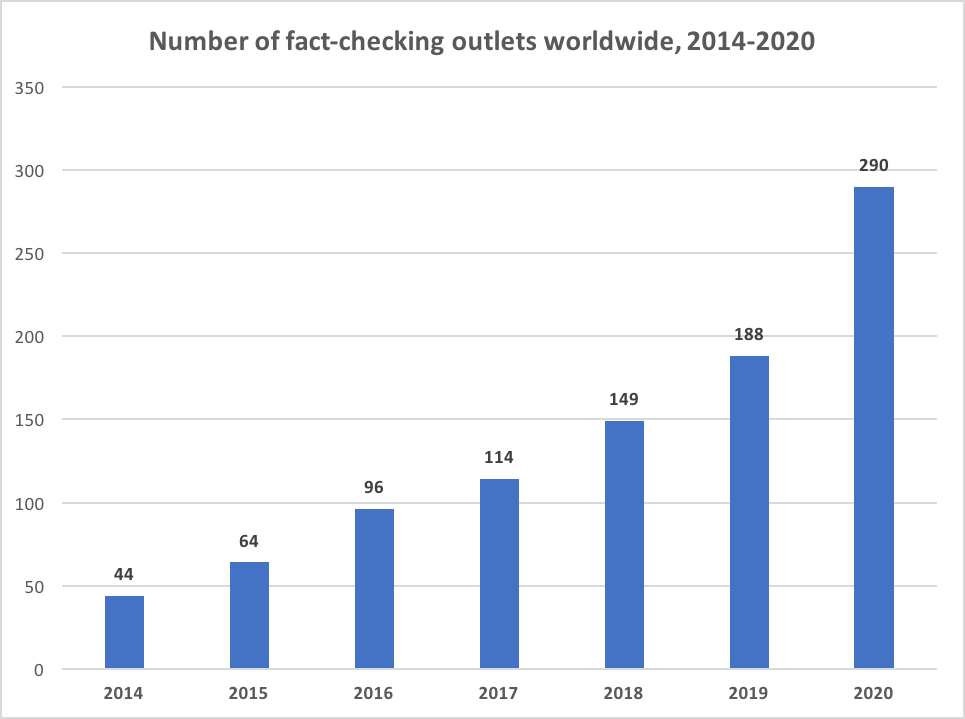

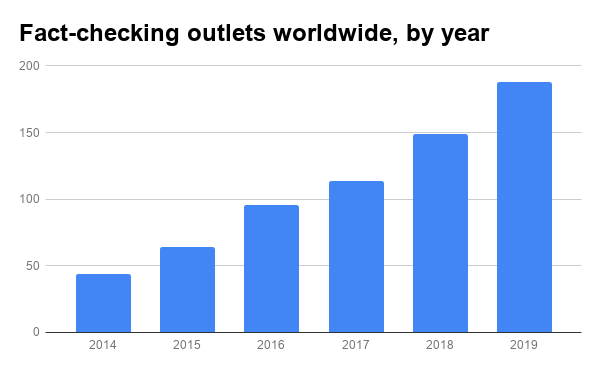

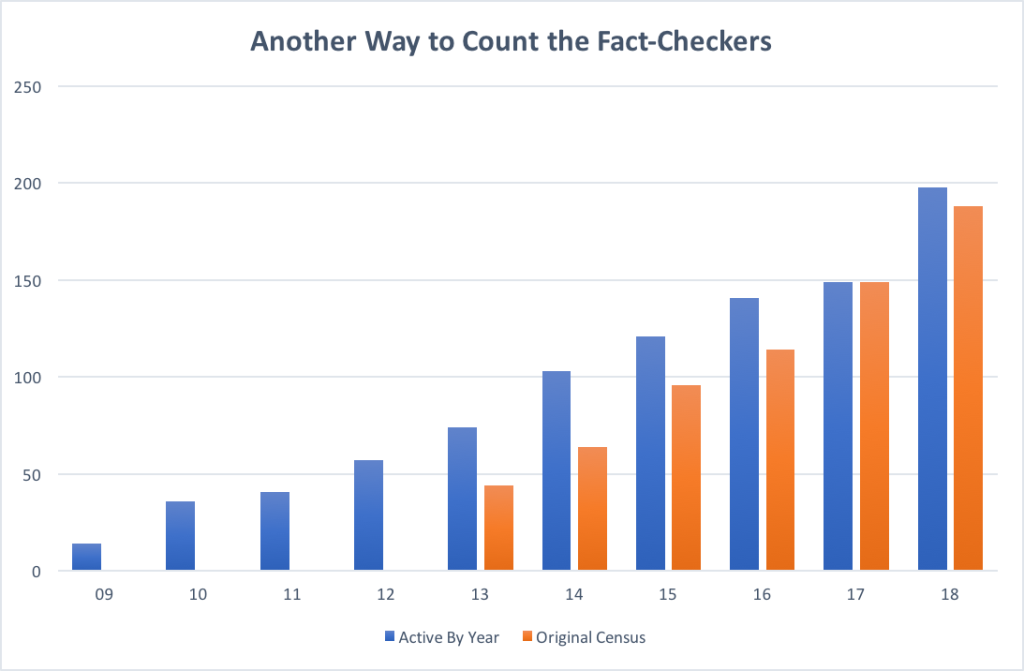

While much of the world’s news media has struggled to find solid footing in the digital age, the number of fact-checking outlets reliably rocketed upward for years — from a mere 11 sites in 2008 to 424 in 2022.

But the long strides of the past decade and a half have slowed to a more trudging pace, despite increasing concerns around the world about the impact of manipulated media, political lies and other forms of dangerous hoaxes and rumors.

In our 10th annual fact-checking census, the Duke Reporters’ Lab counts 417 fact-checkers that are active so far in 2023, verifying and debunking misinformation in more than 100 countries and 69 languages.

While the count of fact-checkers routinely fluctuates, the current number is roughly the same as it was in 2022 and 2021.

In more blunt terms: Fact-checking’s growth seems to have leveled off.

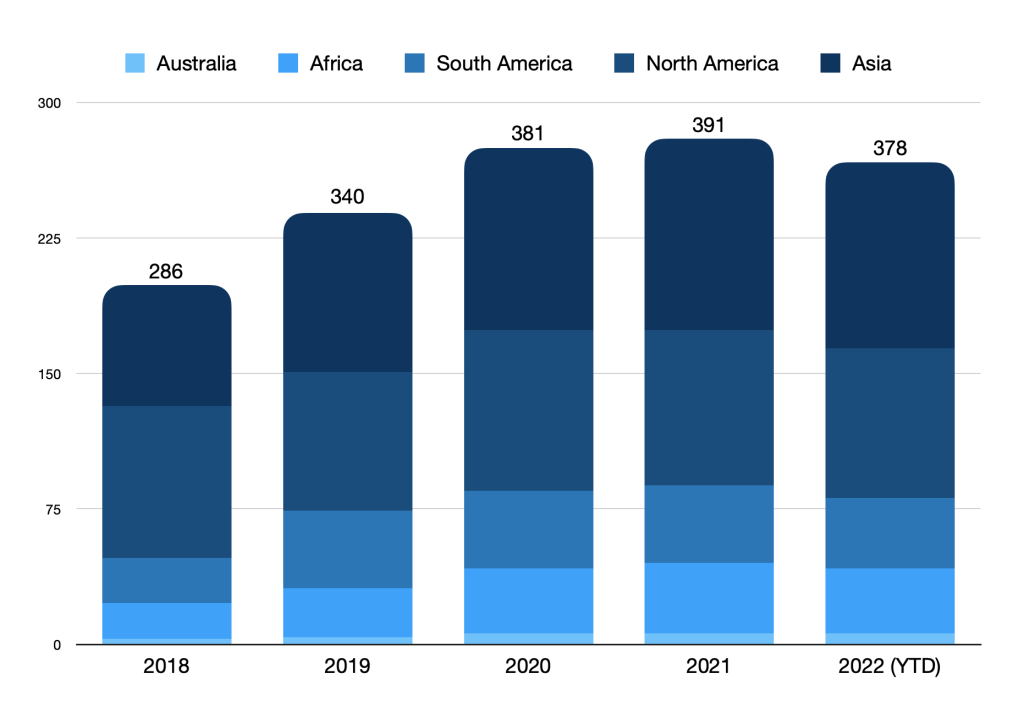

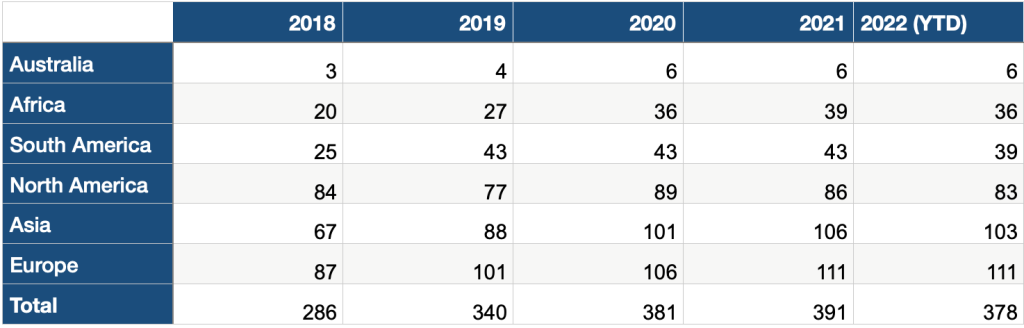

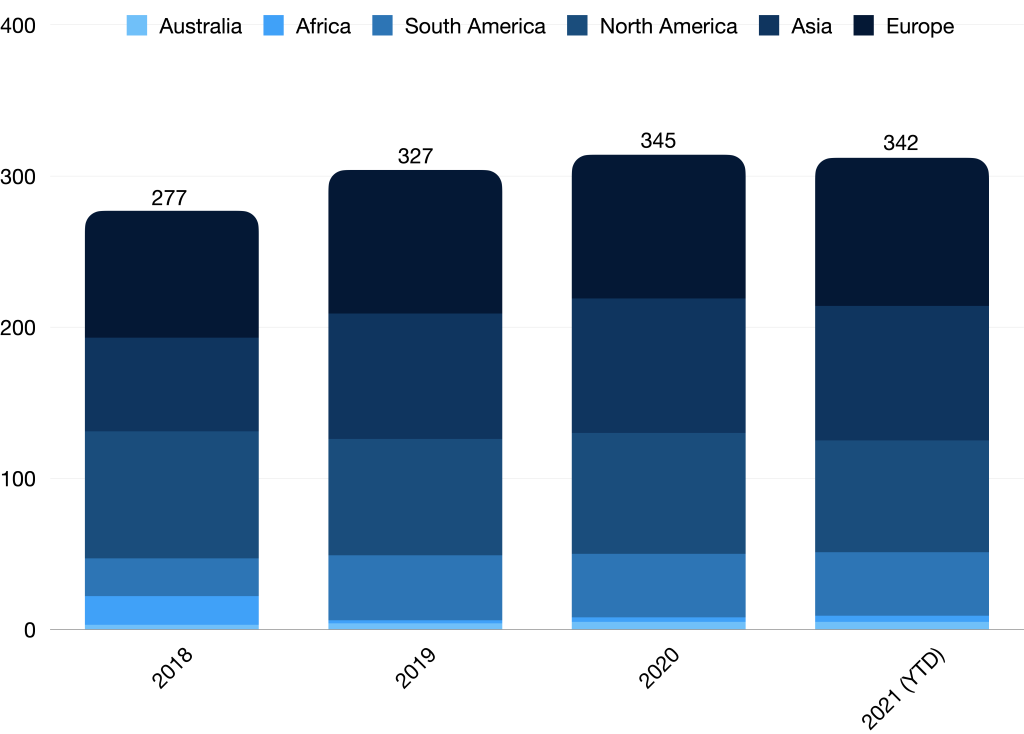

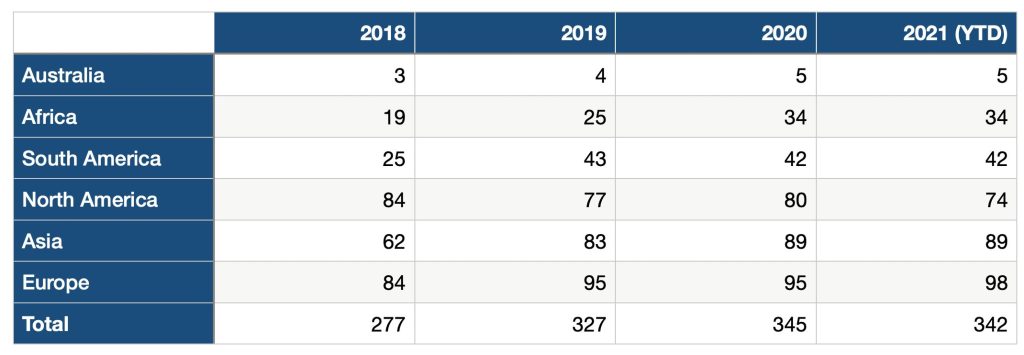

Since 2018, the number of fact-checking sites has grown by 47%. While that’s an increase of 135, it is far slower than the preceding five years, when the numbers grew more than two and a half times, or the six-fold increase over the five years before that.

There also are important regional patterns. With lingering public health issues, climate disasters, and Russia’s ongoing war with Ukraine, factual information is still hard to come by in important corners of the world.

Before 2020, there was a significant growth spurt among fact-checking projects in Africa, Asia, Europe and South America. At the same time, North American fact-checking began to slow. Since then, growth in the fact-checking movement has plateaued in most of the world.

The Long Haul

One good sign for fact-checking is the sustainability and longevity of many key players in the field. Almost half of the fact-checking organizations in the Reporters’ Lab count have been active for five years or more. And roughly 50 of them have been active for 10 years or more.

The average lifespan of an active fact-checking site is less than six years. The average lifespan of the 139 fact-checkers that are now inactive was not quite three years.

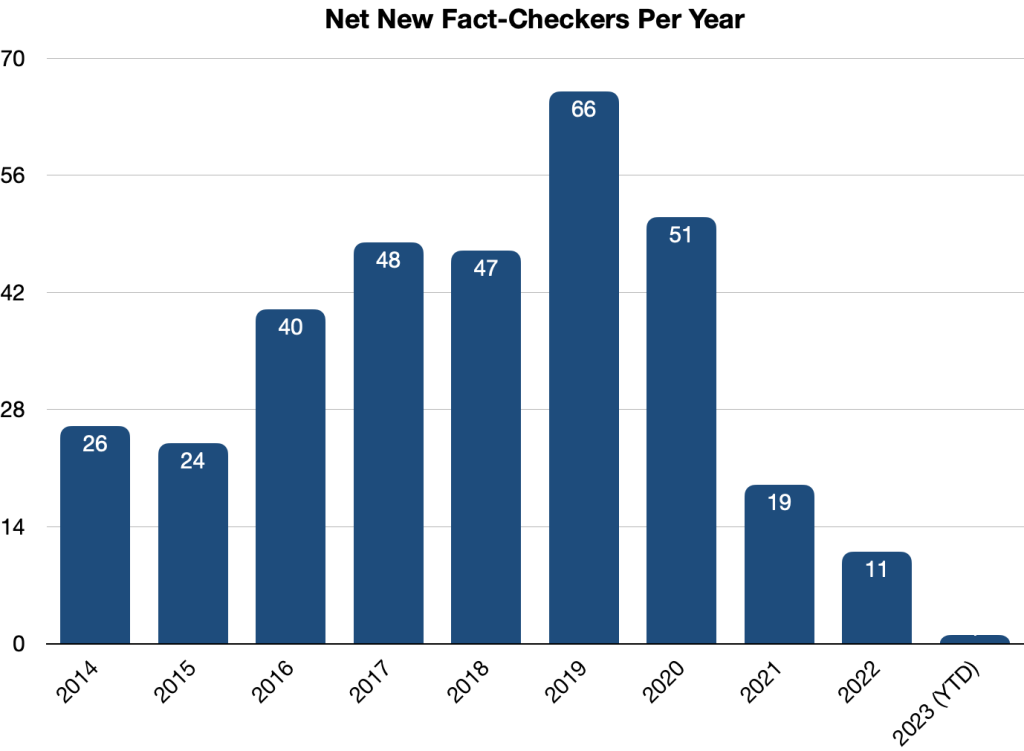

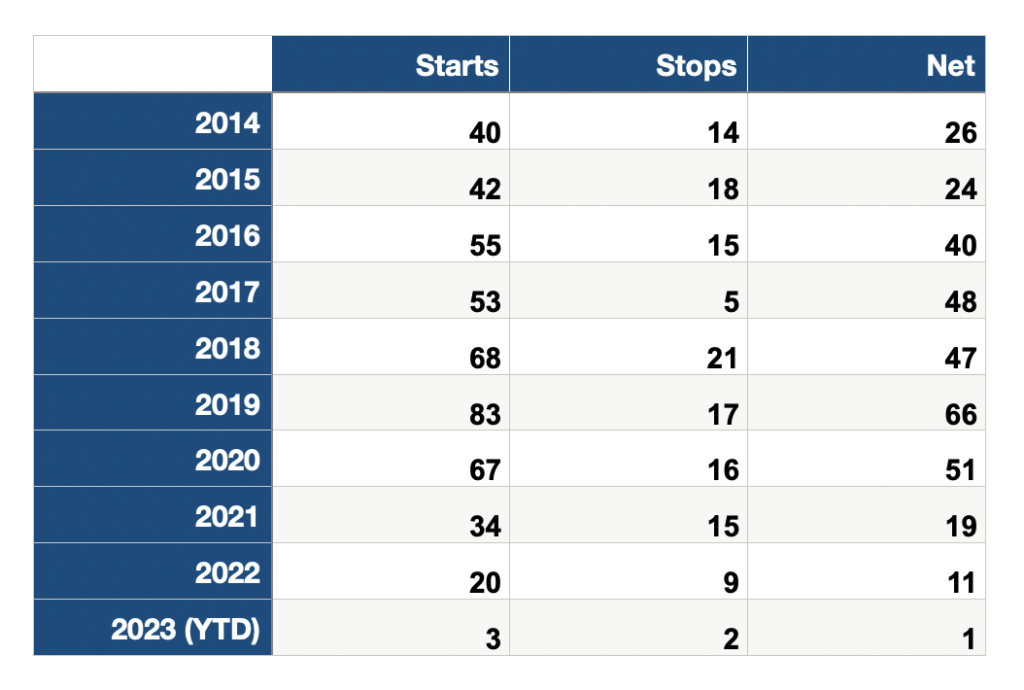

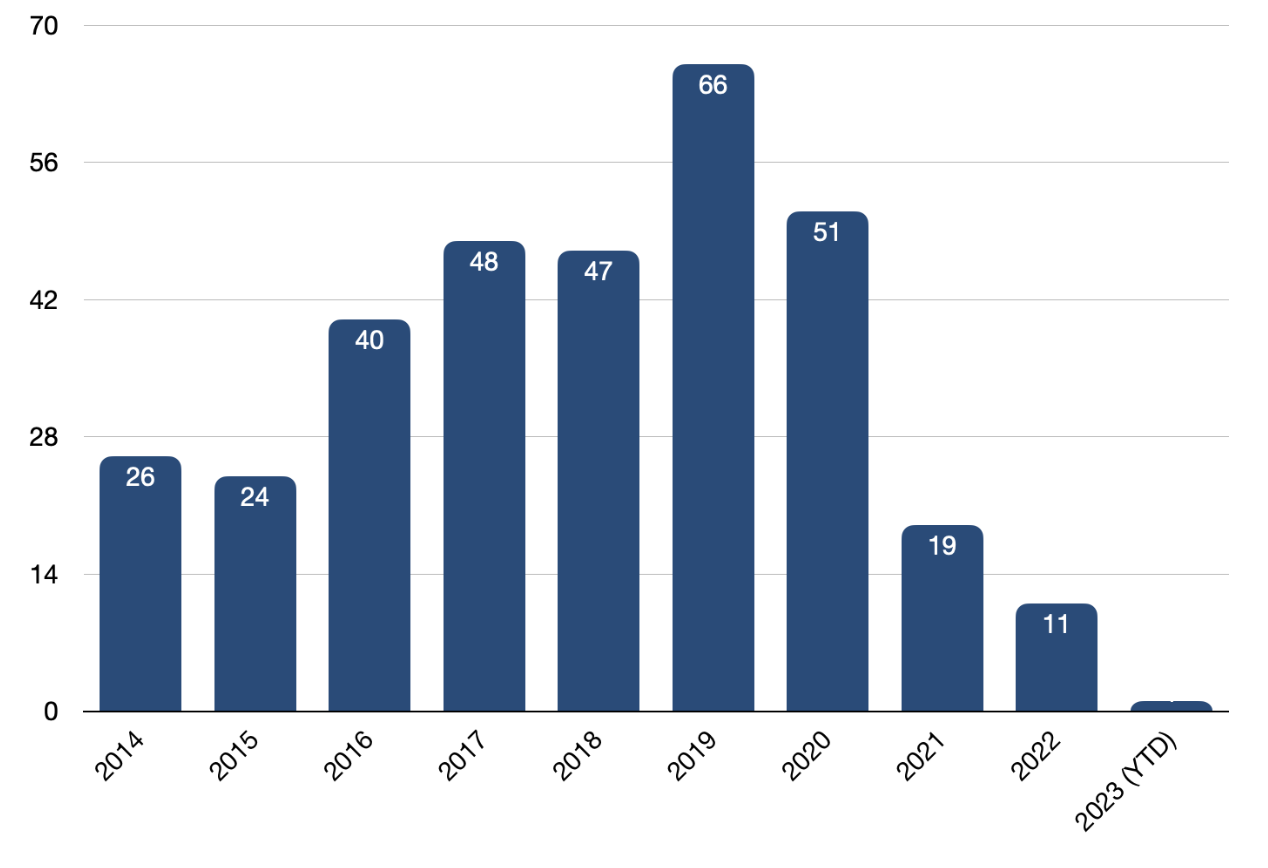

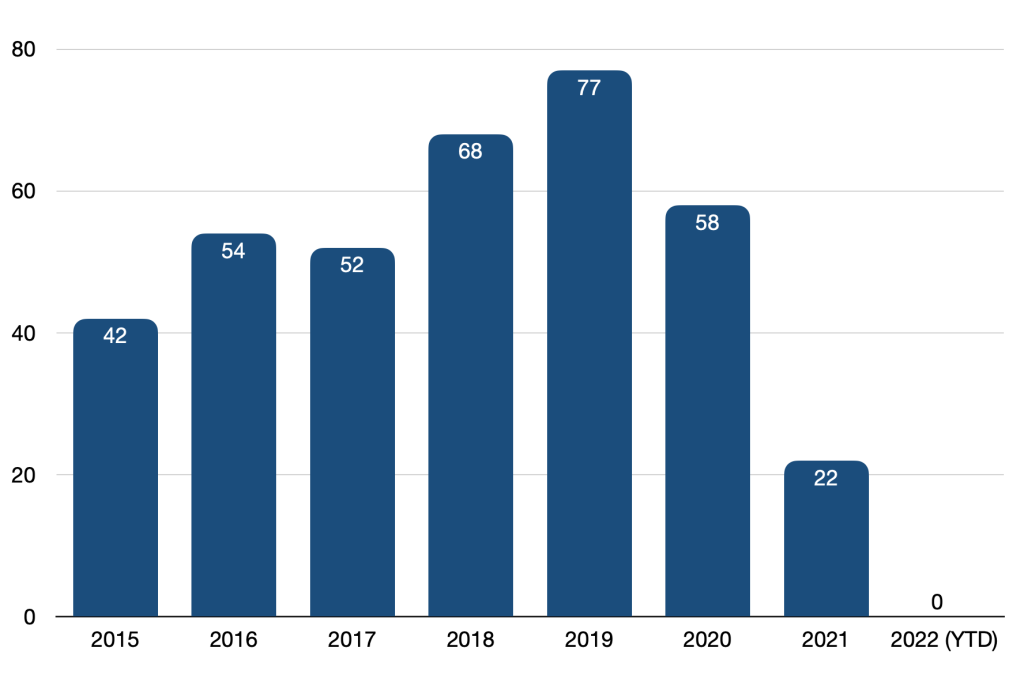

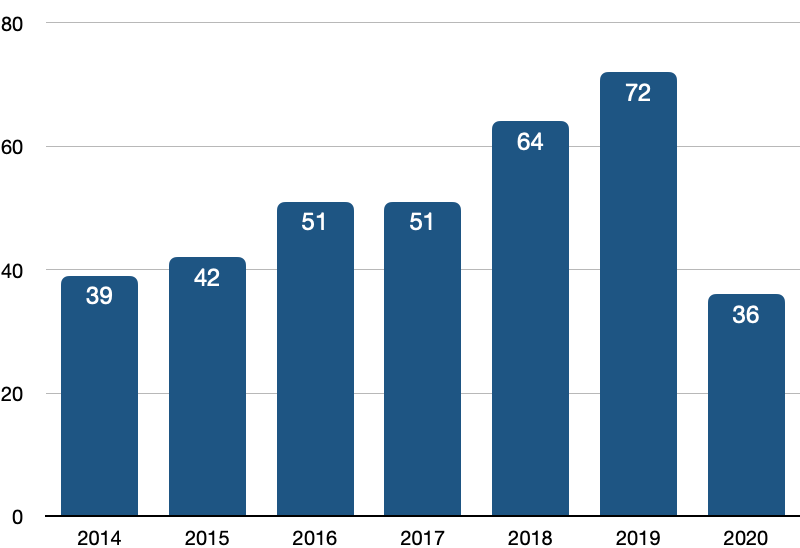

But the baby boom has ended. Since 2019, when a bumper crop of 83 fact-checkers went online, the number of new sites each year has steadily declined. The Reporters’ Lab count for 2022 is at 20, plus three additions in 2023 as of this June. That reduced the rate of growth from three years earlier by 72%.

The number of fact-checkers that closed down in that same period also declined, but not as dramatically. That means the net count of new and departing sites has gone from 66 in 2019 to 11 in 2022, plus one addition so far in 2023.

The Downshift

The Downshift

As was the case for much of the world, the pandemic period certainly contributed to the slower growth. But another reason is the widespread adoption of fact-checking by journalists and other researchers from nonpartisan think tanks and good-government groups in recent years. That has broadened the number of people doing fact-checking but created less need for news organizations dedicated to the unique form of journalism.

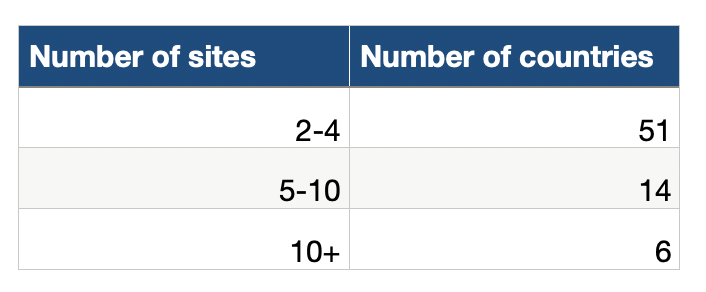

With teams working in 108 countries, just over half of the nations represented in the United Nations have at least one organization that already produces fact-checks for digital media, newspapers, TV reports or radio. So in some countries, the audience for fact-checks might be a bit saturated. As of June, there are 71 countries that have more than one fact-checker.

Another reason for the slower pace is that launching new fact-checking projects is challenging — especially in countries with repressive governments, limited press freedom and safety concerns for journalists …. In other words, places where fact-checking is most needed.

The 2023 World Press Freedom Index rates press conditions as “very serious” in 31 countries. And almost half of those countries (15 of 31) do not have any fact-checking sites. They are Bahrain, Djibouti, Eritrea, Honduras, Kuwait, Laos, Nicaragua, North Korea, Oman, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam and Yemen. The Index also includes Palestine, the status of which is contested.

Remarkably, there are 62 fact-checking services in the 16 other countries on the “very serious” list. And in eight of those countries, there is more than one site. India, which ranks 161 out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index, is home to half of those 62 sites. The other countries with more than one fact-checking organization are Bangladesh, China, Venezuela, Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt and Myanmar.

In some cases, fact-checkers from those countries must do their work from other parts of the world or hide their identities to protect themselves or their families. That typically means those journalists and researchers must work anonymously or report on a country as expats from somewhere else. Sometimes both.

At least three fact-checking teams from the Middle East take those precautions: Fact-Nameh (“The Book of Facts”), which reports on Iran from Canada; Tech 4 Peace, an Iraq-focused site that also has members who work in Canada; and Syria’s Verify-Sy, whose staff includes people who operate from Turkey and Europe.

Two other examples are elTOQUE DeFacto, a project of a Cuban news website that is legally registered in Poland; and the fact-checkers at the Belarusian Investigative Center, which is based in the Czech Republic.

In other cases, existing fact-checking organizations have also established separate operations in difficult places. The Indian sites BOOM and Fact Crescendo have set-up fact-checking services in Bangladesh, while the French news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP) has fact-checkers that report on misinformation from Hong Kong, India and Myanmar, among others.

There still are places where fact-checking is growing, and much of that has to do with organizations that have multiple outlets and bureaus — such as AFP, as noted above. The French international news service has about 50 active sites aimed at audiences in various countries and various languages.

India-based Fact Crescendo launched two new channels in 2022 — one for Thailand and another focused broadly on climate issues. Along with two other outlets the previous year, Fact Crescendo now has a total of eight sites.

The 2022 midterm elections in the United States added six new local fact-checking outlets to our global tally, all at the state level. Three of the new fact-checkers were the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, The Nevada Independent and Wisconsin Watch, all of whom used a platform called Gigafact that helped generate quick-hit “Fact Briefs” for their audiences. But the Arizona Center is no longer participating. (For more about the 2022 U.S. elections see “From Fact Deserts to Fact Streams” — a March 2023 report from the Reporters’ Lab.)

About the Reporters’ Lab and Its Census

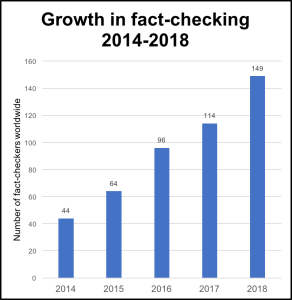

The Duke Reporters’ Lab began tracking the international fact-checking community in 2014, when director Bill Adair organized a group of about 50 people who gathered in London for what became the first Global Fact meeting. Subsequent Global Facts led to the creation of the International Fact-Checking Network and its Code of Principles.

The Reporters’ Lab and the IFCN use similar criteria to keep track of fact-checkers, but use somewhat different methods and metrics. Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database and census reports. If you have questions, updates or additions, please contact Mark Stencel, Erica Ryan or Joel Luther.

* * *

Related links: Previous fact-checking census reports

April 2014: https://reporterslab.org/duke-study-finds-fact-checking-growing-around-the-world/

January 2015: https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking-census-finds-growth-around-world/

February 2016: https://reporterslab.org/global-fact-checking-up-50-percent/

February 2017: https://reporterslab.org/international-fact-checking-gains-ground/

February 2018: https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking-triples-over-four-years/

June 2019: https://reporterslab.org/number-of-fact-checking-outlets-surges-to-188-in-more-than-60-countries/

June 2020: https://reporterslab.org/annual-census-finds-nearly-300-fact-checking-projects-around-the-world/

June 2021: https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking-census-shows-slower-growth/

Comments closed

Globally, the largest growth came in Asia, which went from 22 to 35 outlets in the past year. Nine of the 27 fact-checking outlets that launched since the start of 2018 were in Asia, including six in India. Latin American fact-checking also saw a growth spurt in that same period, with two new outlets in Costa Rica, and others in Mexico, Panama and Venezuela.

Globally, the largest growth came in Asia, which went from 22 to 35 outlets in the past year. Nine of the 27 fact-checking outlets that launched since the start of 2018 were in Asia, including six in India. Latin American fact-checking also saw a growth spurt in that same period, with two new outlets in Costa Rica, and others in Mexico, Panama and Venezuela.

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster