By the numbers:

- The Duke Reporters’ Lab counts 443 active fact-checking projects around the world in 2025, down about 2 percent so far from last year. However, the number of projects has remained largely consistent in recent years, hovering around 450.

- The slight decline comes as social media giant Meta, which partners with fact-checkers to issue independent rulings on misinformation, ended that program in the U.S.

- The volume of fact-check articles this year decreased by about 6 percent compared with 2024, based on our tally of ClaimReview, a tagging system used by many fact-checking organizations.

- Fact-checkers are still active in 116 countries and in more than 70 languages. Nearly 80 fact-checking projects operate in countries judged particularly dangerous for journalism by Reporters Without Borders.

- Even in the U.S., where Meta has stopped its partnerships, new fact-checkers continue to spring up. One nationwide effort has signed up three new local newsrooms this year and has plans for four more in the near future.

After years of weeding through the ever-growing tangle of misinformation, journalists and researchers who call out falsehoods were dealt a blow in 2025 that could reshape the landscape of fact-checking around the world.

In January, just before President Donald Trump was inaugurated for a second time, Meta announced an end to its fact-checking program in the U.S., which paid professionals to issue independent rulings on potential misinformation posted on its platforms, including Facebook and Instagram. Fact-checkers around the world feared the move could lead to similar cutbacks elsewhere.

But despite the fallout of the U.S. decision, which has created a difficult environment for raising money from foundations and other big donors, there has yet to be a dramatic decline. In its annual census, the Duke Reporters’ Lab counts 443 active fact-checking projects, down about 2 percent so far from the 451 active at the end of 2024. And new projects on the horizon, including newsrooms slated to join the Gigafact fact-checking effort in the U.S., could nudge the final count upward for the year.

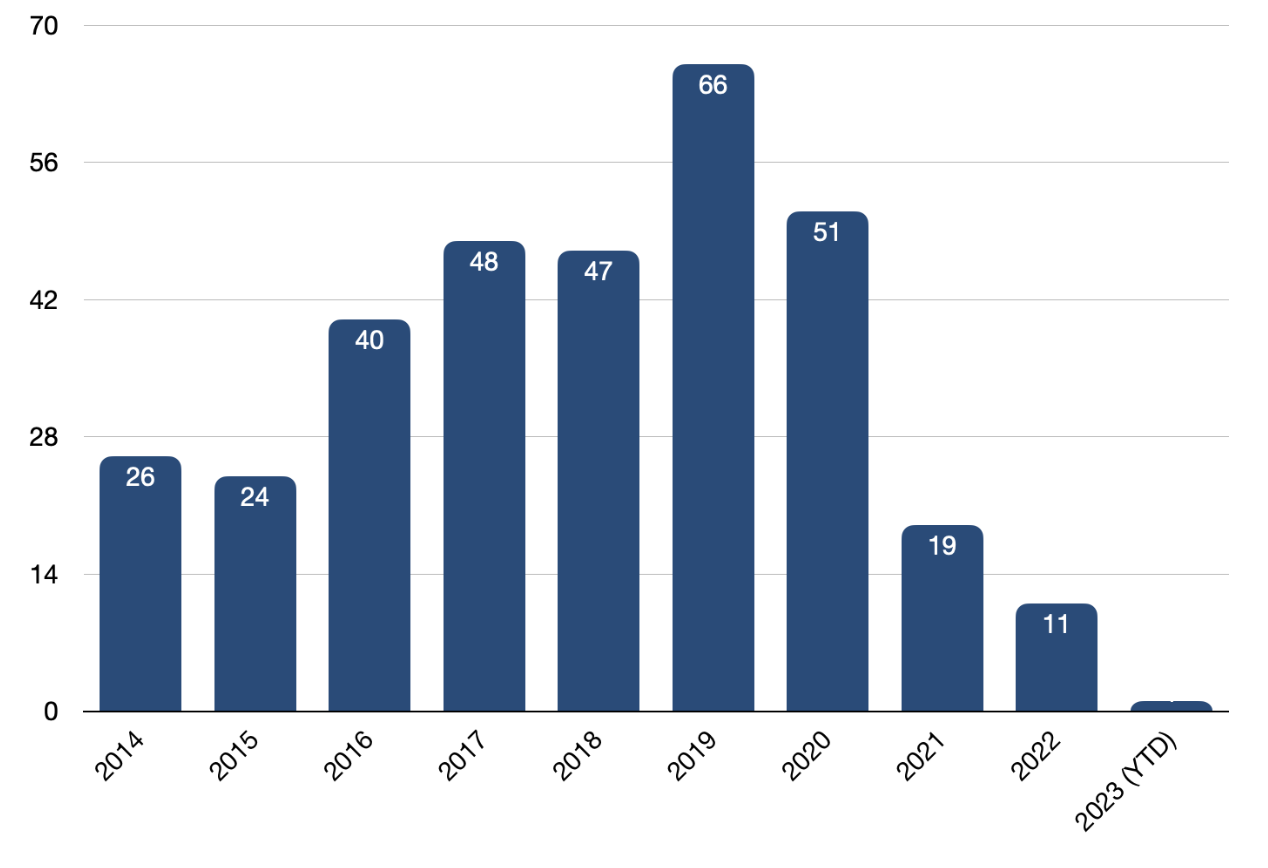

Overall, the net number of fact-checking projects around the globe has remained largely consistent in recent years, even as social media platforms have shifted toward less content moderation in the wake of billionaire Elon Musk acquiring Twitter in 2022.

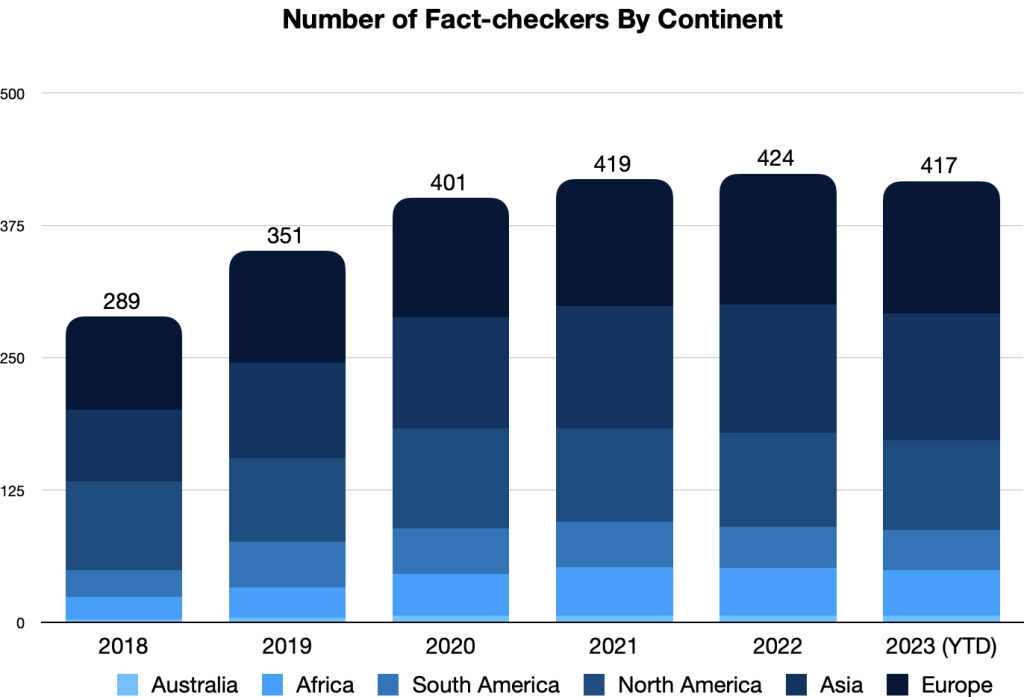

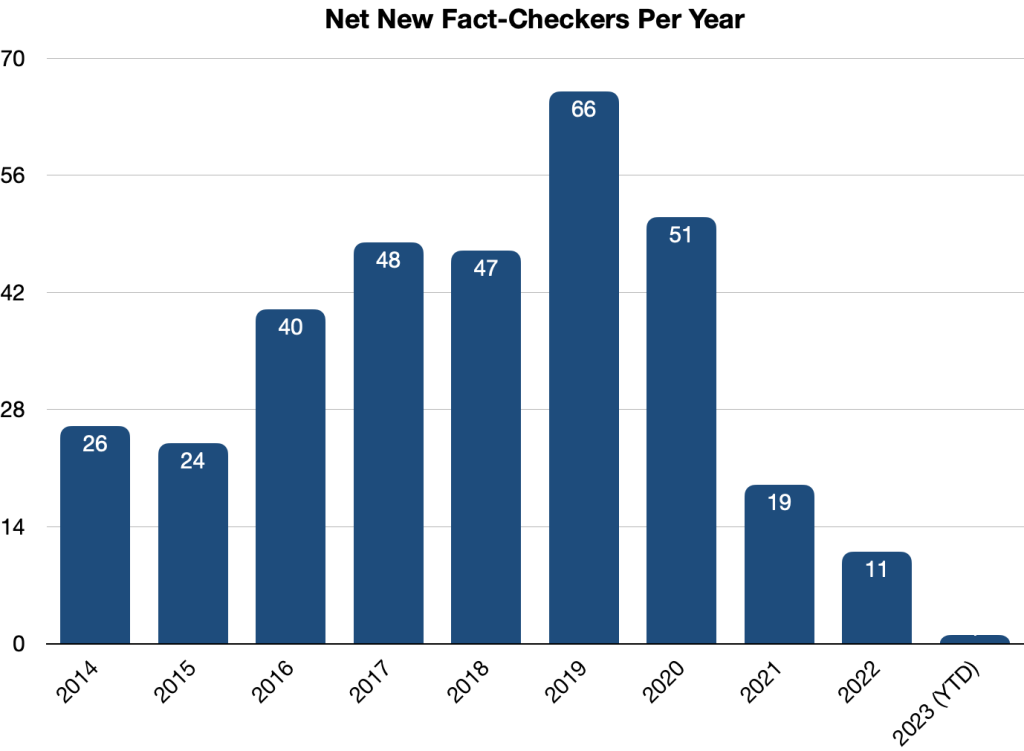

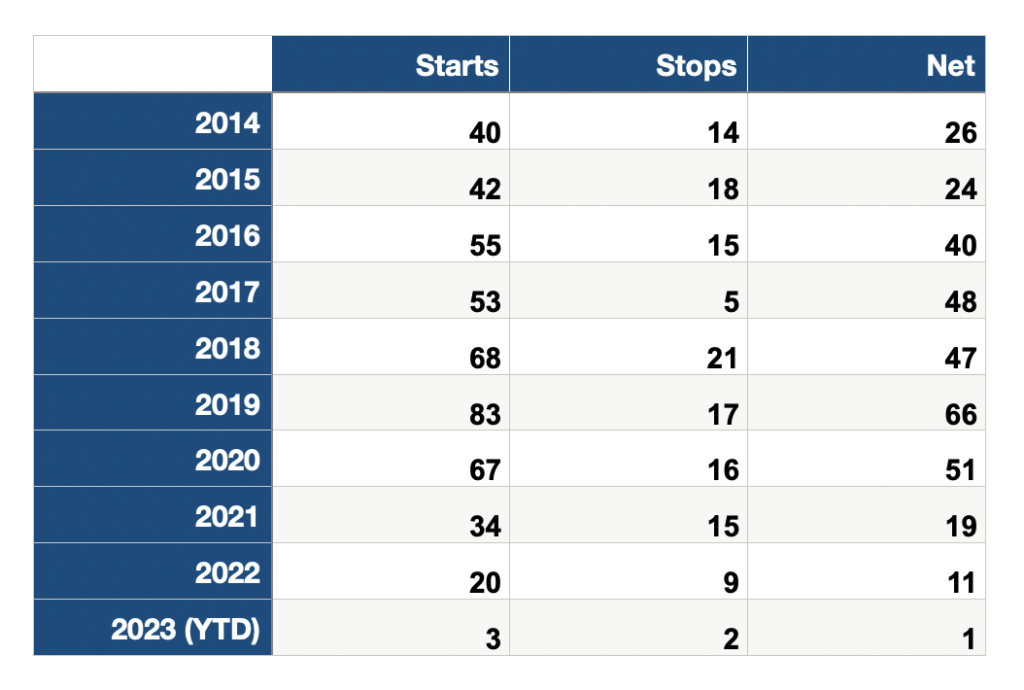

As happens every year, they come and go. In 2024, 13 projects got their start and 13 ended, making a net of zero, and in 2023, 17 opened their doors and 19 closed, a decrease of 2.

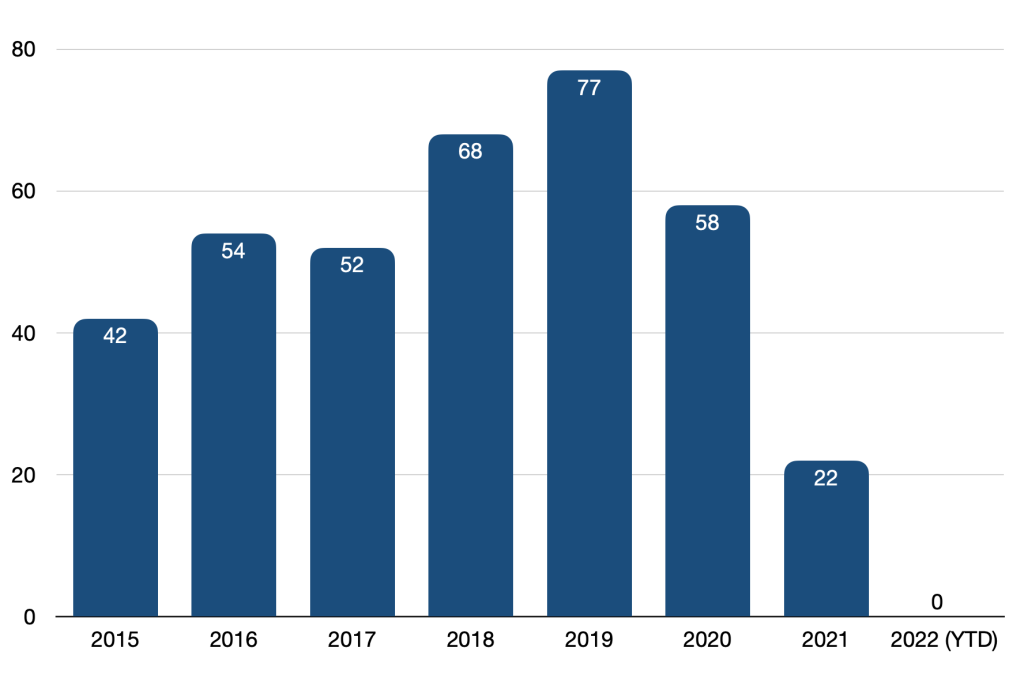

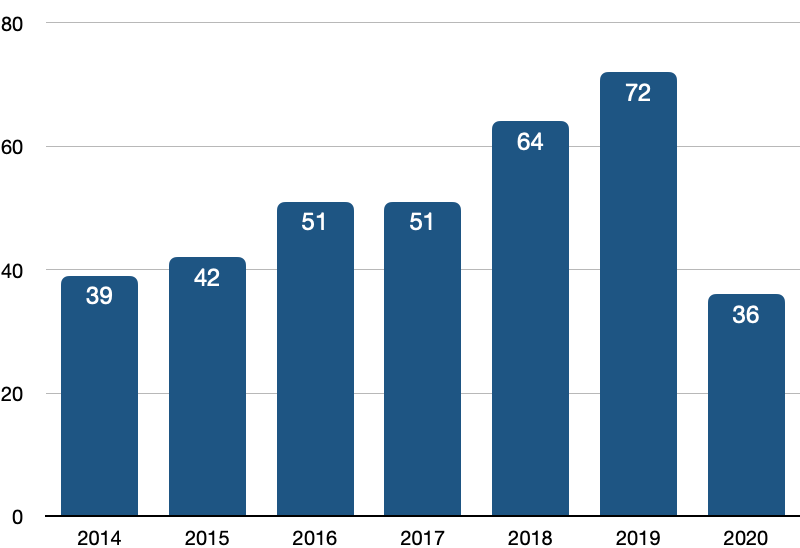

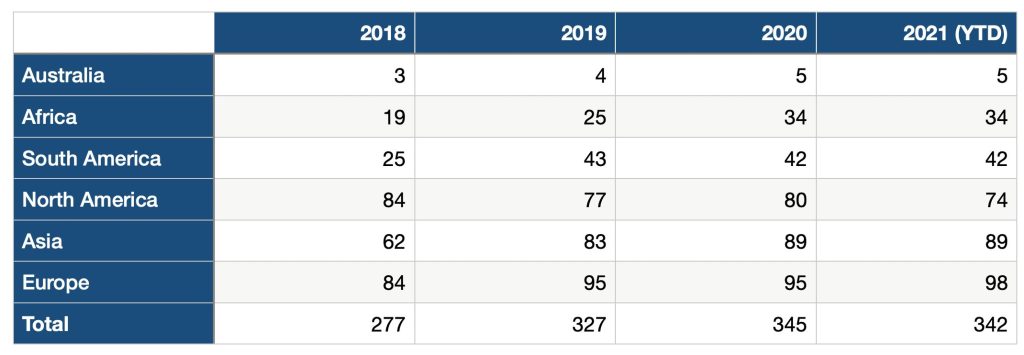

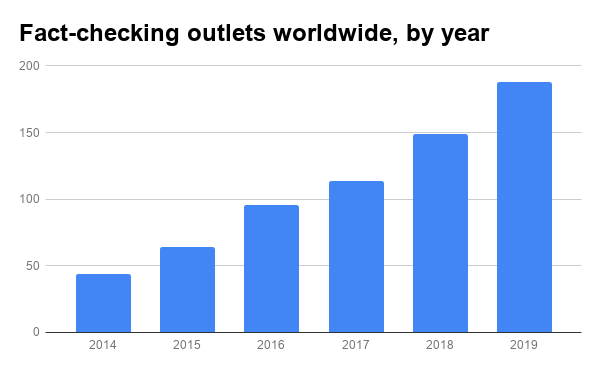

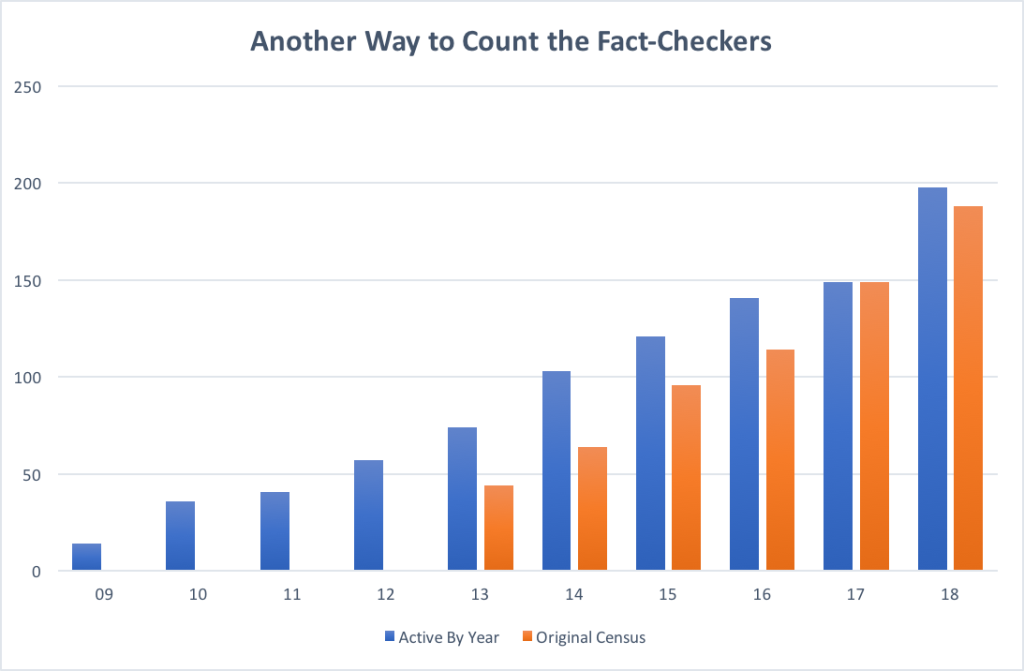

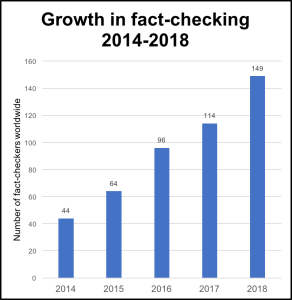

Still, the boom years seem to be over. The relative stability in the overall number of projects follows many years of massive growth in the industry. When the Reporters’ Lab first started tracking more than a decade ago, each year brought dozens of new fact-checkers, with the total number of projects shooting up from 110 in 2014 to 453 by the end of 2022, an increase of more than 300 percent.

But so far in 2025, fact-checking has seen a slight decline.

In February, the American broadcast group Tegna ended its centralized VERIFY initiative, putting a message on its website directing users to visit their local Tegna stations for VERIFY content. In April, conservative publication The Daily Caller also stopped updating its Check Your Fact initiative.

But another well-known conservative site, The Dispatch, vowed to continue, despite the end to Meta’s fact-checking program in the U.S.

“[We] did not get into the fact-checking business because of Meta’s program, or because we thought it would make us a lot of money. We got into the fact-checking business because we think it’s important,” wrote CEO and editor Steve Hayes. “…We’re not under any illusion that our decision to continue our fact-checking operation is going to save American democracy or the journalism industry. But we’re going to keep doing it because the truth matters, even if some of the loudest and most powerful voices in politics, business, and media are trying to tell you it doesn’t.”

The slight decline in fact-checking so far in 2025 is also reflected in the number of articles being produced. In the first five months of 2024, about 40,500 articles were tagged with ClaimReview, a system to identify fact-checks in search results and apps that is used by many of the world’s fact-checking organizations. During that same period this year, that number was down to about 38,000.

The future of funding

Meta’s decision to end its third-party fact-checking program in the U.S. (and replace it with a user-driven system like X’s Community Notes) has sparked concerns that the company would do the same thing in the rest of the world.

That would have a devastating impact on fact-checking organizations that have become reliant on the company for financial support. Nearly 160 projects from our count were listed as participating in Meta’s fact-checking program in early 2025 — about a third of the active projects around the world.

The percentage was higher among signatories to the International Fact-Checking Network’s Code of Principles, which holds fact-checkers to standards of nonpartisanship and transparency.

In an IFCN survey released in March, almost two-thirds of respondents reported participating, and on average, those organizations reported receiving about 45 percent of their revenue from Meta last year.

Forging ahead

Overall, our numbers show fact-checkers remain active in 116 countries and more than 70 languages.

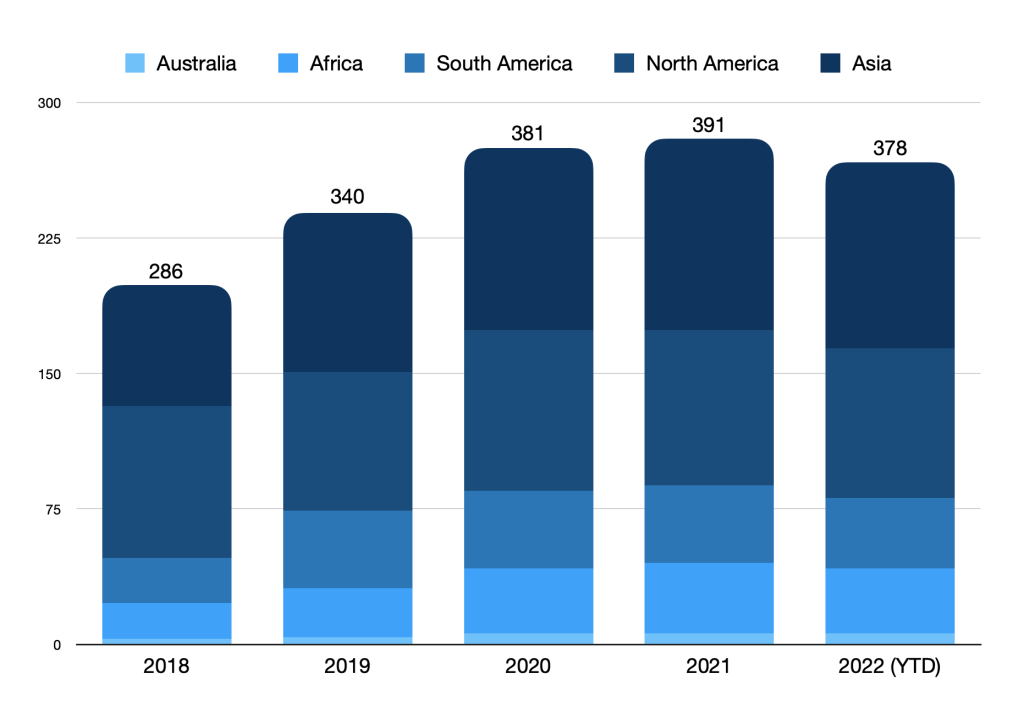

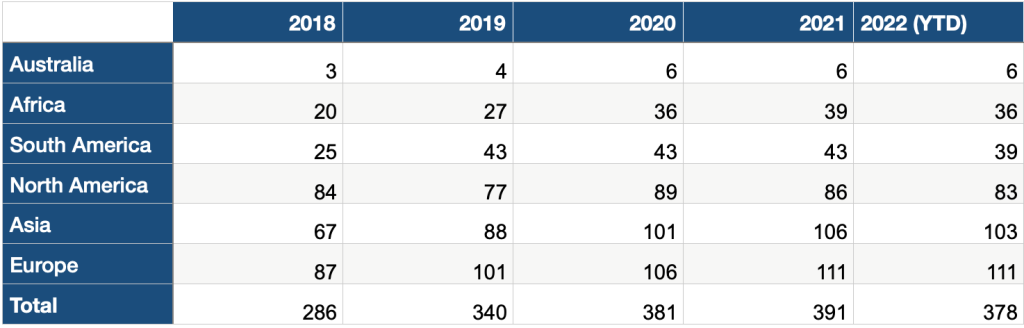

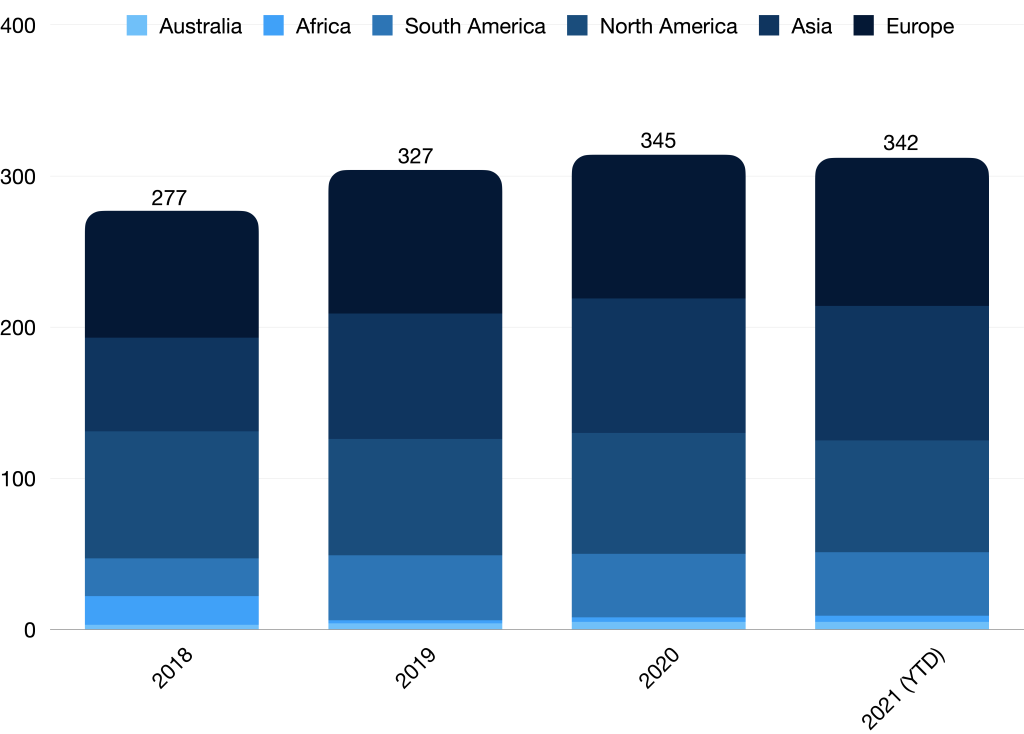

While Asia has seen slight declines each year since 2022, the number of projects continued to inch up for longer in Europe, which had an increase from 131 at the end of 2022 to 139 by the end of 2024. The number of projects held almost steady during that time frame in Africa (with 66-67 projects) and South America (with 38-39).

Many fact-checkers are continuing to do their work in hostile environments.

About 80 of the world’s active fact-checking organizations operate in countries that have been judged by Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index to be particularly dangerous for practicing journalism. Those places include India, Hong Kong, Bangladesh and Egypt, all of which have multiple fact-checking projects. There are also lone fact-checking outposts in countries like Iran, Cuba, Saudi Arabia and Cambodia.

And even though Meta has backed away from funding fact-checking in the U.S., new operations continue to spring up.

Three newsrooms — Maine Trust for Local News, South Dakota News Watch and Suncoast Searchlight in Florida — have all begun participating this year in the Gigafact project, an effort that helps local journalists produce bite-sized “fact briefs” that give yes or no answers about factual claims.

That brings Gigafact’s network to more than a dozen newsrooms across the country — and it expects to add four more local news organizations to its roster in June.

About the Reporters’ Lab and its Census

The Duke Reporters’ Lab began tracking the international fact-checking community in 2014, when director Bill Adair organized a group of about 50 people who gathered in London for what became the first Global Fact meeting. Subsequent Global Facts led to the creation of the International Fact-Checking Network and its Code of Principles.

The Reporters’ Lab and the IFCN use similar criteria to keep track of fact-checkers, but use somewhat different methods and metrics. Here’s how we decide which fact-checkers to include in the Reporters’ Lab database and census reports. If you have questions, updates or additions, please contact Erica Ryan.

Previous Fact-Checking Census Reports

Note: The Reporters’ Lab regularly updates our counts as we identify and add new sites to our fact-checking database. As a result, numbers from earlier census reports differ from year to year.

- April 2014

- January 2015

- February 2016

- February 2017

- February 2018

- June 2019

- June 2020

- June 2021

- June 2022

- June 2023

- June 2024

The Downshift

The Downshift

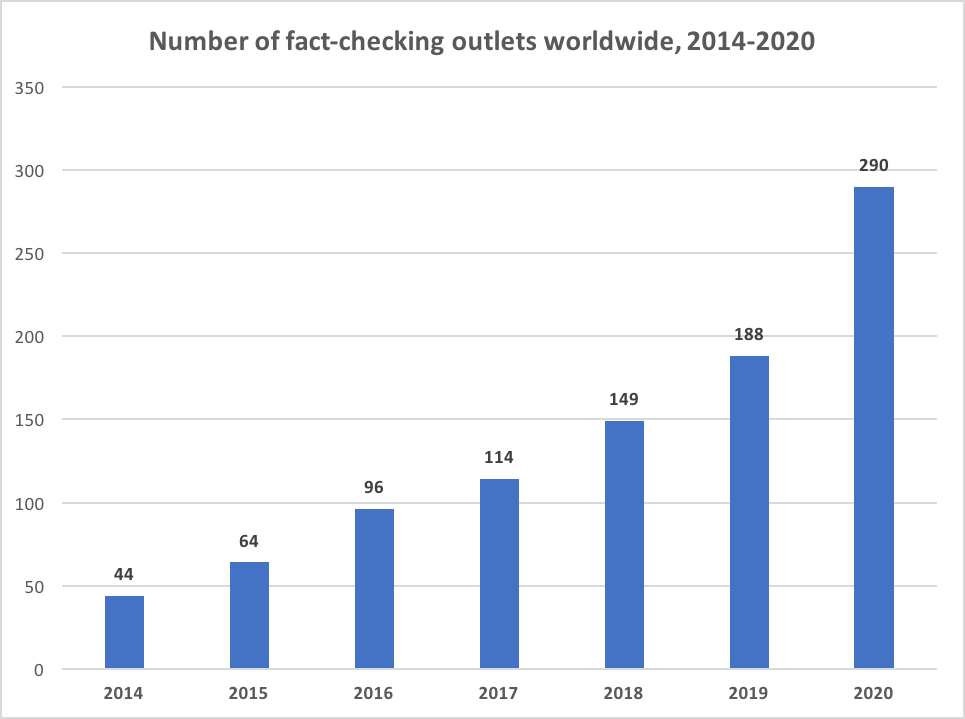

Globally, the largest growth came in Asia, which went from 22 to 35 outlets in the past year. Nine of the 27 fact-checking outlets that launched since the start of 2018 were in Asia, including six in India. Latin American fact-checking also saw a growth spurt in that same period, with two new outlets in Costa Rica, and others in Mexico, Panama and Venezuela.

Globally, the largest growth came in Asia, which went from 22 to 35 outlets in the past year. Nine of the 27 fact-checking outlets that launched since the start of 2018 were in Asia, including six in India. Latin American fact-checking also saw a growth spurt in that same period, with two new outlets in Costa Rica, and others in Mexico, Panama and Venezuela.

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster

And that list of startups does not count one short-run fact-checking project — a TV series produced by public broadcaster